By Jack Veasey

Exclusively for Between The Lines

National Gay History Project

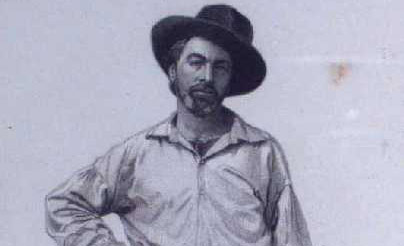

Walt Whitman (1819-92) was the father of both American poetry and modern poetry in general. His monumental collection of poems, "Leaves of Grass," established free verse as the international norm for poetry in English – and celebrated gay sexuality with surprising openness for its time in its remarkable series of "Calamus Poems," named for a phallic root with an aphrodisiac reputation.

Largely self-educated – he attended public schools up to age 11, when he started to contribute to his family's support with work as an office boy – Whitman loved young working-class men. He often sang their praises in his writing, and considered himself "one of the roughs." Though Whitman would work in journalism and government office jobs, and become well-known as a somewhat controversial published poet, his longest romantic relationship would be with Pete Doyle, a young streetcar conductor who had been a Confederate artilleryman.

But by the time he met Doyle – in 1865, toward the close of the Civil War — he had spent three years getting close to many wounded soldiers on both sides of the conflict as a volunteer in Washington military hospitals. Ultimately he would estimate that he'd made over 600 visits and "gone among from 80 to 100 thousand" sick and wounded soldiers. The experience would change his life, his outlook and his poetry dramatically.

As was not the case in previous wars, no major author served in the Civil War military, though other authors interacted with soldiers and experienced some of the conflict's events. For instance, fellow gay author Herman Melville went on scouting rides as research for his "Aspects of War." But Whitman's output of war writing – the poetry volume "Drum Taps," the prose books "Memoranda During The War" and "The Wound Dresser," his famous lecture and poems on the death of President Lincoln (including his most popular poem, "O Captain, My Captain," memorized by schoolchildren throughout the 20th century) would have unequalled impact, and identify him with the war forever.

Perhaps it was because of how personally the war touched him to begin with, and then how completely he hurled himself into the experience.

In December 1862, Whitman's younger brother George, a member of the 51st New York infantry, was wounded in the battle of Fredericksburg. Three of Walter and Louisa Whitman's seven sons were named after American leaders; George Washington Whitman was one of them. When the name "First Lieutenant G. W. Whitmore" appeared on a list of fallen and wounded soldiers in the Dec. 16 edition of the New York Tribune, Whitman feared that it referred to George. Whitman left his Brooklyn home and headed south, walking night and day, unable to get a ride, but determined to find out what had happened to his brother. His wallet was stolen by a pickpocket on the way and he arrived in Virginia penniless. Happily, Whitman found George shortly after Christmas, with only a minor facial wound, in a camp at Falmouth.

However, Whitman's relief at finding George was overshadowed by the effects of some other things he saw there. "Spent a good part of the day in a large brick mansion on the banks of the Rappahamnock, used as a hospital since the battle," he wrote. "Out doors, at the foot of a tree, within 10 yards of the front of the house, I noticed a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc., a full load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each covered with its brown woolen blanket. In the dooryard, toward the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel-staves or broken boards, stuck in the dirt."

After travelling to Washington, D.C., to accompany some wounded soldiers, Whitman began volunteering in local war hospitals. He was made an unpaid "delegate" of the Christian Commission, authorized to visit the wounded and sick and provide them with whatever comfort and assistance he could. He found he had an "instinct and facility" for this work, and was soon spending most of his time at it. He worked part-time as a clerk in the army paymaster's office to support himself, often spending his own money to buy food, writing paper and other supplies for the wounded.

