The death of a child is the stuff of nightmares for parents. The pain and the anguish never really go away, and the entire family is reshaped by such a tragic event.

Such was the case for Rogério Pinto, professor and associate dean for research and innovation at the University of Michigan's School of Social Work, after the death of his three-year-old sister Mar√≠lia in a devastating accident when Pinto was ten months old.

"When people die or get maimed," Pinto tells Pride Source via phone, "it traumatizes the entire family. And because it is preventable, [it causes the family] an enormous amount of guilt. I have heard so many different narratives of what happened to my sister in an attempt to make sense of it, in an attempt to help people survive the pain that they feel and the guilt for not being there, for not watching her."

Marília was hit and killed by a bus in front of the housing project where her family was living in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. On that bus was Marília's mother.

As Pinto tells it, Marília died in front of their mother, who picked the girl off the pavement and brought her inside, laying her out on the family's table.

"Even though I barely knew her, I vicariously absorbed a lot of those narratives of guilt and of loss and of fear that this can happen again," Pinto recalls. "My mother used to go to the cemetery every day. And guess who she took with her?" Pinto accompanied his mother on a near-daily basis.

"My mother found solace in telling how my sister died to anyone who wanted to listen," he says. "When my mother passed away in 2012, I felt compelled to tell the story for me and for my mother."

Pinto uses art to tell the story of his sister, his mother, himself and the rest of his family in his installation titled "Realm of the Dead," on display at the U-M School of Social Work through Oct. 17.

"Realm of the Dead," which took two years to complete, consists of a series of vintage suitcases and trunks that Pinto has turned into sculptures, each one telling the story of a different part of Pinto's life, including growing up in poverty, the death of his sister, his relationship with his mother, molestation by his father, immigrating to the U.S. at age 21 and living undocumented in New York.

Each piece of luggage took Pinto weeks or months to complete. "Some need to be reinforced before we can create anything on or inside them," he says. "We asked a lot from each of them as we hammered, glued, and stapled many objects to them, changed the linings, and rearranged their original designs. Depending on the emotional content going into a box, the transformation can take, as I say, more than a month, maybe several months."

The "Mother" case, which Pinto used to convey his feelings toward his mother, took him "about a year to find and to finish."

"Mother," Pinto says, "is a large metal trunk which was painted white with a touch of green. We reinforced the entire trunk with plywood and lined it with velvety dark green fabric representing the trees and grass my mother loved." At the bottom of the trunk, Pinto says, he placed clothes and jewelry that represented what she wore for her funeral and the urn that would hold her ashes.

He also included an image of Brazil's patroness Our Lady of Aparecida, which is also his mother's name. Aparecida means "apparition" or "appeared" in Portuguese. The installation also includes a painting of a bull that his mother made for him. "I think of it as her self-portrait. So her trunk includes that painting plus a picture of her separated by a net indicating the space between life and the afterlife, the place she is reunited with my deceased sister, the inspiration for the entire exhibit, 'Realm of the Dead.'"

Gender identity plays a big part in Pinto's work. Pinto, 56, identifies as gender non-conforming and uses he/him/his pronouns.

The project draws from Pinto's "Marília," a solo theatrical performance he wrote and performed in 2015. "There's a scene in this installation performance and the original play where I say that at the end of the day, I don't know where I start and where I end when I have all my sisters and my mother inside of my head," Pinto says. "I have been influenced by them so much."

Having these "very powerful women inside" makes Pinto "feel much more like one of them." Pinto has two older brothers. "One of them is gay, as well," he says. "[But] I feel much closer to my sisters in terms of gender identity than I do to my brothers."

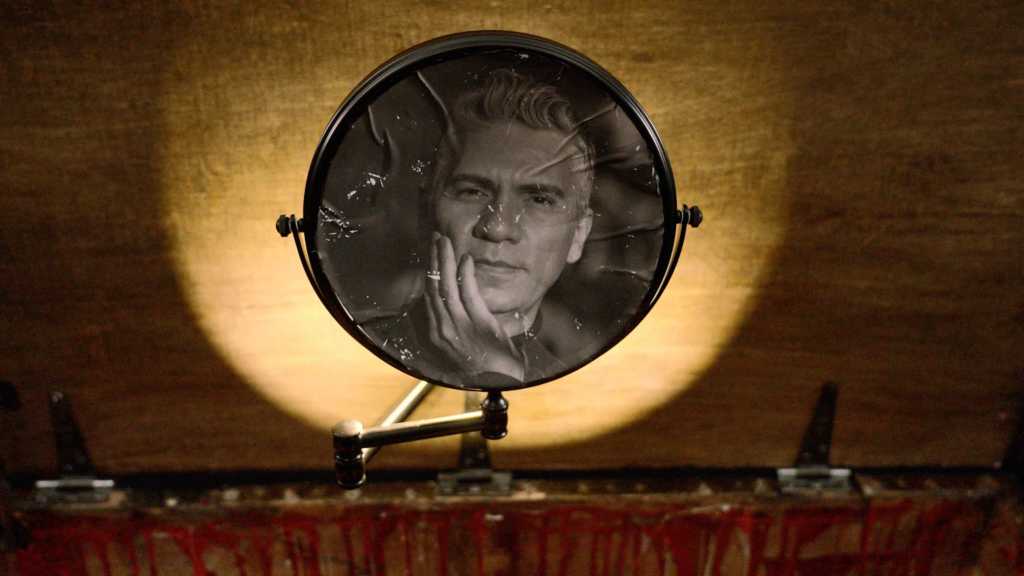

Professor Pinto getting ready for a performance. Photo by Nikki Williams

Still, Pinto doesn't see gender as a binary. "I think that I'm a mix of the usual stereotypical things that we say are female or male," he says. "Working out my gender identity was coming to this moment of comfort. [To] me, it's not any more one or the other. It's what I have recreated for myself. It gives me so much more peace."

Pinto's gender identification is very much influenced by his sister's death. "I will never really completely let go of her or the idea of her, and in some ways, I think that I am her," he says. "Not in any pathological way, but I think that I absorbed a lot of her."

"In many ways, my family treated me like a replacement," he says. "Not a replacement that was made to replace her because I was already there. They were missing her. They were mourning her, so it was very easy for them to approach me as the continuation of the little girl they lost."

Now, at age 56, Pinto is still questioning how gender identity is formed and how the events of his childhood have shaped his life. He hopes that his work will inspire others to look inward.

"I hope it will inspire people to use creative means to heal themselves," he says. "It could be a poem; it could be arts and crafts, anything that allows someone to get out of one's mind and create something."

Art, Pinto says, has the ability to help people understand and work through difficult feelings and ideas.

"Research shows that the pursuit of art-based projects and the experience of visual and performing arts can be really good for one's well-being," Pinto says. "As you begin to be able to heal yourself — when you begin to feel better — some space begins to open within yourself so that now you can accommodate someone else, or you can begin to accommodate the plight of another person."

Going beyond individual healing to advocate for broader structural change, he says, is the ultimate goal.

"Anyone who has a mission to help other people really needs to heal themselves first," Pinto says. "I will have more energy and more emotional space to help the next person." He likens this concept to the airplane safety instructions to place your own mask on before helping others. "Things become easier to entertain when you heal yourself from whatever wounds you may have."

While the subjects in Pinto's work are deeply personal and many are difficult for us as a society to discuss, he describes the work as "self-healing."

"I hope that by showing my vulnerability, more people will do the same," he says. "Community mourning and healing is what I think gave me the strength to write the text and conceive the pieces of the exhibit."