Sex, Detroit and The Historic Woodward Bar: How This Journalist’s Debut Novel Incorporates All Three

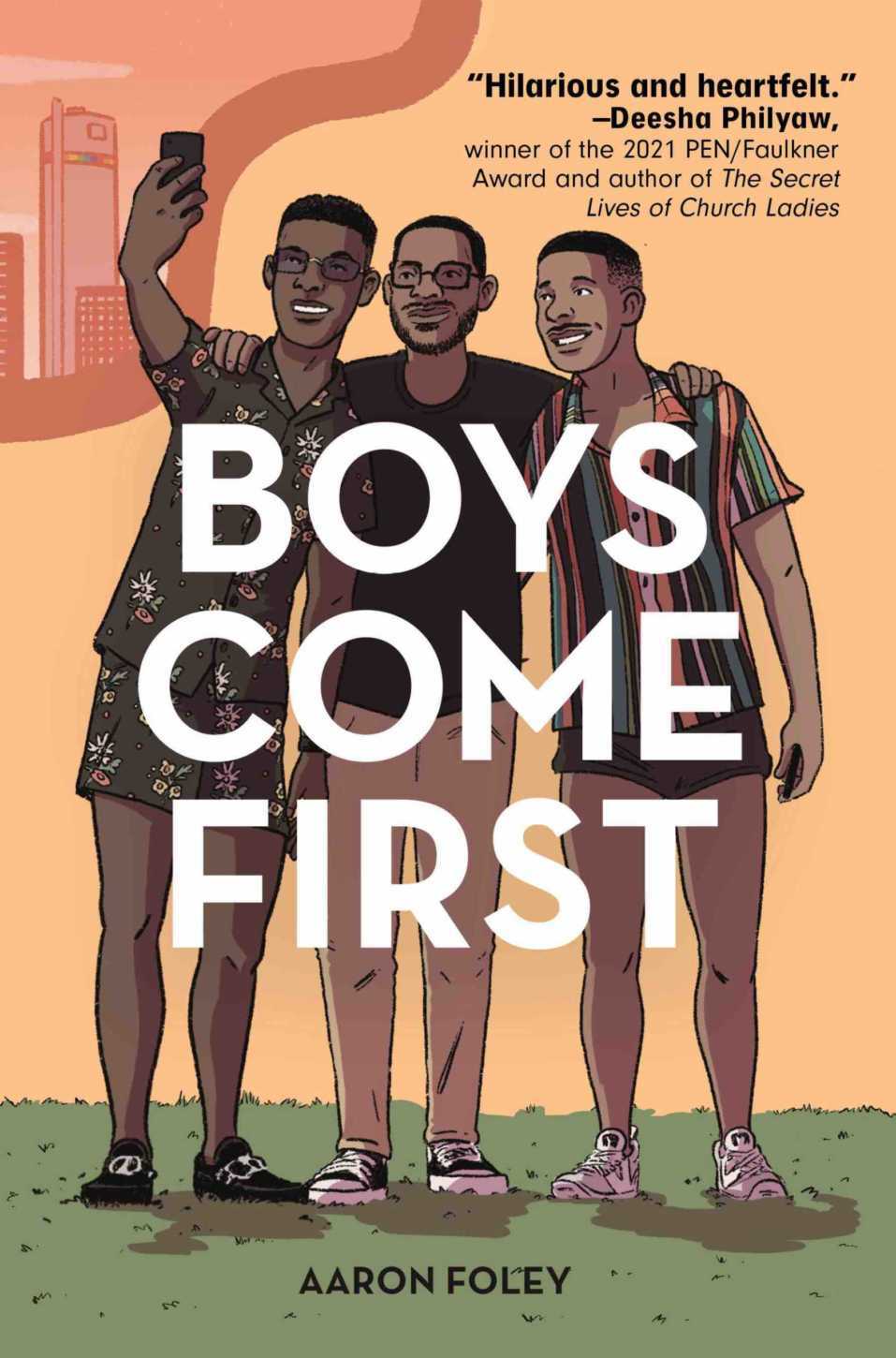

Aaron Foley’s ‘Boys Come First’ follows three Black gay men in Detroit

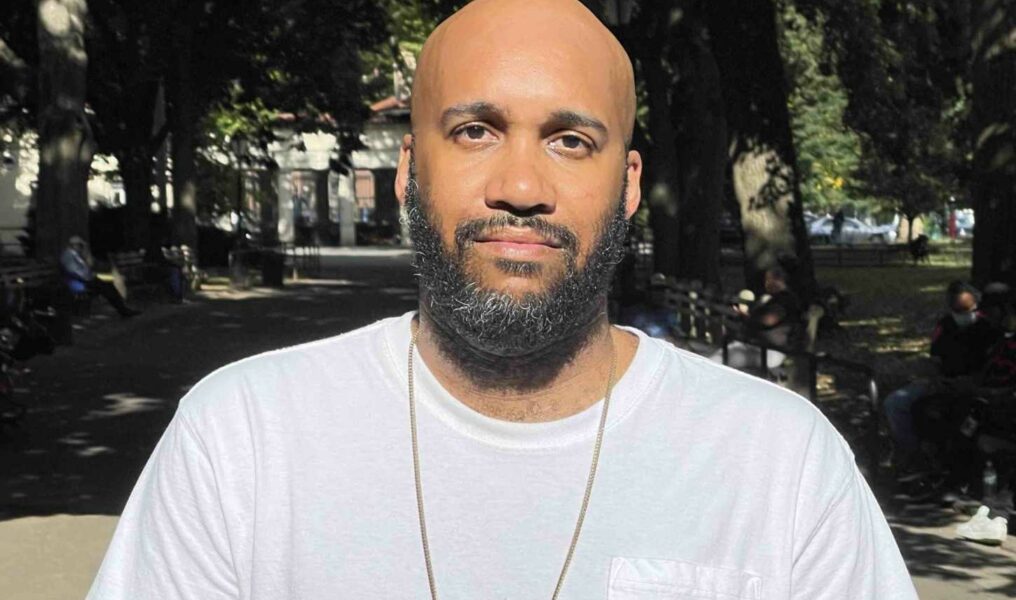

When Aaron Foley heard about the recent fire that burned down the historic Woodward Bar & Grill, notably the oldest LGBTQ+ bar in Detroit, he couldn’t stop clicking refresh. The native Detroiter, journalist and author somberly watched updates from hundreds of miles away in New York City.

“I was looking at these really horrific pictures. Drone shots of this fire at the Woodward. I was in disbelief,” he says from his place in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. “The gay scene literally changed overnight.”

The Woodward Bar & Grill plays a prominent role in Foley’s debut novel “Boys Come First,” which follows the friendship of three Black gay men in Detroit. One of those guys is Dominick, who has one goal: he wants to be married before he turns 35. After losing his advertising job and his boyfriend, all within 30 minutes, he moves from New York City back to Detroit as the clock continues to tick. He reconnects with his best friend Troy and meets Remy, a real estate agent who specializes in the Villages of Detroit. The storyline luxuriates in the Motor City, as it explores the bonds of friendship, gentrification and the idea of Old Detroit vs. New Detroit.

In addition to establishing the Woodward as a home base for the men in “Boys Come First,” the book also bar hops, with memorable shout-outs to Menjo’s, Adam’s Apple, Gigi’s and the Hayloft Saloon.

The author was in his early 20s when he started going to the Woodward, which he recalls playing “gay music, house music, hip-hop, rap, R&B.”

“There was nothing quite like it,” he says. “It felt like a straight club that attracts a mostly gay audience.”

“In San Francisco, the gay bars are pulsating, electronic, EDM-type vibe, and people get down to it. But there’s nowhere quite like the Woodward because there, people are also doing the Detroit hustle. You just don’t see that elsewhere.”

Foley’s early exposure to gay clubs happened after he came out while a student at Michigan State University. At the time, there were two gay bars in Lansing’s Old Town: Spiral and Esquire. Both, he says, “offered standard-issue gay club dance music, neon lights. Mid-Michigan appeal.”

Eventually he set his eyes on the city.

