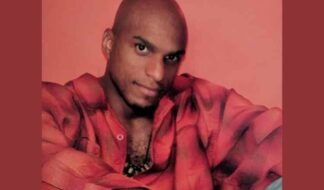

OLIVER "BILLY" SIPPLE. Born, Detroit, Nov. 20, 1941. Died, San Francisco, Feb. 2, 1989. A reluctant hero, he strolled into history at a precise psychological moment but an inconvenient time. His year with destiny: 1975.

Billy's favorite San Francisco gay bar was the New Belle Saloon. Following his death (30 friends attended his funeral), the establishment displayed a framed White House letter: "Mrs. Ford and I express our deepest sympathy in this time of your friend's passing. President Gerald Ford."

It was not the thank-you note Billy had originally received. That treasured item – succinct, but surely just as sincere – cited him for saving the 62-year-old president's life, Sept. 22, 1975. On that eventful day the Vietnam ex-Marine – living on a disability pension, exiting a VA Hospital – joined an expectant crowd of 3,000 gathered at the elegant Saint Francis Hotel.

By chance Billy stood next to a fade-in, fade-out, gray drab of a woman in a blue raincoat. Her name, Sara Jane Moore. She watched transfixed as President Ford, leaving the hotel, waved to bystanders, and headed toward the black-metallic presidential limousine, carelessly guarded by Secret Service agents.

Without a finger's snap of hesitation, Sara Jane lunged forward, flashed a steel-silver 38-caliber pistol, squeezed its eager trigger, as Billy, with instantaneous response, grabbed her wrist. The bullet veered five feet wide of its living-breathing target.

Salvation for one. Instant notoriety for two. Sipple urged the San Francisco police not to release his name or his Marine identity. The police were baffled. But it was too late for a vanishing act. Billy was a televised national hero. Unknown to the authorities he was also a closeted homosexual.

Ten years earlier Billy had been Harvey Milk's boyfriend. He now feared publicity. And perhaps understandably so. This was three years before "Come out, come out, wherever you are" Milk was elected San Francisco supervisor. (And assassinated with Mayor Dan Mascone in 1978.)

It was Milk who told San Francisco Chronicle gossip mavin Herb Caen "Billy's gay. Maybe this will help break the stereotype." Six local papers zeroed in. Gay liberation groups petitioned for a hero's official recognition. Instead, Billy became alienated from his Baptist mother, his family, service vets and organizations. (He and mom reconciled later.)

"My sexual orientation has nothing to do with saving Ford's life," he told reporters before bringing a lawsuit for $15 million against seven San Francisco newspapers for privacy invasion. The case was thrown out. Ruling: Sipple's act of heroism made him a public figure; thus, "fair game."

The strain was too much. Billy's mental and physical health imploded over the years. He drank excessively, became depressed, toxic, suicidal. He lived on $400 a month in a cheap Tenderloin District room. On the day he died, he told a buddy he had been turned away from the VA hospital. He had pneumonia.

In 2001, Detroit News columnist Deb Price interviewed former President Ford. He answered reader's allegations that he had deliberately, carefully distanced himself from Sipple. "As far as I was concerned, I had done the right thing and the matter was ended. I didn't learn until sometime later he was gay. I don't know where anyone got the crazy idea I was prejudiced and wanted to exclude gays."

In the recent reverential, visibly touching, national mourning, media coverage of President Gerald R. Ford's funeral there was no mention of once-heroic, fellow Michigander Oliver "Billy" Sipple. And who indeed remembers Billy these days anyway?

Lest we forget: Don't Ask. Do Tell.

Topics:

Opinions