How Queer Art Offers Freedom Where Freedom Isn't Always Found

The co-founders of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit on creative expression as activism

With Motor City Pride in Detroit — and Pride in cities throughout the country — queer festivals commemorate the fight for political equality accelerated by a demonstration, which began early in the morning of June 28, 1969, outside the Stonewall Inn, a Greenwich Village gay bar. Today, this demonstration is honored by annual June events worldwide. The social advances made since 1969 are celebrated. And the contributions of political activism are paid tribute. But is there an activism deeper than the Stonewall uprising and its fight against a night of police harassment and injustice?

There is the creation of a just culture. And this rests on art.

Art is a mirror. It shows. It reflects. It embodies self-recognition and affirms presence.

At the start of the 20th century, the queer presence — the “love that dared not speak its name” — was socially shunned, medically pathologized and legally criminalized. To be queer was to be an outsider in a manner deeper than politics. One ducked and steeled oneself alone or gathered in small rural or urban enclaves, stitched together like an Underground Railroad.

The exception was the world of art.

For queers, art offered a realm where you could confront and express yourself freely when all other opportunities were unavailable.

With art, you could embody or contemplate localities, relationships and social engagement — or protest the lack thereof. You could storm the barricades with banners and ideas — or engage with the intimate, the decorative, the erotic. You could envision communities, or a sphere of solitary reflection — or combinations of both. Art in all forms rendered our view of the universe concrete, including the scope of our possible action, long before the growth of social acceptance and political freedom. Art affirmed a world within reach.

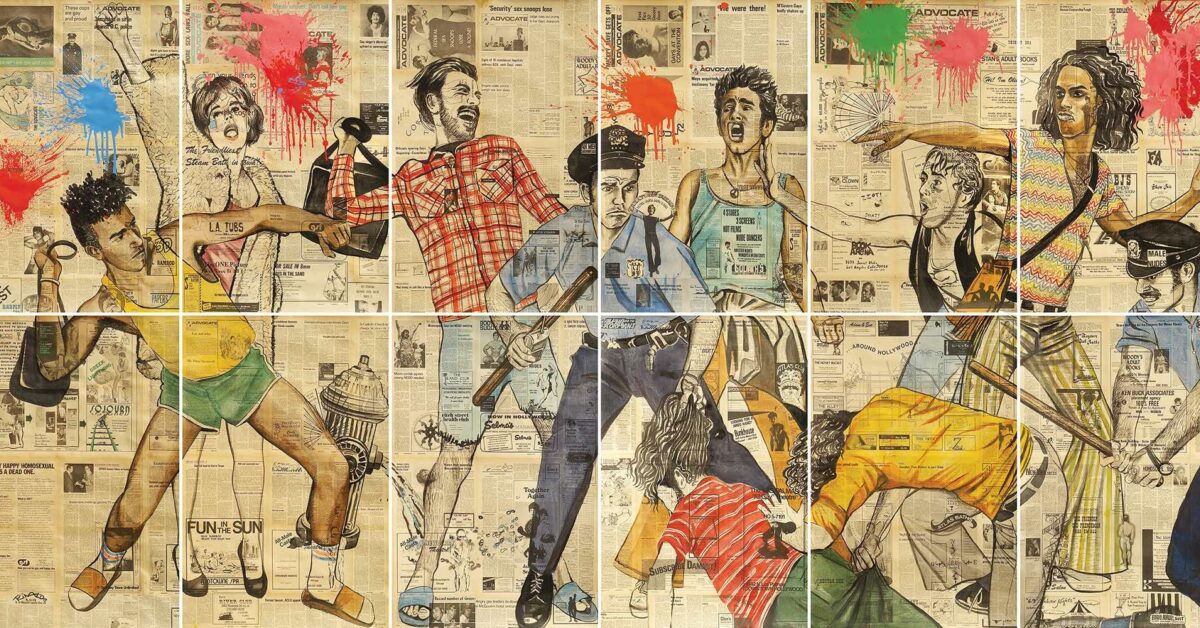

"I’ll Be Your Mirror: Reflections of the Contemporary Queer" assembles more than 800 such works by 170-plus artists in 11 galleries, revealing a range of identities and stories, from the playful to the political and the erotic to the domestic.

