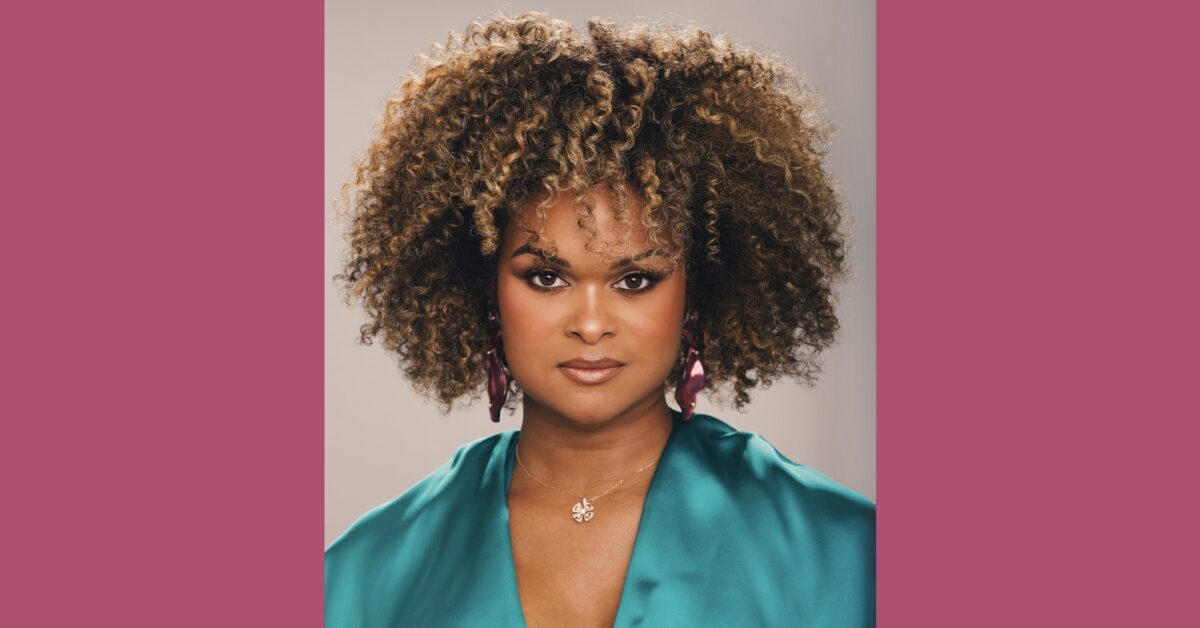

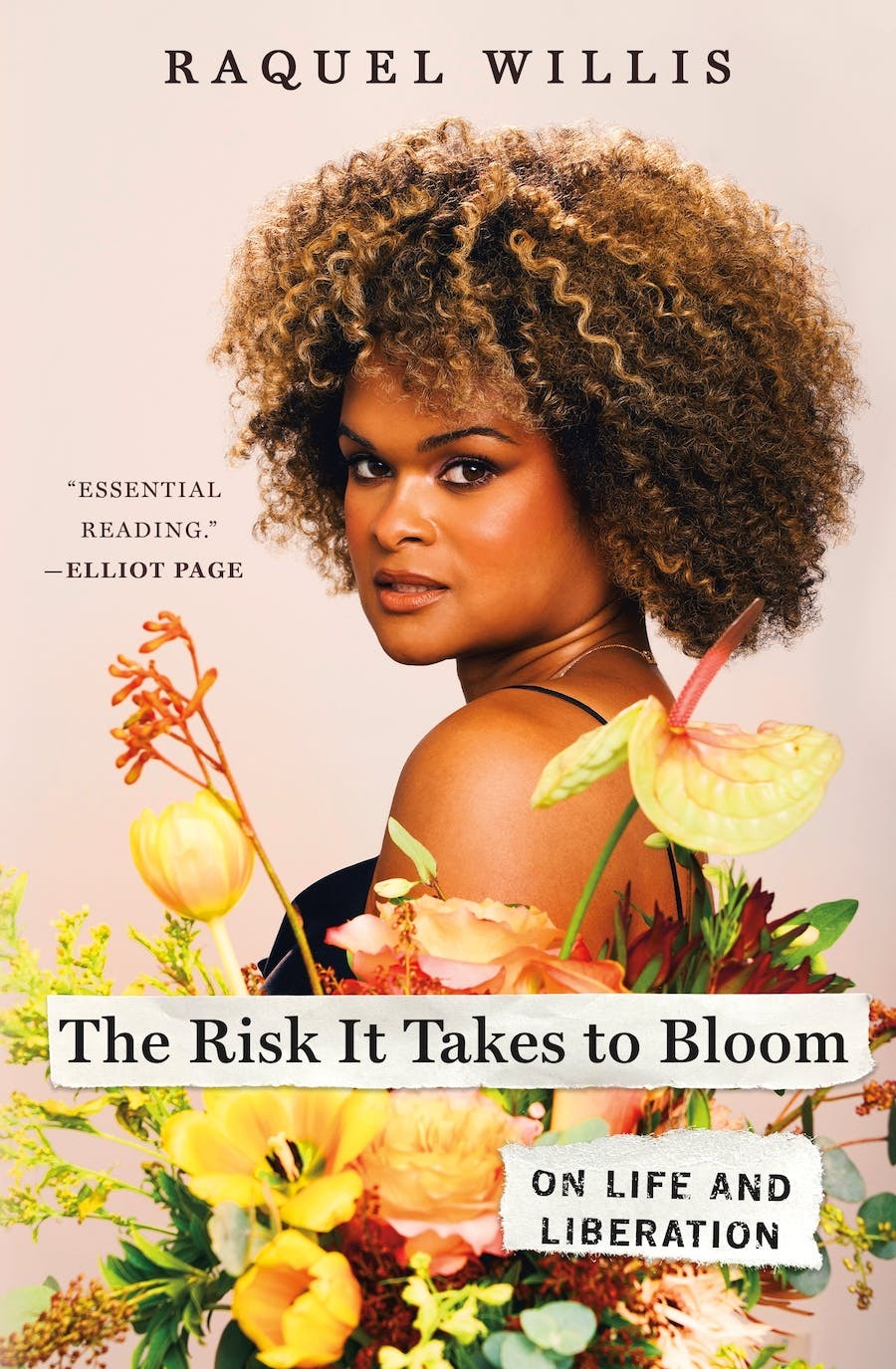

Black Trans Activist Raquel Willis on Why Stories Like Hers Need to Be Heard

'The Risk It Takes to Bloom' author on living a life of 'discomfort' and how she hopes to change that for others

When Raquel Willis took the stage at the National Women’s March in Washington, D.C. the day after Trump's inauguration in January 2017, with beaming defiance and fierce resolve, she didn’t sidestep the controversial way trans women had been sidelined from the planning of the momentous occasion. “Although I’m glad to be here now, it’s disheartening that women like me were an afterthought in the initial planning of this march,” she remarked. “Many of us had to stand a little taller to be heard, and that exclusion is nothing new.”

Willis has yet to let up the pressure on trans-exclusionary spaces and people since that cold winter day almost seven years ago. The Augusta, Georgia native details her life story and her ceaseless passion for advocacy in a candid new memoir, “The Risk It Takes to Bloom,” out Nov. 14. Raised Catholic in a Black Southern family, Willis explains how the death of her father when she was 19 contributed to years of grief, and ultimately, epiphanies about what she was meant to do with her life — how she began to truly bloom as a whole person.

Willis worked as a journalist during the early part of the Black Lives Matter movement, hiding her identity while working as a news reporter. Over time, she would publicly come out as transgender and become a powerful advocate. She served as director of communications for the Ms. Foundation for Women; as executive editor of Out magazine, where she started the award-winning Trans Obituaries Project, and as a national organizer for the Transgender Law Center. She writes about the reality of working in those “lofty” positions as a Black trans woman — experiences she says cast light on how progressive spaces can still contain systems of oppression. Willis is currently an executive producer for iHeartMedia’s LGBTQ+ Outspoken Podcast Network.

The activist sat down with Pride Source recently to discuss the new book, her continued advocacy and her thoughts about the current state of trans discrimination.