Whitman would sometimes clean or dress wounds, but his presence with the men was mostly for moral support. He has been described as a "psychological nurse." He would listen to the soldier's stories or problems, hold the hand of a man in pain or delirium, keep a vigil by the bedside of the dying, write letters for those who were unable to write – even write to tell families that a soldier had passed away. Sometimes he would entertain the men by reading to them. In addition to the practical aid he offered, he was a father figure to the men. He helped POWs and deserters from the South, as well as Northern soldiers.

One result of this work was that Whitman, who always kept a handmade notebook with him, recorded one of the most vivid accounts of the war – and by far the most human account, primarily focused on how it affected individual people and their families, both North and South. The notebook entries and newspaper articles he wrote during this experience became the book "Memoranda During The War," which later became the extensive Civil War section of "Specimen Days," ultimately Whitman's volume of collected prose.

Among the many "cases" he comforted, the poet would record their poignant and wrenching stories in as much detail as he could. At one point his cases included two brothers — one Rebel soldier, one Yankee — who had both been wounded badly in the same battle and were hospitalized in adjoining wards. They hadn't seen each other in four years. Both of them ultimately died from their injuries. His description of his relationship with the Rebel soldier is typical of his writing: "Very intelligent and well bred — very affectionate — held on to my hand, and put it by his face, not wanting to let me leave … he says to me suddenly … 'I am a rebel soldier.' I said I did not know that, but it made no difference. Visiting him daily for about two weeks after that … I lov'd him much, always kiss'd him, and he did me."

His entries about the men often include confessions of his feelings for them, and his descriptions of them are sensuous and beautiful: "In one of the hospitals I find Thomas Haley, company M, 4th New York cavalry — a regular Irish boy, a fine specimen of youthful physical manliness — has not a single friend or acquaintance here — is sleeping soundly at this moment, (but it is the sleep of death) — has a bullet-hole straight through the lung … He lies there with his frame exposed above the waist, all naked, for coolness, a fine built man, the tan not yet bleach'd from his cheeks and neck. It is useless to talk to him … the poor fellow, even when awake, is like some frighten'd, shy animal. Much of the time he sleeps, or half sleeps. (Sometimes I thought he knew more than he show'd.) I often come and sit by him in perfect silence; he will breathe for 10 minutes as softly and evenly as a young babe asleep. Poor youth, so handsome, athletic, with profuse beautiful shining hair. One time as I sat looking at him while he lay asleep, he suddenly, without the least start, awaken'd, open'd his eyes, gave me a long steady look, turning his face very slightly to gaze easier – one long, clear, silent look — a slight sigh — then turn'd back and went into his doze again. Little he knew, poor death-stricken boy, the heart of the stranger that hover'd near."

No matter how sad the story, Whitman's passion for these young men surfaces regularly in his stories about them. And he recognized some of them as kindred spirits, including these two Southern escapees who sound like a couple: "Two of them, one about 17, and the other perhaps 25 or '6, I talk'd with some time. They were from North Carolina, born and rais'd there, and had folks there. The elder had been in the rebel service four years. He was first conscripted for two years. He was then kept arbitrarily in the ranks … the younger had been soldiering about a year; … there were six brothers (all the boys of the family) in the army, part of them as conscripts, part as volunteers; three had been kill'd; one had escaped about four months ago, and now this one had got away; … He and the elder one were of the same company, and escaped together — and wish'd to remain together."

Whitman and Lincoln

During the war, Whitman became powerfully enamored of President Abraham Lincoln, whom he perceived as the embodiment of the Union — and the epitome of a strong leader grounded by humble beginnings. Lincoln exemplified qualities the poet had anticipated nearly a decade before in an 1856 political tract, "The Eighteenth Presidency." Disgusted with corrupt politicians, Whitman had expressed yearning for a "Redeemer President of These States," who would be "some heroic, shrewd, fully-formed, healthy-bodied, middle-aged, beard-faced American blacksmith or boatsman" who would "walk into the Presidency … with the tan all over his face, breast, and arms."