A selection of these works are displayed here:

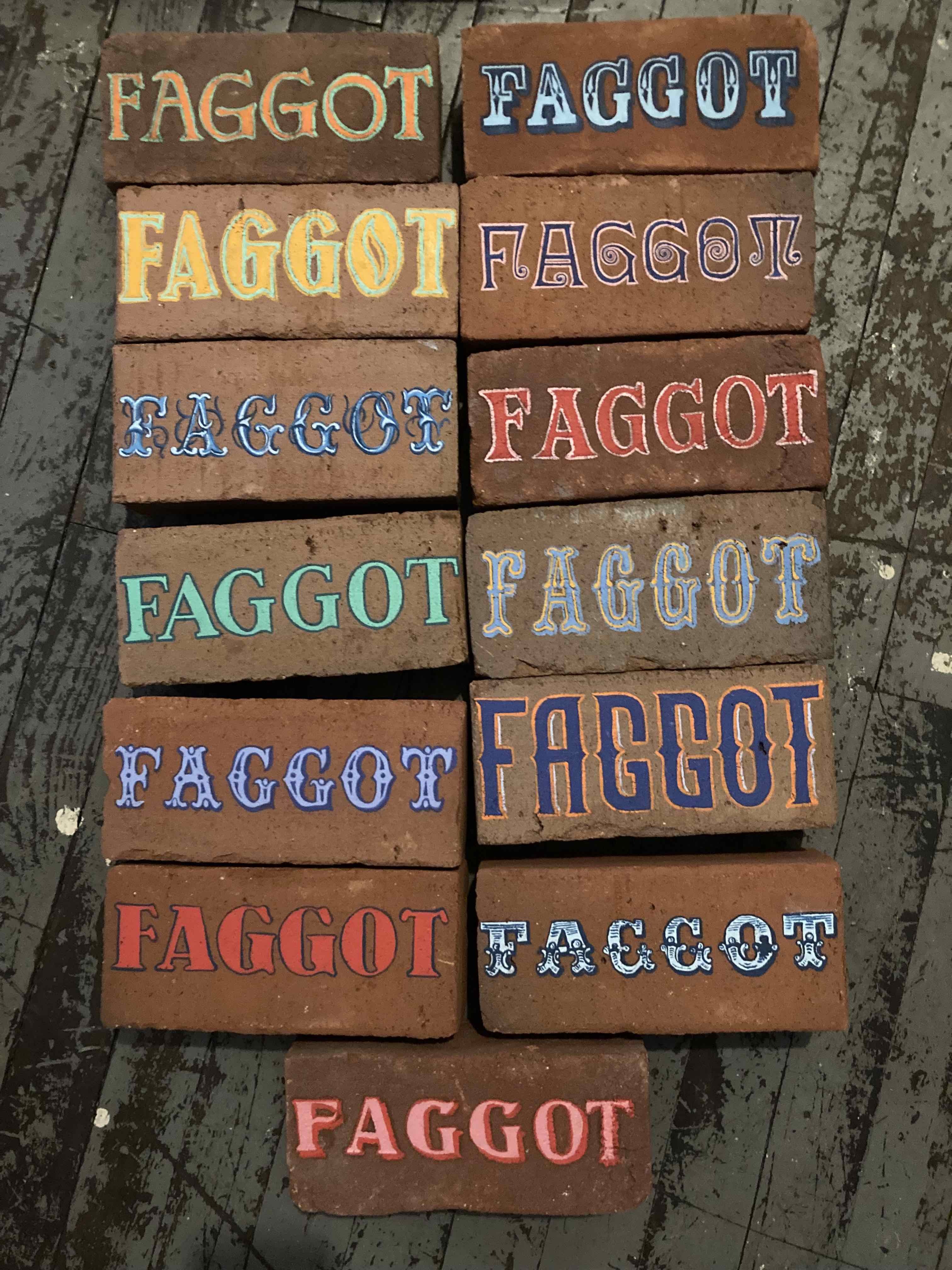

• Peter McGough’s painted brick is inspired by a verbal assault against the artist on the streets of New York City. In reference to Stonewall and the stoning of sinners, "Faggot Bricks" turns the name-calling of “faggot” inside out. Does the brick (or epithet) flung at you cause harm? Or is the brick a piece of the broken world you can pick up and rebuild?

• Felicita Felli Maynard’s "Ole Dandy, the Tribute," is a series of photographs that incorporate the historical perspective of a non-binary artist. Using vintage camerawork, Maynard references real figures to reimagine the life of a gender-expansive cabaret performer during the Harlem Renaissance.

