By Norm Kent

On July 17, 2013, Major League Baseball held its 84th annual All Star Game at Citi Field in Queens, New York, the home park of the New York Mets. It was a day that would become special for the LGBT community.

On that afternoon, Bud Selig, then commissioner of MLB, challenged once and for all homophobia in the clubhouse. The commissioner held a press conference announcing that from that date forward it would be the policy of every major league club "to welcome all individuals regardless of sexual orientation into our ballparks."

"Both on the field and away from it Major League Baseball has a zero-tolerance policy for harassment and discrimination based on sexual orientation," Selig said.

It was nearly two years ago, and Selig declared that a workplace code of conduct "would be created and given to every player from the minor leagues on up. Training sessions and a centralized complaint system will also be instituted."

The commissioner kept his word.

A year later, Selig would appoint a retired gay baseball player, Billy Bean, as a spokesperson for inclusion. Baseball's non-discrimination policies are now posted in every locker room in all their leagues. The Park Avenue home of Major League Baseball has a fully staffed 'Office for Diversity.'

John Rocker

We have come a long way from the afternoon in July of 1999 when John Rocker, the Atlanta Braves reliever, remarked to Sports Illustrated that he hated playing in New York at a Mets game.

"Imagine having to take the train to the ballpark, looking like you're riding through Beirut next to some kid with purple hair next to some queer with AIDS right next to some dude who just got out of jail for the fourth time right next to some 20 year old mom with four kids," he said.

He was excoriated for it even then. The remarks exemplified the homophobia that permeated the game.

Fifteen years later, John Rocker was a surprising representative for a new dawn. Last year, signing autographs in Cooperstown, New York, during Hall of Fame week, Rocker was a different person. He had just finished participating as a contestant in the popular TV show, "Survivor."

"My ally and closest friend was a gay man and his partner," he told SFGN.

Asked how he would feel today about gay athletes coming out in the clubhouse, Rocker remarked, "If a guy can hit my fastball, he should have a right to play. No one has a right to discriminate."

Still, a lot of old timers have not jumped on the diversity bandwagon. When Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, 79 years old, and baseball's first black manager, was questioned about Commissioner Selig's initiative, he refused to comment on it.

In Cooperstown for the Hall of Fame ceremonies, he brusquely stated, "I am here just to sign autographs," and ended the interview.

Glenn Burke

Glenn Burke played for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Oakland A's in the late 70s and early 80s and was openly gay to his teammates, coaches and team owners. It did not go well with his old school manager, Tommy Lasorda. The tension became worse when Burke befriended Lasorda's own gay son, who lived in West Hollywood. Sadly, both would eventually die of complications from AIDS.

Even today, Lasorda cannot talk easily about Tommy, Jr. But it did not stop him from setting up a memorial cancer foundation in his lad's name.

He has evolved, too.

Lasorda, a fierce competitor and Hall of Famer, told SFGN, "I would start anyone in my lineup who could take two, single to right field and help me win a game." In fact, sports announcer Joe Garagiola once joked Lasorda "would throw at his mother if it helped his team."

Many other retired players echo that thought. Tommy Davis, who in the 1960s played on over ten teams in his career all over the country said, "First of all, you play to win. You form a brotherhood based on the talents teammates bring to the field, not to the bedroom."

But sexuality was not an open issue, 'back in the day.'

Terry Collins today is the manager of the New York Mets. He is a personal friend who coached me when I played for 20 years as a member of the Los Angeles Dodgers senior baseball fantasy camps in Vero Beach, Florida.

Collins was also Glenn Burke's roommate in 1976 and 1977 when they both played for the Dodgers.

"Glenn was troubled even then, but the organization did not have any reach out programs in that era," Collins recalled.

In fact, at the time, the Dodgers, the very same team that had broken the color barrier in baseball 30 years earlier, were so homophobic they offered Glenn Burke $75,000 to get married to a woman to cover up his homosexuality.

He declined.