Whitman had gotten his first look at his hero in New York in 1861, when he stood among a crowd of curious spectators as the president-elect arrived at the Astor House hotel during a stopover on his way from Illinois to Washington. Later, working as a government clerk and hospital volunteer in Washington, he would see Lincoln in passing about 30 times. "I see the president almost every day," he wrote in 1863. "We have got so that we exchange bows, and very cordial ones." After Lincoln gave him a long look one day, Whitman wrote, "He has a face like a Hoosier Michaelangelo." Whitman would write vivid descriptions of Lincoln in his notebooks and bemoan that none of the portraits done of the man did him justice; he felt only one of the great masters would be equal to the task. He was struck by Lincoln's "dark brown face, with the deep-cut lines, the eyes, always … with a deep latent sadness in the expression." Whitman's preoccupation with Lincoln's appearance has led some critics to assert that his feelings for the president "bordered on infatuation."

He was delighted to have "a railsplitter and a flat-boatsman" in the White House, but it was inner qualities he perceived in Lincoln that he admired most. He praised the president's "horse sense," noting that he was "very easy, flexible, tolerant," but also capable of "indomitable firmness." He noted in Lincoln a spiritual nature "of the amplest, deepest-rooted, loftiest kind" and summed him up as "the greatest, best, most characteristic, artistic, moral personality" in America.

Though Whitman never alluded to the president's sexuality, one can't help but wonder if that could have influenced the poet's attraction to him. Biographers since have argued about whether or not Lincoln was gay. Interestingly, some of these speculations relate to a poem written by Lincoln himself describing a marriage-like relationship between two men:

For Reuben and Charles have married two girls,

But Billy has married a boy.

The girls he had tried on every side,

But none he could get to agree;

All was in vain, he went home again,

And since that he's married to Natty.

It was another poet, Carl Sandburg, who first insinuated that Lincoln had a homoerotic relationship with his friend Joshua Fry Speed in a 1926 biography, saying their relationship had "a streak of lavender, and spots soft as May violets." Speed and Lincoln's bodyguard, Captain David Derickson, among others, have been identified as possible male lovers of Lincoln. Though historical sources show that Lincoln slept with at least 11 boys and men in youth and adulthood, men commonly bunked together in the 19th century without sexual involvement. Lincoln never hid these facts, and his political enemies never tried to use them against him.

Whatever the source of his attraction for Whitman, Lincoln never met the poet, and there is no real evidence that he was particularly aware of him, though there are two possibly apocryphal stories about his "reactions" to Whitman and his poetry. One says that, in 1857, in his Springfield, Ill., law office, Lincoln picked up a copy of "Leaves Of Grass" and began to read it, first silently, then aloud to colleagues. An 1865 letter by a Lincoln aide also reported that Lincoln saw the poet through a window as he walked past the White House, and exclaimed, "Well, he looks like a man."

Mutual or not, Whitman's love for Lincoln would make the president's death a profoundly life-altering event for the poet.

Whitman was close to his mother; his book "The Wound Dresser" is a collection of his frequent letters to her during the war. He was at home in Brooklyn with her when he heard that Lincoln had been assassinated. The news struck both of them dumb. "The day of the murder we heard the news very early in the morning. Mother prepared breakfast — and other meals afterward — as usual; but not a mouthful was eaten all day by either of us. We each drank half a cup of coffee; that was all. Little was said. We got every newspaper morning and evening, and the frequent extras of that period, and pass'd them silently to each other."

Whitman's first poem on Lincoln's death, "Hush'd Be The Camps Today," added to "Drum Taps" only a couple of days later, would vividly evoke how the tragedy got a similar reaction from the recently victorious Northern soldiers. So would his prose account in "Memoranda During The War," titled "Sherman's Army's Jubilation — Its Sudden Stoppage," which recounted how the Northern soldiers' joyfully noisy march through the Carolinas was struck silent when they received the news at Raleigh.