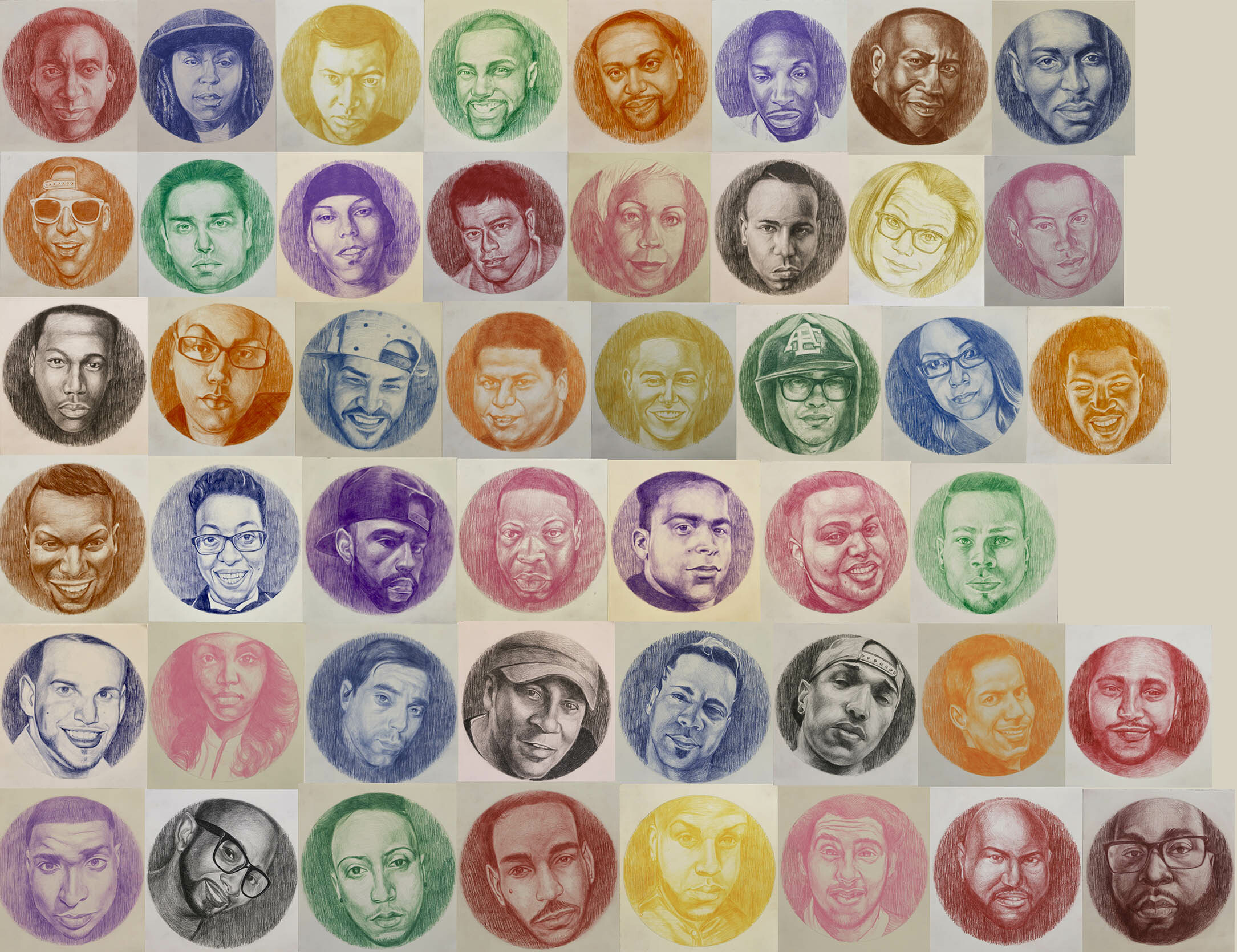

• Tylonn Sawyer’s work, "Forever Young: Pulse Night Club 49," memorializes the individuals who lost their lives in 2016 due to an act of domestic terrorism. This massacre, rooted in anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice, occurred in Orlando, Florida, during Pride Month. The 49 portraits are a unified piece, underscoring the scale of tragedy and the reality of grief.

• Eileen Mueller’s "Wayfinding," portrays trees adorned with trail marks or wayfinders. These markings use a code known to other queer women and reveal hidden paths to private glades, which offer a chance to engage in communal visibility and acceptance.

