Nigerian Author Chukwuebuka Ibeh on Finding ‘Blessings’ in a Country Where Same-Sex Marriage (and Homosexuality) Is Outlawed

Banished to boarding school after getting caught by his father, a teenager forges his own path to self-acceptance

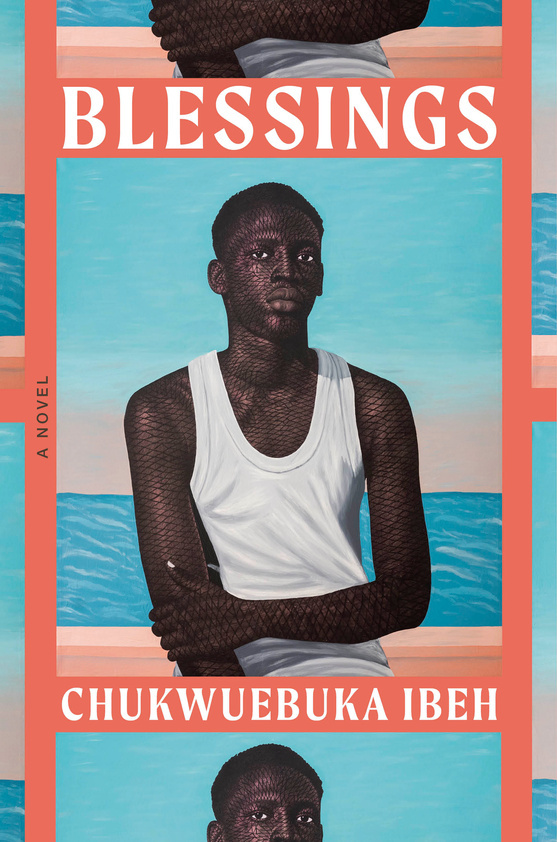

African novelist Chukwuebuka Ibeh tells the story of a queer boy struggling to define himself while seeking out affirmations in post-military Nigeria in his debut novel, “Blessings.” The book is set to publish June 4 via Doubleday, a Penguin Random House imprint. Already, USA Today has included it in their list of the Best Books by Black Authors to Read in 2024.

In the book, the powerful bildungsroman weaves in elements pulled from the real-life Nigerian political battle over marriage equality in that country, which enacted the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in 2014. The law further restricted the rights of LGBTQ+ people in a place where homosexual sex and same-sex organizations and businesses have been illegal for decades and where, as late as 2013, according to U.S. Pew Research Center, 98% of residents feel society should not accept homosexuality. Ibeh draws parallels between this legal context and the Obergefell v. Hodges decision that legalized same-sex marriage in the U.S. In some ways, he says, Nigeria’s same-sex marriage ban was a reaction to Obergefell.

“Blessings” is based partly on Ibeh’s experiences in a Christian boarding school in Nigeria, where he felt safer remaining mostly closeted. The book focuses on Obiefuna, a teen boy sent away to live in such a school after his father catches him being intimate with another boy. The school is strict and overwhelmingly conservative, but queerness is still a fact of life among the students, and there are blessings to be found along the long road toward self-acceptance.

Pride Source recently connected with Ibeh, named one of the “Most Promising New Voices of Nigerian Fiction” by Electric Lit, to learn more about how he explores the devastating impact of the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act against the backdrop of his coming-of-age novel and how he feels about the global state of LGBTQ+ culture and acceptance.

What can you tell readers about how the U.S. Supreme Court decision Obergefell vs. Hodges influenced the Nigerian government on the marriage equality front and how these legal moves influenced your book?

That’s a good question. I like to be clear that homophobia has never really been foreign to Nigerians — and it’s true that our earlier anti-gay laws were British colonial laws, but there’s a whole other context to that. I think, though, that part of the “effect,” so to speak, of the Supreme Court decision was an indication of too much liberal progress worldwide, which contrasted and alarmed a very religious, very conservative Nigeria. My guess is that Nigeria needed to send a message to the liberal West that it would not “allow its values to be corrupted.” It’s a stance I would otherwise find amusing for the irony, if it didn’t have actual victims.

The law, I think, was also part of a cynical political tactic by an increasingly unpopular government looking to score points with a conservative populace. These were among the things I wanted to explore in the novel, so I suppose “influence” is apt.

Your book focuses on Nigeria, but the story feels very universal — one that LGBTQ+ people anywhere can relate to on many levels. Would you agree with that assessment?

Yes, and thank you. I think all over the world, the liberal West included, queer people still don’t have full rights, still struggle with identity, acceptance — both self and external — and belonging. [They] are still more likely to be victims of targeted violence and hate crimes. It’s always curious for me to hear Nigerians say things like “go to America if you’re gay” as if America is an absolute paradise for gay people. That couldn’t be further from the truth.

On the other hand, readers outside Nigeria and Africa stand to learn so much about a culture that is quite unique in and of itself, as well. What are a few things about Nigerian culture you hope readers will take away?

I realize now that all boarding schools probably have similar structures and hierarchies, but I hoped to showcase the uniqueness of Nigerian religious boarding schools. And then there are other things that I think a lot of Nigerian Igbo families [a deeply rooted southeast Nigerian ethnicity and culture that emphasizes traditional family structures and conservative values] are obsessed about — the impact of naming, for instance.

Do you think things are getting better for LGBTQ+ people in 2024 in Nigeria? What about the U.S.?

Against my writerly instinct, my general outlook on life is one of an eternal optimist. So, regardless of the fact that the anti-gay laws are still in place and there have been no plans to reverse it, I still believe things are getting better. If only that Nigerians seem to be having open conversations about it — problematic sometimes, granted, but we’re talking, at the very least. It’s my hope that this novel drives even more conversations, and sparks more debates.

It also seems to me that there is an increase in queer visibility and open existence in Nigeria. It can’t be easy, obviously, especially for Nigerians based in Nigeria, but it’s admirable to see. In the U.S., however, I sometimes worry about a possible retrogression and that people are getting a bit too comfortable with bigotry in the guise of free speech. It’s particularly jarring in the U.S. because you’ve been made to believe it’s different here. In Nigeria, at least, you know early enough what to expect, and brace yourself ahead of time for the blow.