“In Detroit, there’s a porous color line between Ferndale/Royal Oak gay bars and the ones in Detroit,” Foley says. “I wager to say a lot of queer Black folk stay within the city limits.”

Foley found himself drawn to events geared toward Black queer people, like Hotter Than July, founded in 1996 to celebrate Detroit’s LGBTQ+ community. “I feel like I’m at home with my people,” he says about attending HTJ in the past, where he has seen “people vogueing, things that are firmly rooted in Black queer culture. And of course, the music’s good. We need something like that in Detroit.” (This year’s event will be held Friday through Sunday, July 15-17.)

Community gatherings provide an opportunity for connection and cultural storytelling, the things that propel Foley’s writing, no matter the form. He spent 10 years telling community stories as a reporter for the Lansing State Journal, then continued this path as editor of BLAC Detroit magazine. In 2020, he was appointed founding director of the Black Media Initiative at the Center for Community Media at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.

From 2017-2019 he worked as the City of Detroit’s storyteller, a new aptly named position created by Mayor Mike Duggan to give voice to the people who live there.

The TEDx-Detroit Talk vet (he presented at the Fox Theatre, and again virtually during the pandemic) gave one presentation on “How to Live in Detroit Without Being a Jackass,” which is also the title of one of his books. In it, he offers essential advice, notably how to avoid acting like an ignorant racist when you talk to a Black person.

Foley currently works as senior editor at PBS NewsHour in New York City. He considers that his day gig, saving evenings and weekends for his creative work. It’s in this time that he wrote “Boys Come First.”

While the novel allowed him to let loose creatively, writing the authentically hot sex scenes gave him pause.

“I was like, my parents are gonna read this at some point,” he says, laughing. “But I can’t censor myself for my parents. This is real life. It’s what people do. It’s what my friends do.”

And when his friends do talk about sex, Foley takes good mental notes. Getting graphic helps other queer men feel like they are part of the conversation, he says. The dirty details pay off in “Boys Come First” during discussions about modern-day lube options (still using Anal-Ese? Girl, please.), bottoming for beginners and snorting cocaine off an erect penis.

And yes, Foley’s mom has read the novel. She loved it so much she couldn’t put it down. But no, she didn’t mention the sex scenes, though she did tell him she wasn’t a fan of the drug use. (He told her not to worry!) His father hasn’t read it yet, “but I always tell him ‘no rush.’”

Foley’s parents raised him in a “very traditional household” in the Russell Woods neighborhood on the west side of Detroit, during what he calls the Old Detroit era. Kids on his street listened to slow jams on WJLB radio, years before it was owned by iHeartMedia Inc. Everyone in his class had school teachers who looked like them — teachers who were Black. Same with city politicians and leadership.

“So I think when we talk about having role models, having people to look up to, and always being aware of your identity but never having to feel uncomfortable in it, that’s what I mean when I’m talking about Old Detroit,” he says.

But today, he says the vast majority of New Detroit folks don’t have that connection; elements of Old Detroit from his childhood and young adulthood have simply vanished.

“When we walked down the street, every house was occupied. We knew each other on the block, but obviously the forces of economy disrupted so much of that,” Foley says. “There are definitely people of a certain age group who remember what Detroit was and are still grappling with what it’s like to be in Detroit now.”

As gentrification took hold and rapidly changed the face of downtown, Foley and his friends witnessed the transition from Old Detroit to New Detroit. This shift brought with it more questions, ones that ultimately found their way into his book.

“Boys Come First” was written in Detroit shorthand — by a Detroiter, for Detroiters. So he casually drops “The Giant Slide,” “the big tire” and Charles Pugh. For out-of-staters: The slide is on Belle Isle; the 80-foot-tall landmark UniRoyal Tire is along I-94, south of Detroit; and, well, you can look up Charles Pugh on Google. He gets the prize for this line, perhaps his most memorable use of Michigan nostalgia: “I can ride dick like the penny horse at Meijer.”

“We started looking at Detroit for what it’s becoming as opposed to what it was. How that impacts what some people are experiencing,” he says. “Do my actions contribute to the eradication of Old Detroit? Do they contribute to a certain kind of gentrification? Where do I stand? Do I preserve the old or go toward the new?”