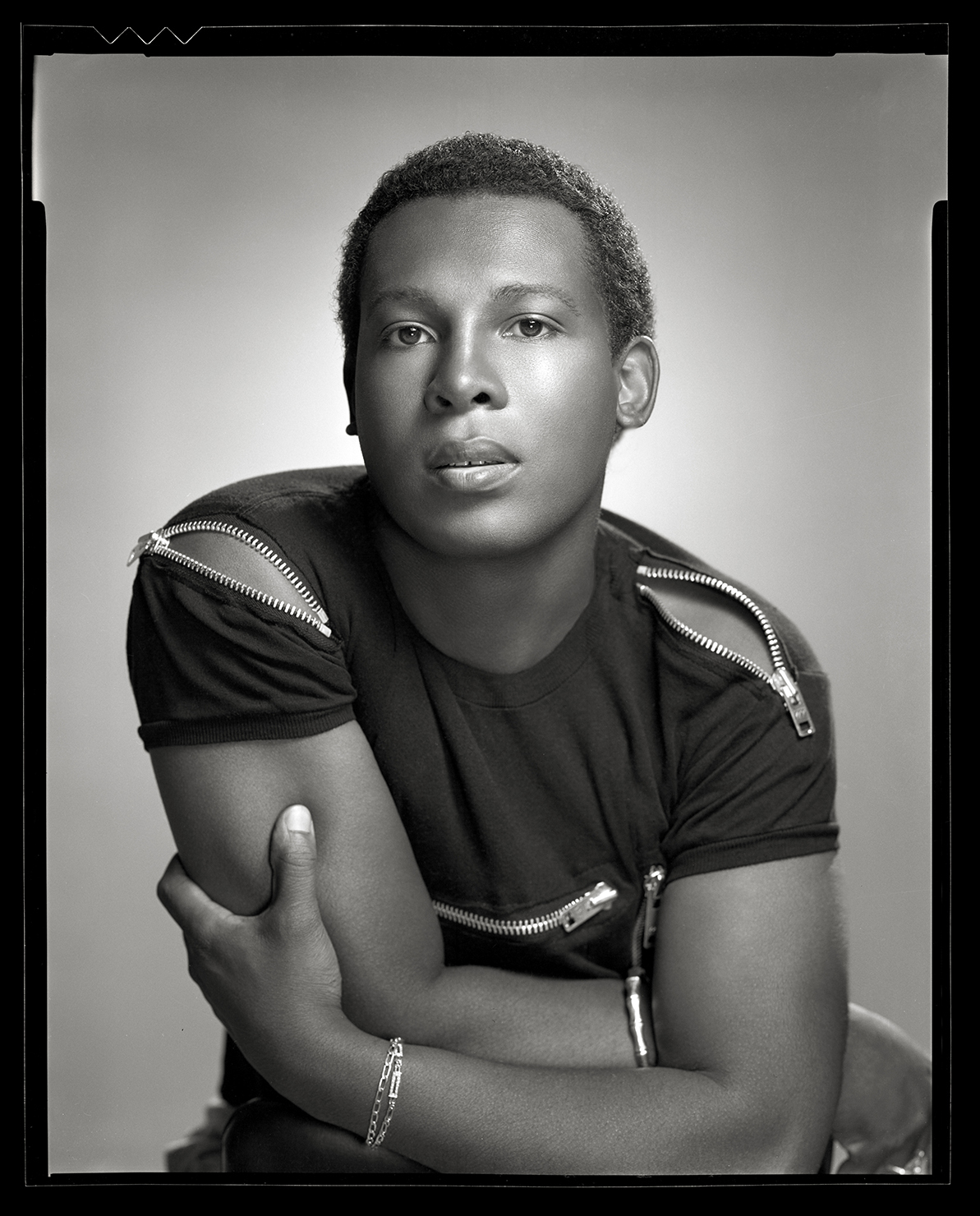

• Mark A. Vieira's 1979 "Portrait of Sylvester" captures the late singer in an image used by Fantasy Records without credit. Like many artists of old Hollywood, Vieira shapes a beautiful icon without recognition. Those who know Sylvester’s music can honor both the discothèque and Vieira’s recovery of authorship.

The art exhibited in "I’ll Be Your Mirror: Reflections of the Contemporary Queer" is a discovery: a dialogue of many voices, a discussion of what it means to be queer and non-queer — and, more so, what it means to be human.

The growing social acceptance of queers, now celebrated each June, was not achieved through legislation alone. The recognition of rights and their social protection is essential. And the details of politics are vital. But the experience of pride, afforded by standing before a mirror to confront one’s very self, is preliminary, whether that self is embodied in a painting, a poem, a film or music. The activism of art begins with recognizing and affirming the profoundly important. It starts with looking into the mirror, which is art — and returning to that mirror every day of one’s life.