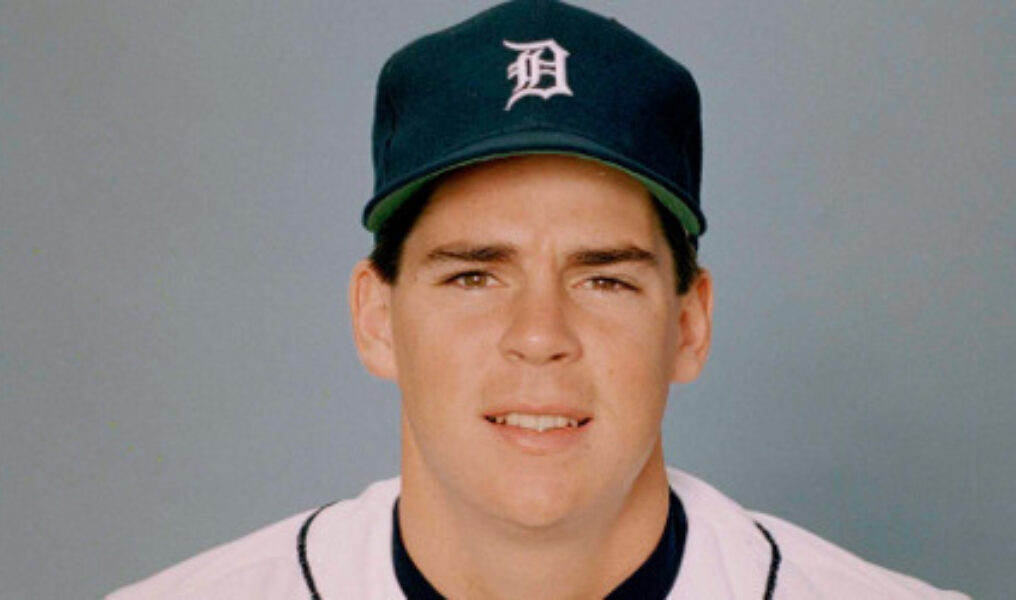

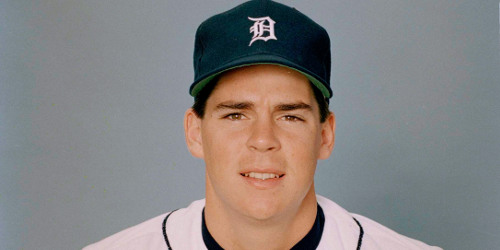

Billy Bean

This year, Terry Collins' Mets were amongst a host of major and minor league teams that held clubhouse and locker room presentations highlighting diversity and LGBT inclusion in the sport. They were moderated by Billy Bean, a one time Los Angeles Dodger himself and former Detroit Tiger.

"I have to look forward to a new generation of athletes who are much more receptive to inclusion than we experienced years ago," said Bean, who came out in 1999 after he retired. "I can't focus on past mistakes. I have to create new opportunities for today's players, create a new vision we can aspire to."

Bean used to live in South Beach and play softball in local gay leagues. He relocated to Southern California to continue his real estate career, after a short run with a Miami Beach restaurant. Today, though, Bean is busier touring minor and major league clubhouses and administrative offices, championing the former commissioner's vision of inclusion.

Bean has been given a new life and new career, one not measured by balls and strikes, but by spirit and energy. He has brought that passion across the country, from the Rookie Career Development Program to diversity symposiums nationally.

"My goal is to create a conversation that is inclusive and accepting, and focus on that," he recently told SFGN. He added, "Hate is not a virtue."

It still isn't easy.

Bean's appearance at the Mets spring training facility in Port St. Lucie still raised eyebrows.

"It's not a lifestyle I agree with," said Mets second baseman, Daniel Murphy, who identified himself as a devout Christian. Nevertheless, Murphy added it was nice to meet with Billy Bean. "You get to meet the man, not the stereotype."

It was exactly what the general manager of the New York Mets wanted to hear. Sandy Alderson had been the general manager of the Oakland Athletics when Glenn Burke was an excommunicated "outcast," living homeless on the streets of San Francisco.

"It's something that was wrong then, and never should have happened," Alderson told the Wall Street Journal in March. "And it can't ever happen again."

Billy Bean added, "I know I won't get everyone to be on the same page. Many of the older coaches come from a different generation set in their ways. And I know my work is not going to be a walk in the park, but it's my responsibility to rise to the challenge and make it better for the next generation of major leaguers."

Bean's own personal journey was made into a video last month, and released on the baseball channel.

"I was humbled," he said. "It brought back tough moments and rough reminders of the way things once were for me. But this new task gives me a chance to promote self-acceptance and change things. My heart and soul are in it."

MLB Office of Diversity

In the meantime, Wendy Lewis, Major League Baseball's senior vice president of Diversity and Strategic Alliances, has her work cut out for her as well.

"We know we are only taking the beginning steps. This is not an office that is going to come and go, but one that will grow and grow," she told SFGN last summer.

Lewis was right on target. She is developing methodologies to enhance diversity efforts, prudently pointing out the potential rewarding economic impact outreach will engage.

"We know there are players who are gay. Of course we do. Everybody is everywhere," Lewis said. "You are fooling yourself if you don't think so. Our obligation to the fans is to create an environment where people are comfortable being who they are. It's our legacy to Commissioner Selig. That was his goal. He did not create this office in response to a crisis, but he did it from the spirit of embracing a community we knew needed support."

'Out' Executives

There was good reason for Selig to act. In September of 2012, Kevin McClatchy, the owner and CEO of the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1996 to 2007, came out of the closet to The New York Times, saying frequent homophobic slurs he heard in baseball circles had convinced him to keep his sexual orientation a secret

McClatchy, an heir to a newspaper chain, followed in the steps of Ric Welts, the president and chief executive officer of the Phoenix Suns, who came out to the media in 2011.

