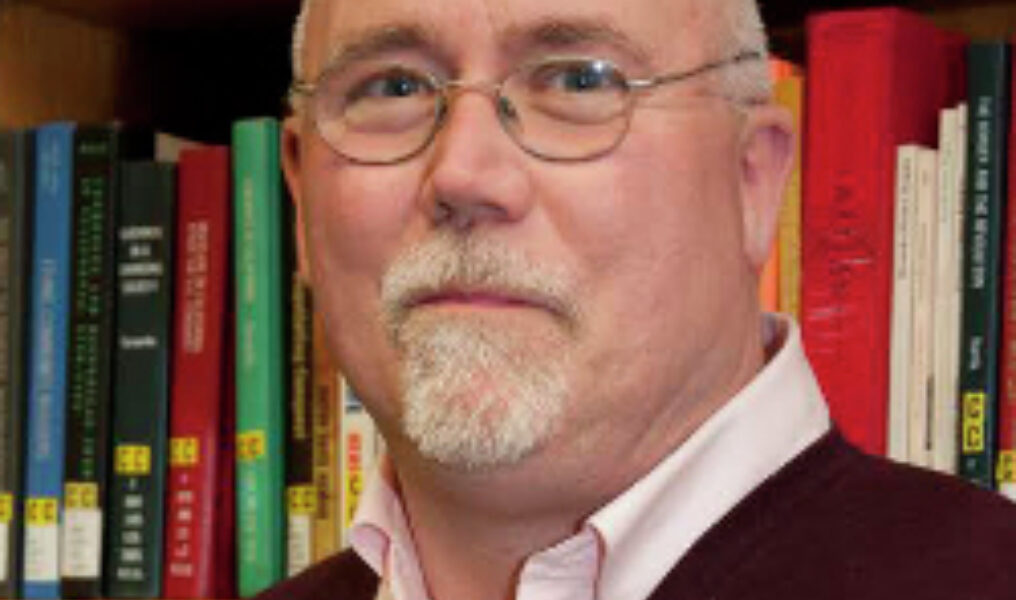

BY TIM RETZLOFF

I knew criminal court cases could be a gold mine for researching LGBTQ history. I did not know such records were so vulnerable.

As I recounted in an earlier blog post, my path to queer remembering started in the late 1980s with looking into old gross indecency and sodomy cases at the Genesee County Court House, unkind clerical staff and all.

When I moved from Flint to Ann Arbor in 1995, I had good reason to delve back into court records. From a pioneering expose written in 1977 by Daniel Tsang for the Midwest Gay Academic Journal, I knew that the University of Michigan had engaged in highly publicized crackdowns on homosexual activity on campus in the late 1950s and early 1960s. From my Flint research, I knew that court documents promised to yield more details.

I made an initial survey of Washtenaw County criminal records in the summer of 1998, making notes and copies from a sampling of the cases. Of more than 200 cases, I managed to look at thirty-five.

From these, I found that those arrested were typically prosecuted as felons for attempted gross indecency; they typically pled guilty; and Judge James Breakey typically sentenced them to five years of probation, a $275 fine, and ten days in the county jail, in some cases to be served on weekends "beginning at close of present semester."

As I later learned from my work on Detroit, such treatment was particularly harsh. Detroiters who tried to pick up undercover police officers in the same years as the Ann Arbor crackdowns usually faced charges of accosting and soliciting for immoral purposes, a misdemeanor, and after pleading guilty were given thirty days in the county jail, which was waived if the defendant paid a $50 fine, plus one year of probation.

The Ann Arbor police who conducted the decoy operation learned such techniques as foot tapping for attracting homosexual come-ons, unlawful as they were, thanks to training from the Detroit Vice Squad. Patrolman Herbert McGuire revealed this connection in testimony given in one of the U of M cases after the judge cleared the courtroom. See Examination before Judge Robert L. Shankland, December 14, 1959, Criminal Case no. 11-893 (1959), Washtenaw County Clerk Files, copy in possession of author.

The original of this 30-page document no longer exists. Within just a few years after county staff photocopied it for me, county staff destroyed it.

On June 30, 2001, I returned to review the Washtenaw County records more thoroughly in preparation for a conference paper. I learned then that the files had been purged of all documents except for the sentencing and final disposition.

"So much for permanent retention," I wrote in my journal that day. "Trying not to feel so devastated."

The systematic destruction of documents applied to all criminal records that had not been active for twenty-five years, a span then covering 1880 to 1975. Nearly a hundred years of records were shredded per proper bureaucratic procedures.

I obsessed over the evidence that had been lost. I could barely sleep for nearly a week.

Besides handicapping my own study of gay and bisexual men in Ann Arbor, this act of bureaucratic shortsightedness, implemented under the authority of Washtenaw County Clerk Peggy M. Haines (whose name remains etched in my mind), constituted an incalculable gutting of a crucial body of rich source material for local social history. Untapped evidence that might have shed new light on Prohibition, or on the Students for a Democratic Society, or on marijuana prosecutions prior to Ann Arbor's famous five-dollar fine for a joint ordinance, was gone forever.

Is gone forever.

When I decided to focus on lesbian and gay life and politics in Metro Detroit for my dissertation, I knew that the criminal files from the Detroit Recorder's Court would yield riches, as would court records for Oakland and Macomb County. To my great relief, I confirmed that they had all been microfilmed.

Mining them required more than eight months of looking through over 100,000 unindexed cases from 1944 to 1965 in order to locate about 1,200 that were relevant to my project. These cases did, indeed, prove invaluable to understanding city, suburb, and the changing map of queer Detroit in new and nuanced ways.

To this day, I think about the detailed Ann Arbor project that might have been. I feel haunted by how much of Ann Arbor's past, queer and otherwise, was so thoughtlessly and needlessly purged.