Jeffrey Montgomery (May 9, 1953 – July 19, 2016) Photo: Ron Miotke

The man who took personal tragedy and turned it into a "brilliant" career fighting for the rights of the LGBT community has died.

Jeffrey Montgomery, the founder of Triangle Foundation in Detroit, died Monday, July 18 at age 63.

Montgomery's life journey took him from a comfortable childhood in Grosse Pointe, Michigan; to the national stage as a leading voice combating anti-LGBT violence across the U.S.

"No other local activist for LGBTQ rights and sexual freedom from the past twenty-five years has had the potent impact on our history as Jeffrey Montgomery," said Tim Retzloff, adjunct assistant professor at Michigan State University who has extensively studied the LGBTQ rights movement in Michigan. "His unflagging devotion to queer justice and social justice will be a model for generations to come."

Montgomery graduated from Grosse Pointe High School, where he served as the president of the student body, and went to Michigan State University. He said in his senior year in high school he flirted with the secret gay community in Detroit, visiting an adult bookstore. Soon he was visiting local gay bars.

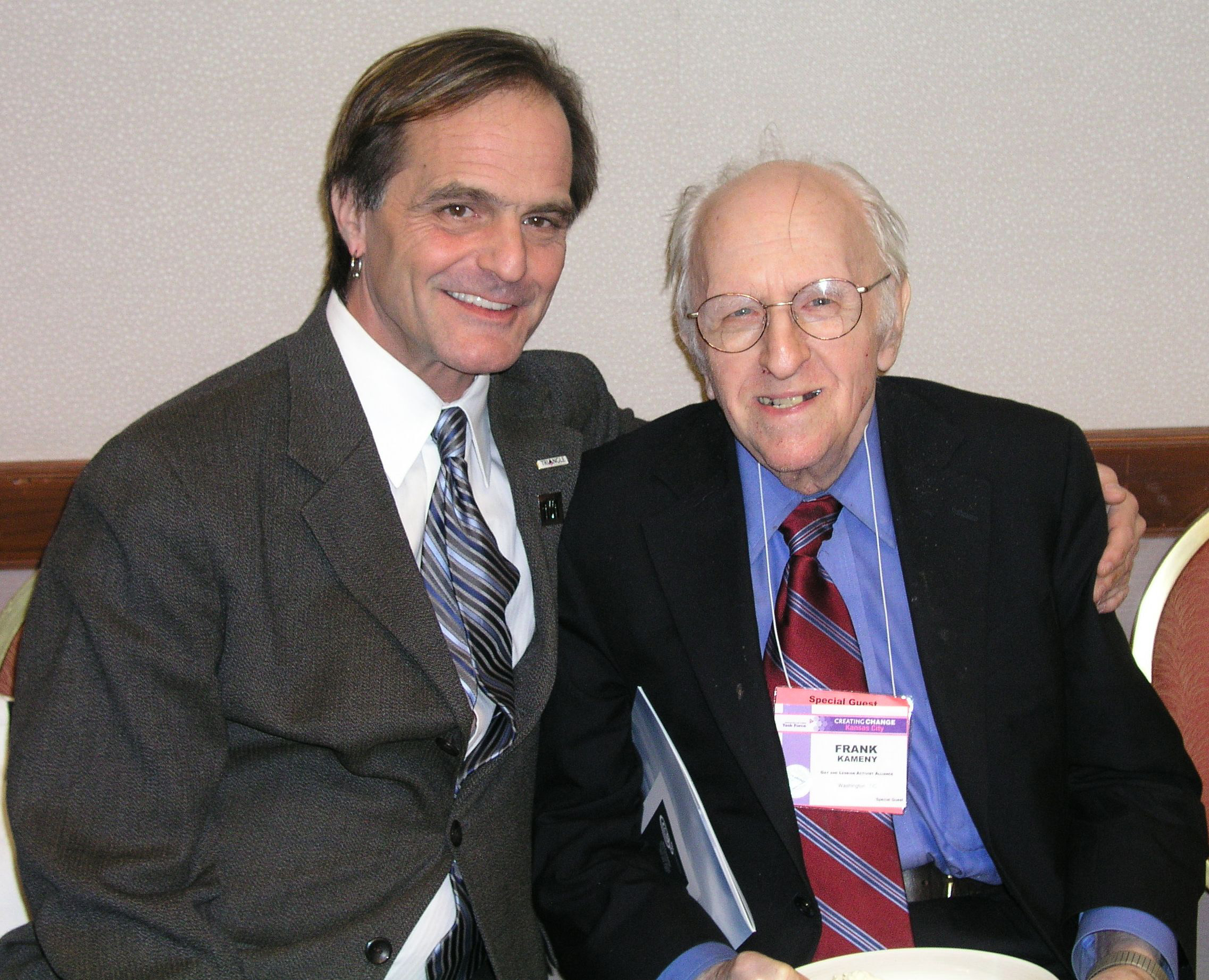

Jeff Montgomery with the late Frank Kamney at Creating Change in 2006. Photo: Ron Miotke

Jeff Montgomery with the late Frank Kamney at Creating Change in 2006. Photo: Ron MiotkeHe returned from East Lansing in the mid-70s and soon became a familiar face on television. His first crusade was to save the city's crumbling Orchestra Hall. There, he helped raise millions of dollars to restore the facility.