Neither story is isolated.

Veteran Major League Baseball umpire Dale Scott revealed in an interview last December that he is gay and married to his partner of 28 years.

"I am extremely grateful that Major League Baseball has always judged me on my work and nothing else," Scott told Outsports.com, "And that's the way it should be."

Dave Pallone, a former major league umpire in the National League from 1979 to 1988, was not so lucky. Now a diversity trainer and motivational speaker, Pallone spelled out his secret double life in his autobiographical book, "Behind the Mask." His tenure ended in disgrace. Major League Baseball paid him off to leave the sport, after he was falsely accused of being involved in a prostitution ring with younger men.

Openly gay NBA star John Amaechi said once that "homophobia in sport is death by 1,000 cuts." From Glenn Burke to Billy Bean to Dave Pallone, Major League Baseball has had its own share of victims.

Outreach Outside of Baseball

Today, Major League Baseball is not the first sport to become inclusive and reach out to the LGBT community. The National Hockey League and its players' association have initiated the "You Can Play" Project, to promote LGBT outreach and bring an end to bullying.

Its founder, Philadelphia Flyers scout, Patrick Burke, claims the NHL has set the standard for professional sports. His own son, a young gay college student, was killed in an automobile accident in 2010.

NHL commissioner, Gary Bettman, wholeheartedly supported Burke's initiative.

"Hockey is for everyone," he said. "The official policy of the NHL is one of inclusion on the ice, in our locker room and in the stands."

Representatives of all the major league sports were present in Palm Beach Gardens last October for the PGA's third annual "Sports Diversity and Inclusion Symposium."

The PGA of America is the host of a group whose partners include the U.S Olympic Committee, NBA, NFL, NCAA, NASCAR and MLB. The event was designed to recognize, celebrate and encourage diversification in the world of sport.

Cyd Zeigler, the founder and operator of OutSports.com, was one of the presenters. "LGBT organizational policies and practices" was one of the panel discussions. As baseball's Lewis has stated, the era of inclusiveness in professional sports has not only begun, it is here to stay.

Whatever may have been in the past, Major League Baseball is finally at bat and in the game, from sending representatives to the LGBT Sports Coalition last year in Portland, Oregon, to Brian Cashman, the General Manager of the New York Yankees, reaching out this past summer to LGBT at-risk youth in a New York City social services agency.

LGBT Nights at MLB Stadiums

Baseball may have been late to the game, but more than a dozen teams also now have LGBT nights, none more popular than in Wrigley Field where a lesbian, Donna Ricketts, is one of the owners. Even before her family bought the Cubs team, Ricketts was a fund raising executive who led a Super PAC that has a mission to end discrimination against LGBT people.

In conjunction with SFGN's predecessor, the Express Gay News, the Miami Marlins held an "out" night at the ballpark over 10 years ago. The Gay Men's Chorus of South Florida sung the national anthem.

It was the sixth inning and the Marlins loaded the bases with none out. Mike Morse, who helped the Giants win a world series last year, came to the plate.

A loud and plastered Braves fan stood up and yelled, "This isn't San Francisco; you fag. We got babes here on South Beach."

If he only knew.

Sean Flynn, the Senior Vice President for Marketing for the Miami Marlins, is the individual who as far back as a decade ago promoted media partnerships with the Express Gay News.

In the inaugural issue of SFGN in 2010, the Marlins also took out the entire back page.

"We have always recognized that South Florida is a diverse and accepting community, and we have tried to reach out to everyone. It's the way it should be."

Flynn had an inclusive marketing plan, but he was not helped when the Marlins brought Ozzie Guillen in as their field manager. He immediately created a stir for saying to the South Florida Cuban community which is the Marlins fan base that Fidel Castro was a nice guy he admired, and would not mind having a beer with.

Known for his off the charts comments previously, Guillen, while the White Sox manager, had once told the Chicago press, "You can't make homophobic slurs and do gay bashing in the mass media… you have to leave it in-house."

Guillen epitomized the homophobia permeating baseball's soul. He reasoned that if you leave it in the locker room, "no one will say anything about it publicly because then everyone will know they're a fag."

Now retired, it is unlikely that the immediate past commissioner of baseball, Bud Selig, would agree. In fact, remarks as ignorant as Guillen's may have inspired Selig's vision for a newer tomorrow.

"Baseball is a social institution with an important social responsibility to be open minded," he said. "It has to be part of our DNA. We have to be on the right side of history."

In their offices, baseball is doing its part.

When a baseball player finally comes out of the closet while still in uniform, the sport will have a chance to test out how their game plan is working. In the meantime, Major League Baseball is making a pitch to allow that athlete to step up to the plate without fear of retribution.

Like Tommy Lasorda said, if he can take two inside and then line a base hit to right field, that will be all that matters.