You write about your advocacy work during a pivotal time, where you started down this path during the Obama era, and then along came Trump and an abrupt anti-LGBTQ+ shift, politically and socially.

I would say things have certainly required us to have a bit more grace and nuance. And I don't necessarily mean that for our political figures — they are who they are; that is what that is. But I think living through the Trump era and being in the space where we are now, there's a lot of grace that I've had to have for myself around being able to hold those things that I have anxieties or insecurities about and then also being able to kind of push forward and also draw on my power.

We're living in a time of anti-trans discrimination, where being known makes us a target. I think many in the trans community want to be seen, but I think at this time, it's also at what cost? What are we willing to give up? What kind of risk, speaking to the title of the book, are we willing to take to be seen or to be heard?

We often have these kind of black and white ideas about which spaces are conservative and which spaces are progressive. And one thing that you will quickly realize, if you're on the margins within the margins, is that some of the spaces that we think may be the most progressive also have systems of oppression.

You touched on this in your speech at the Women’s March, before it was cut short.

Yes, this was seen as this kind of tent-pole feminist moment, but what did that mean for me as someone expecting that space to value my transness, to value my queerness in the same way that it was valuing this kind of feminist element of my activism?

And then later, for instance, I write about working at the Transgender Law Center. Working at this nonprofit that in many ways was the Holy Grail of where you would want to work as an empowered trans person. But again, still dealing with systems of oppression around anti-Blackness or dealing with misogynoir and maybe not hearing or maybe not experiencing being heard because of how hierarchy, and even capitalism, still kind of rips apart these progressive spaces on the margins at Out magazine.