But in 1984 tragedy struck. A man he was dating – Michael – was shot to death outside a Detroit gay bar. The day after his funeral, Montgomery was informed by a friend in the prosecutor's office that he should not expect warrants or arrests in the murder. Why? The killing was "just another gay murder."

This launched Montgomery's passion to fighting anti-gay hate crimes and for the rights of LGBTQ people in Michigan and beyond.

In 1991, with John Monahan and Dr. Henry Messer, Montgomery set up shop for the Triangle Foundation – which he would lead until 2007. That organization merged with Michigan Equality to become Equality Michigan in 2010.

In a May 4, 2003 story in the Detroit News honoring Montgomery as a 2002 Michiganian of the Year, it noted he used his public relations skills combined with "a natural ability to connect with all kinds of people."

His national platform came from an odd murder case in Detroit. Scott Amedure, a 32-year-old Lake Orion gay man, appeared on the television tabloid talk show "The Jenny Jones Show," on March 6, 1995. On the show, Amedure revealed his crush on then 24-year-old Jonathon Schmitz. Once back in metro Detroit, and before the episode aired, Amedure left a "suggesstive note" on Schmitz home. Schmitz withdrew cash, purchased a shotgun, and showed up at Amedure's front door. The two talked, and the Schmitz walked back to his car, got the shotgun and returned to Amedure's door. He shot Amedure twice in the chest with the shotgun, left the scene, and called 911 to confess to the murder. He was subsequently convicted of second degree murder in 1996.

Montgomery's rational, thoughtful and oft-times witty interview skills won him kudos from national media as well as LGBTQ media advocates. Chief among those singing Montgomery's praises is Cathy Renna. She was with GLAAD at the time of the Amedure murder, and worked closely with him on interviews and messaging.

"He became the point person on that case and the expert on the gay panic defense," Renna said by phone.

That admiration Renna had for Montgomery led her to call him on what she refers to as the "most high profile anti-gay hate crime" in American history – the brutal robbery and murder of Matthew Shepard in October 1998. Shepard was lured from a Laramie, Wyoming bar in October 1998 by Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson. The two men then robbed him at gun point, tied him to a fence on a desolate hill outside of town and pistol whipped him. He died Oct. 12 of injuries sustained in the attack.

Henderson, Renna recalls, entered into a plea deal; but McKinney was planning for trial. He had, Renna said, set up a "gay panic defense," during interviews with detectives and was planning to use that defense in the trial.

"We saw what was looming with the trial of Aaron McKinney," she said. "We needed an expert and I called Jeff and asked him to come to Laramie."

Montgomery did just that. Renna said his presence and media skills "definitely influenced the media," by educating them about the double standard a gay panic defense represented. She credits that media work, in part, with turning the tide away from support for McKinney's claims and in the judge overseeing the case ultimately refusing to allow the defense.

Renna said Montgomery was "fearless," which aided in his capacity to be a good strategic thinker for the movement.

"He wasn't afraid to take on anyone," she said. "He wasn't afraid to take on anything."

Ricci Levy, executive director of the Woodhull Freedom Foundation – a group that advocates for sexual freedom – recalled a debate over marriage equality Montgomery participated in. During the debate, the opponent – Levy could not recall who it was – accused the LGBTQ movement of preparing the way for marriages with horses.

"I guess if that happened, it means I was in a stable relationship," she said Montgomery quipped.

Renna said behind the limelight persona, the leading voice on LGBTQ issues was a "renaissance thinker."

"He had a quest for knowledge," she said.

Colette Seguin Beighley, who worked for Triangle Foundation on the west side of Michigan, said his thirst for knowledge was evident even in his living conditions.

"He didn't cook," she said by Facebook chat. "So his kitchen cabinets were filled with books."

While Montgomery was finding success on the national stage and shaping LGBTQ message frames, he was also struggling with an addiction to alcohol. He was also a heavy smoker and constantly drinking black coffee.

"I met him for breakfast at the – the IHOP or whatever it was there in Laramie at the time – and he regaled me with the tales of his sexual exploits from cruising the night before," she said. "It was amazing, here he was in Laramie for this [hate crime] murder and he was cruising. He chain smoked and drank black coffee and told me all about it while he ate eggs sunnyside up – nearly raw really."

Renna said he was not just talking when he reminded the movement that the LGBTQ movement was about more than hate crimes laws, marriage and nondiscrimination. He reminded many that the work was rooted in the quest for sexual liberation.

"He was someone who understood this was about sexual liberation for everyone," she said. "We don't see enough of that in the movement."

Others who worked with him – Sean Kosofsky, who was policy director at Triangle and now runs the Tyler Clementi Foundation in New York, and Gregory Varnum, another former staffer at the organization – spoke of his mentorship.

"Last night, the LGBT movement, progressive movement, and indeed the world lost a living legend – and I lost a friend I have come to think of as family," Varnum wrote, in part, on his Facebook page.

Levy, from Woodhull Freedom Foundation where Montgomery served as a public relations consultant, as well as a board member, recalled he was always available for consultation.

"I knew I could call him," she said. "And he would know the answer."

Daniel Levy, legislative director for the Michigan Department of Civil Rights, said he had one over-arching image that dominated his imagination when he thought of Montgomery.

"I see someone standing on a mountaintop, with the wind blowing," Levy said. "And I see them holding the ground, maintaining the ground."

Plans are currently underway for a memorial service with details to follow.