At this point in his life, Charles Alexander is a venerable institution in Detroit's LGBTQ community. A look at the 83-year-old artist and activist's achievements and the significance of his contributions to the community are clear: He has earned a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Pride Awards, the Jan Stevenson Award for service to the Affirmations LGBTQ community center, several Spirit of Detroit Awards and various other recognitions thrown in for good measure. Beyond those achievements, he's made his mark on Between The Lines, having written for the paper since day one and in total penned some 700 Parting Glances opinion pieces. A prolific artist as well as a renowned one — at times producing at least one fully formed artwork a day – Alexander has also given charitably, donating regularly to HIV/AIDS and LGBT causes.

So, as the news began to spread that Alexander had suffered a stroke and heart attack on Memorial Day of this year, many were shocked and saddened. Left weakened and somewhat visually impaired, Alexander spent three weeks recovering in the Detroit Receiving Hospital before doing another six in rehab at Henry Ford Village in Dearborn. Following rehab, Alexander, a fixture in the small Wayne State campus area in which he had lived for more then 30 years, moved into a small independent living unit in Henry Ford Village.

Now, as Alexander struggles to recover, a new show featuring pieces of his art prepares to open at the Pittman-Puckett Gallery inside Affirmations. Proceeds from "A Life Well Lived: A Celebration of the Art and Work of Charles Alexander" will benefit The Charles Alexander Care Trust. In advance of the show, Alexander sat down with Between The Lines to talk about his art, his recovery and his life.

What's the last thing you remember prior to having your heart attack and stroke?

I was simply sitting on my porch and I decided I wanted to get something to eat. I wanted to get a banana and a cookie, and a block away is a gas station. So I went there and I got those things, but I also got something called Vanilla Coffee Mix. And I drank that and had this scary reaction to it, so scary that I got Dustin Blitchok, who lived above me, to take me to the hospital. That's when they said that I had had a stroke and a heart attack.

And after?

I don't remember anything from Receiving Hospital. After that, I went through rehab here at Henry Ford Village and I will say this: the care that I received here was excellent. The therapy that I was given here was very good. There are two kinds of therapy. There is physical therapy, which is using weights, and occupational therapy, which is doing things like standing and folding linen — things that you would be doing at home. And what was interesting was to see those adults who were in their 70s and 80s, maybe late 60s, doing their assigned exercises and it was a rather moving experience to watch how these older people tried to do everything they were assigned to do. They really worked at it. And it eventually brought me to the final realization that the last coming out process is coming out to old age. Many of us think of ourselves as mentally 35 or 40, much younger, and I'm coming to the realization that old age happens. And that some of it's a real, real challenge because of what you have to go through following a stroke or difficulties with health and so on.

How has your life changed since your stroke and heart attack?

Prior to my stroke, about a year, I was bicycling on weekends, usually — sometimes 10 miles or 20 miles. I also bicycled in the Tour Detroit, which is 30 miles, and I did that twice. And as a teenager, into my 20s, I was a roller skating enthusiast. So, I have a lot of things I've done using my feet and so forth. So, not being able to do that is kind of frustrating. I have some difficulty walking, even with a walker. I went through the rehab center and I was making good progress, being able to do some walking with a walker and without a walker. But for some reason, recently, I slipped and kind of banged my side and so it's been difficult for me.

For those who don't know, you didn't drive. You were always walking and were well-known in your Wayne State neighborhood, a regular at Cass Café and Shangri-La and other spots. What has it been like to lose so much of your mobility?

It's a change not to be able to come and go as you once did. Not to have the freedom that you once had. You've become essentially a different person. You've left somebody behind that you could come and go with ease. It's difficult. It's difficult.

Let's talk about your art. It all started at Cass Tech, right?

I got good training at Cass Technical High School, where I was a commercial arts major. One of the interesting things about Cass Tech is that art students and music students, we all shared the same floor. That's where I first made my early gay contacts, because there were other gay students there and we began to bond with each other.

Following high school you would go to work various jobs – as a stringer for the Free Press, a PR man for the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and even as an operating room technician at Harper Hospital – before finishing college and going on to work for 28 years with the Detroit Public Schools. But you lost touch with your art and it wasn't until you got sober that you reconnected with it. Is this right?

It was 1981. I reconnected with my art at Cottage Hospital, where I went for rehab. Sometimes in the rehab programs, you're given assignments to make you think, to keep you occupied, to make you feel good about yourself. The assignment we were given was to go through magazines and cut out pictures indicative of our mood. In my haze, I misunderstood and instead of cutting out pictures I turned them into collages.

And I did several collages, cutting and pasting. One of the nurses even offered me money for one. Then, when I got out of rehab, I took and concentrated on my sobriety, cut down on my coffee consumption, started taking good vitamins and other things to help my rehab. And then, I had the collages that I did mounted and framed. I had a friend who was teaching art at one of the community colleges. He said, "These are good, take them down to the Detroit Artists Market for jurying." And so, I took three pieces down and all three pieces got into the exhibit.

Then the next thing that came along was, of course, the AIDS crisis, so I began making art and donating art for AIDS fundraising. Overall, I raised with my art several thousand dollars for AIDS. And I've been going ever since then.

Your upcoming show features many pieces of your art —

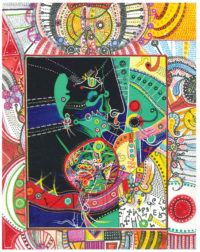

Yes, and six of those pieces of art were done after the stroke. Jon Strand, a friend and well-known artist, gave me art supplies and encouraged me, saying, "It would be good therapy for you to do some art." It was difficult because I've had problems with my vision due to the stroke. But, nonetheless, I was able to create six or seven pieces of art, and they are in the exhibit and they're called "Stroke Rehab 1," "Stroke Rehab 2," etc., etc.

You haven't done anything since those initial pieces, though. Is there are a reason you haven't done more?

Well, those pieces were challenging. And somewhat amazing for me is that in spite of the vision difficulties, that they actually came out with a freshness, an automatic-ness. If you read my column, "How I create My Art," it will give you an idea of how I do my art. It just really flows through me.

What was it like to see such a large collection of your work altogether?

What was it like to see such a large collection of your work altogether?

There is a very special experience. The experience being: you've done a piece of art and you've forgotten about it and time passes by and somehow, by chance, you get to see that piece of art, and it's as though you're seeing it for the first time. And you think, "Wow, did I do that?" It's the same thing with writing.

What purpose has your art served over the years? What has it given you?

Well, I've been sober 38 years and what has happened is I've substituted one addiction for another, the addiction being my art. I don't think about it. I just do it. It unfolds. It happens. And what I try to do with my art is make it such that the person who views it gives their own interpretation to it. Brings their own feelings, brings their own insights, brings themselves into the picture. And I think if I've succeeded in doing that then it's successful. In other words: it's sharing your gift with someone else. I believe if you're given a gift, if you're born with a gift, [if] that gift is watched over and cared for over the years and shared, brought into fruition, then you've done your good.

"A Life Well Lived: A Celebration of the Art and Work of Charles Alexander" is now up in the Pittman-Puckett Gallery inside Affirmations. The exhibit was arranged in the Affirmations gallery by Scarab Club Gallery Director Treena Flannery Ericson. An official opening for the show, which Alexander is planning to attend, will take place Sunday, Sep. 29, from 4 to 7 p.m.