The new man in Whitman's life, Peter Doyle, had been present at Lincoln's assassination. Doyle had gone to the performance of "My American Cousin" in Ford's Theater on April 14, 1865, because he'd heard the Lincolns would be there. He heard the shot and saw John Wilkes Booth leap from Lincoln's box to the stage, but didn't know Lincoln was dead until he heard Mary Todd Lincoln cry out, "The president has been shot!" He was so stunned that he was one of the last to leave the theater, ordered out by a policeman. Pete's vivid account would inform Whitman's famous lecture on Lincoln's death.

Doyle also affected Whitman's popular Lincoln poem "O Captain! My Captain!" Doyle came to America with his mother and three brothers on the William Patten in 1852; the ship nearly wrecked in a storm on Good Friday, also the day of Lincoln's assassination. Whitman knew this. The poem memorializes Lincoln as a ship's captain, who died while guiding his vessel safely to port through a storm. The poem, unlike most of Whitman's, is metered and rhymed. During their walks, Doyle would often quote limericks to Whitman; the poem's extant first draft is in free verse, so he likely revised it to impress Doyle. Another poem written around the same time, "Come Up From The Fields Father," is the only time Whitman ever identified a protagonist with a personal name — Pete. Though they wouldn't always be constant companions, his involvement with Doyle would continue for the rest of Walt's life.

Before Lincoln's death, Whitman's poetry was usually in the first person — but his "I" was not strictly the poet himself, as in today's usual confessional poetry. Whitman's "I" was a sort of cosmic Everyman, speaking at least potentially for the whole human species at its most vibrant and exultant. After Lincoln's death, that persona was humbled, less conspicuous. The lush, sensuous imagery in Whitman's poems was also replaced by symbolism. Whitman's most highly regarded and frequently discussed Lincoln poem, "When Lilacs Last In The Dooryard Bloom'd," exalts Lincoln as the "western star" and casts the poet as a wood thrush, a "shy and hidden bird" whose songs of grief emerge from a "bleeding throat." Similarly, in "O Captain! My Captain!," Lincoln is not the rugged but vulnerable politician Whitman enthuses over in his prose — he is the brave pilot of a storm-tossed ship, facing death rather than abandoning his duty.

Between 1879-90, Whitman would annually deliver a lecture called "The Death Of President Lincoln," heard by many people who didn't know his poetry. The lecture described the murder as vividly as if Whitman had been an eyewitness, and characterized Lincoln's death as a sacrificial martyrdom that resolved all the conflicts of the war. The prestigious venues at which he performed this speech included New York's Madison Square Theater, and the luminaries who attended it over the years included Mark Twain and James Russell Lowell. He gave the talk some 19 times, in Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey and Massachusetts, and it greatly increased his celebrity. Two years before his own death from pleurisy and tuberculosis, Whitman gave his Lincoln lecture for the last time in Philadelphia.

***

The Civil War years were eventful ones for Whitman and his family. Whitman's brother Andrew Jackson Whitman died of tuberculosis in December 1864; in the same month, Whitman had to commit his eldest brother Jesse to the Kings County Lunatic Asylum. In addition to being wounded, his brother George was also held as a Southern prisoner of war for four months that same year. On the plus side, Whitman would meet Doyle, the love of his life, and do substantial work on what would become the most influential and famous writings of his career.

The "Specimen Days" Civil War section ends with a handful of essays summing up Whitman's experiences in the war and his conclusions about its meaning and results. Whitman titled one essay "The Real War Will Never Get In The Books," in the belief that the war's ultimate meaning lay not as much in its historical impact as in its effect on the lives of real people. Despite this prediction, one of his greatest contributions to American history is ours now because he made sure that, in fact, what he considered "The Real War" did get into the books.

Jack Veasey, an award-winning journalist, has written for numerous magazines and newspapers. He has also published 10 collections of poetry, hosted national literary radio programs and was awarded a Fellowship from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.