By Bridgette M. Redman

There is a place insomniacs visit that is more vivid than reality and more grotesque than any nightmare. It is a barren, lonely vista where time no longer exists and the past tumbles together with the present in an attempt to determine the future.

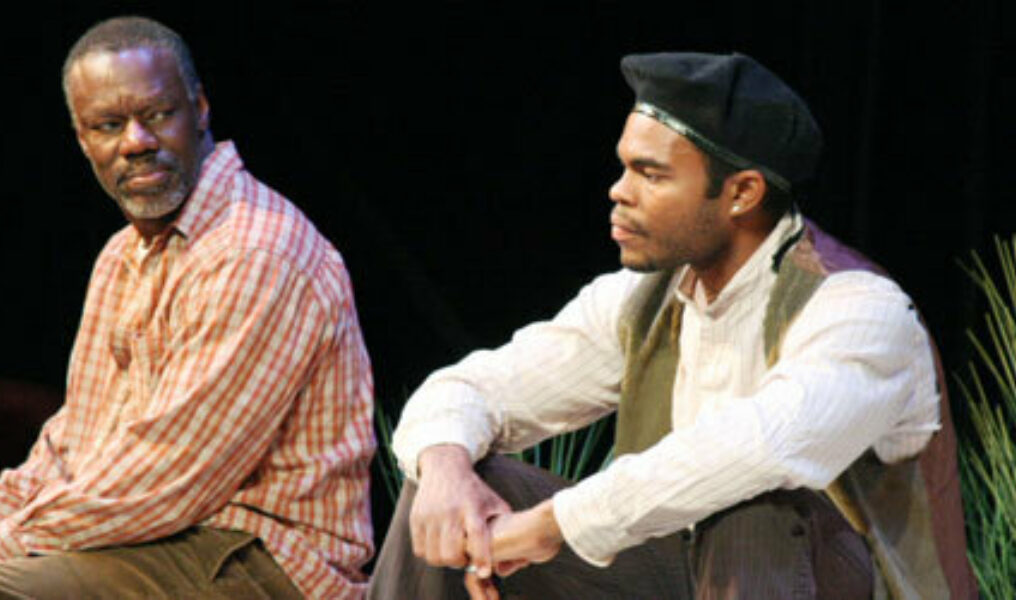

At Williamston Theatre, the cast and crew of "Blue Door" capture the late-night clarity of an insomniac's struggle in their incisive and haunting production of Tanya Barfield's play. Lewis, a mathematics professor whose wife has just left him, is seeking solace in a bottle while trying to make sense of his loneliness and loss. His careful, analytic approach gets interrupted by his dead brother, Rex, who storms into his head and demands that he look to his heritage for the answers to his woes.

Like all Williamston shows, "Blue Door" sends its audiences home with much to ponder and discuss. While Lewis' heritage and the oppression that shaped it are uniquely a part of the African-American experience, the themes are ones that people of any race can relate to. For "Blue Door" asks us to contemplate whether fleeing from our heritage is a form of self-loathing, and challenges us to find a way to understand the effect that the past has on our present and come to peace with it.

Rico Bruce Wade infuses Lewis with dignified self-denial, an escape artist who deals with issues of race, self-identity and personal crisis by compartmentalizing and ignoring. He hasn't made peace with his past; he's avoided it and pretends he is unaffected by it. His skilled acting keeps Lewis' inner monologue from becoming self-indulgent and bars any dishonesty from his denial. Instead, he slowly reveals himself, believably taking the audience on a journey through four generations.

Lewis is a man who believes he has risen above his past and that its horrors can no longer touch him. He shuts out his family from his memories, not noticing that he is isolating himself from those still inhabiting his life.

When Julian Gant's Rex confronts him and accuses him of ignoring his race and washing his hands of his identity, Lewis fights back aggressively claiming he wants no part of the "black mafia" that accuses African-Americans of not being black enough.

Gant has the far more challenging role of the two, as he portrays all of the spirits who come to haunt Lewis during his sleepless night. It's a rich role in which he creates three of the four generations of men — and all the miscellaneous characters who show up throughout the play, including scenes where he talks to himself, such as when he switches between Lewis' great-grandfather, Simon, and a Klan ghost at his door. Gant is relentless in his portrayal of the past, whether with the bitter rage of Rex or the easy-going optimism of Simon or the stubborn idealism of Jesse, Lewis' grandfather.

Wade also portrays both sides of conversations, but except for the times he slips into the role of his father, Charles, it is always Lewis reporting the other person, not Wade becoming the other character — for this is Lewis' brain that the play inhabits and he cannot escape himself. Gant, on the other hand, is the antagonist that Lewis would shut out, the one who shows Lewis just how divorced he has become from all that matters in his life.

While the play dwells upon some harsh, painful events, director Suzi Regan keeps air in the piece by finding appropriate moments of bleak humor in the script. She also brilliantly contrasts Lewis' relative stillness and careful, controlled movements with the high energy and movement patterns of Gant's characters. Lewis rarely leaves the over-sized book that dominates center stage, while Gant's characters stride from one side of the theater to the other, only rarely taking up one spot to inhabit.

Teamwork was also evident in how each of the members of the technical crew contributed to the overarching vision of the play. Bartley Bauer's set established the dreamscape of Lewis' mind. Parched and cluttered with books and sprigs of green, it held the remnants of those few things Lewis wanted to keep. It also held the door — the door that his ancestors would paint blue to keep the evil spirits out and the soul of their family in.

Donald Robert Fox's lighting had very few cues, but those it did included complex specials ranging from starlight to a panorama of mathematical equations that splattered the backdrop when Lewis remembered his lectures.

Early in the play, Lewis tells his brother that he has risen above his family, that he is different, that he is better. As the sleepless night wears on, he revisits the stories of his ancestors and begins to understand how they meld with his and how their story IS his story. It's a journey beautifully depicted by the team at Williamston Theatre. While many of the images in the story are violent and painful, the play ends on an uplifting note that chimes hope for the human spirit.

REVIEW:

'Blue Door'

Williamston Theatre, 122 S. Putnam Rd., Williamston. Thursday-Sunday through Oct. 17. $15-$24. 517-655-7469. http://www.williamstontheatre.org.