I don't think that we have enough stories where it's a Black trans woman talking about her experience with her career, navigating the workplace in this way and also trying to maintain her values and dignity in those places. I also think about so many of the folks who had their first major social justice awakening during that summer of 2020 in the aftermath of the murders of George Floyd or Breonna Taylor and so many others. We're in this time where we're holding all of these truths and yearnings and desires and embodiments at once.

It's hard to understand that your perspective may just be one perspective. Usually, it's just one perspective and not the only one, and unfortunately, no matter how we come to our perspective, we still have to reckon with the fact that there are any number of them out there, especially if we're trying to work with others to create some kind of pathway to collective liberation.

No one wants to feel uncomfortable, but sometimes that’s what it takes, basically?

I think so much of the experience of folks on the margins is about that discomfort around being a trans person. My whole life has been about discomfort and not necessarily in the way that I think the average person may think.

So many folks paint the experience of being non-conforming or queer as some kind of internal discomfort. It's often, in my experience, not been so much about that internal discomfort. I think I've always had a feeling that I will be able to tease out whatever's happening internally in due time if I'm given the space and grace to, but it's that external discomfort that has often eaten up so much of my energy.

I dealt with peers at a young age who didn't understand why I was so feminine or the discomfort externally that I felt for my dad, who didn't understand who I was in so many different ways, or the discomfort I felt working, or when I was a student at the University of Georgia. Luckily, I found some LGBTQ+ community there, but I was still a Black student at a predominantly white institution and I was still the only openly trans woman student in that context in 2012, 2013.

So it’s that discomfort in those spaces or the discomfort of going to Out magazine and being the first trans woman to hold a leadership position at that publication. It has been a series of discomforts in this life of mine, but I think what I've learned from that is that those are opportunities to evolve not only for me but for the environment to evolve for the folks around me who are invested in something tangible and different.

Have you ever needed to compartmentalize some of this external pressure where people are constantly pointing out that you’re the first “this” or “that” when you’re really just trying to do your job some days?

I think at this point in my career, it can be comforting to understand the history, particularly trans history, and to know that there have been others who came before me. Maybe not exactly the same with the exact same credentials, but there have been trans storytellers before me. There have been trans folks trying to carve out a space in media before me. And so I can take comfort in knowing that wittingly or unwittingly, they did leave some bit of a broken pathway for me.

My hope is that whatever space I enter, I am carving out a container for the next folks to not have to check off as many boxes. My hope is to make it smoother for the next people. But also, everyone is carrying some kind of anxiety. It may seem more obvious about what mine may be, as a Black trans woman, but it doesn't do me any favors to forget that this white woman next to me has some anxieties, too, and probably some very similar ones. This dude over here has some anxieties, the straight person and the cisgender person. We have opportunities for connection by naming the insecurities, the anxieties and the awkwardnesses that exists, so we can be on the same page.

Are you noticing upcoming generations and their parents embracing topics like gender diversity and intersectionality?

It’s so interesting for me to see more and more parents who have young trans or nonconforming or queer or nonbinary people in their lives. And it's a beautiful thing that these shifts are happening, which is exactly why we see such dogged political attacks in this moment.

One of the throughlines for me and my activism work has been paying close attention to deaths that have happened, particularly in the trans community, and trying to turn the feelings those moments have elicited into activation. It was the suicide of 17-year-old Leelah Alcorn back in 2015 that really inspired me to speak up publicly for the first time about my transness because in my first role as a newspaper reporter in small-town Georgia, I was in the closet as a trans woman. I was not out professionally, and that was out of fear of losing my chance at a livelihood or a chance at starting a career.

And so when I was in my second job in Atlanta, Leelah’s death really pushed me to speak up, and I made this YouTube video, just talking about how it had impacted me. [After the BBC picked up the story], I had to come out to my co-workers, and luckily I was in a workplace that found that to be an empowering thing for me to do, but that was a shift.

You went on to focus much of your activism on the issue of violence against trans women of color. Why did you start the Trans Obituaries Project?

The Trans Obituaries project that I created in Out magazine was an opportunity for me to not only talk about this epidemic of violence but to also bring in a more investigative element like delving into the story of a 27-year-old Afro-Latina woman who died in Riker's custody named Layleen Polanco in 2019. Her story brought a different dynamic around someone who died in state custody and who was a sex worker who dealt with mental illness, who had epilepsy and was in ballroom culture in the House of Extravaganza. And so, she had all of these elements related to her whole life. I think that’s been at the heart of talking about this epidemic of violence for me — to get folks to remember that these people lived before they were taken.

I think we all kind of carry the lives of folks who have been taken, whether we were related to them, whether they were just in our community, or whether they shared some element of our identity or our experience. And I do feel like we have the opportunity to not just wallow in the grief and the mourning but to actually use whatever lane we're in to try and make things better so that doesn't happen again.

If you're in storytelling, you have the opportunity to uncover those stories or the dynamics that make those stories occur. If we're talking about education, you're in the educational system. You have to find a way to make sure that students don't feel the isolation that maybe someone like Leelah felt. There's so many opportunities here for that radical change. But we have to be endlessly curious and endlessly creative about how we can make those radical changes in our lives.