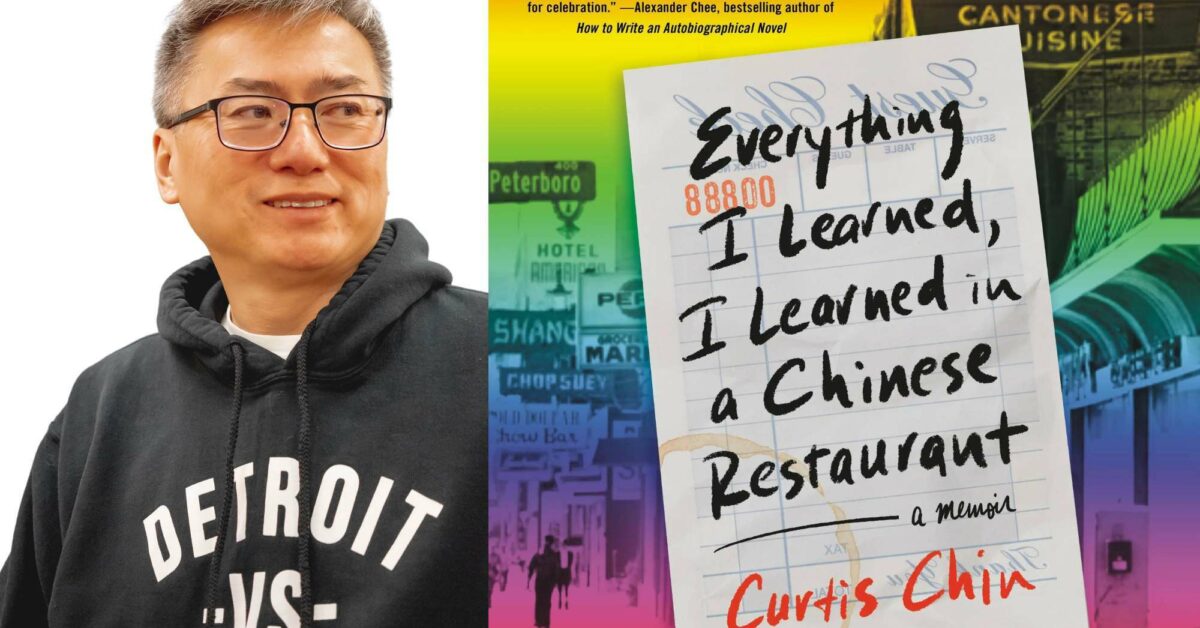

Detroit’s Chinatown Has Vanished, But This Queer Writer Keeps the Memories Alive in New Memoir

Curtis Chin on his journey growing up gay and Asian American during a pivotal, often violent Detroit era

In “Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant,” author Curtis Chin describes coming of age in Detroit’s Cass Corridor Chinatown neighborhood. In the ’70s and ’80s, his parents ran a popular Chinese restaurant (Chung’s, which was open from 1940-2000), where Chin spent many hours working while also absorbing the community around him, an experience that included coming to terms with his sexuality and navigating unique challenges related to his status as a Chinese-American child born to first-generation immigrant parents.

The Washington Post and Time magazine have declared the book a “must-read,” citing Chin’s candor and frequently humorous reflections on what was clearly a sometimes tumultuous upbringing. For all the light moments he recounts, the memoir is set against the backdrop of Detroit during his formative years, when the city saw far more everyday violence in working-class neighborhoods like Chin’s than we see now — by 18, he’d known five people who had been murdered. Still, “Everything I Learned” is a “love letter to my hometown,” Chin says.

“They’re going to learn about an Asian American family, but in actuality, they’re going to learn about Detroit — and also America — at that time period,” he tells Pride Source. “A lot of the issues we deal with now, we see the origins from that era.”

Hearing Chin describe his growing-up era, which was primarily the 1980s, can feel a bit unsettling. For him, it was “just normal that people would die around you and that buildings would burn down around you, so I don’t have another frame of reference. I mean, you’re a kid. I didn’t necessarily stress out about it.”

Throughout the book, Chin touches on stories that will resonate with Michiganders who experienced life in Detroit in the ’80s, which he describes as a pivotal time period for the city. Chin reflects on Detroit’s first Black mayor, Coleman Young, who served the city for two decades in that role, for better or worse, depending on who you ask. He also dives into what it was like to be part of an Asian American family when news broke about Vincent Chin, a Chinese American Detroiter who was killed in 1982 in a racially motivated attack by two white autoworkers who received no jail time for the crime. “If you grew up in Detroit in the ’80s, you’ll be able to relate to the book so much — even if you’re not gay, even if you’re not Asian,” he says. “The book is really for Detroiters from the ’80s, just through the prism of an Asian boy.”

As Chin’s story unfolds, he writes about the growing realization that he was not straight. While it was more taboo in the ’80s, and especially among the Asian American community, Chin recalls there being a gay community in Detroit’s Chinatown; he names the gay bar the Gold Dollar (where the White Stripes got their start after it became a rock bar) and says there were several prominently owned LGBTQ+ businesses. Chin mentions that while he didn’t set out to focus on his sexuality in the book, he recognizes it’s been important to LGBTQ+ readers to see themselves reflected.

“I really didn’t think about it because I was just trying to tell my own story. I’m not trying to represent anybody — just my own truth, but now that the book’s done, I do recognize that it does have that impact,” he says before describing an encounter with an Asian American lesbian on a recent visit home to Detroit for a book reading.

“She came up to me, excited about the reading, and she’s invited her parents to come, as well as the parents of her girlfriend, who’s also Asian, and she was saying how none of the parents were accepting or happy about the relationship, but were excited to come to the book reading,” he recalls. “She thinks of it as an opportunity to maybe start a conversation or to also show her parents that being gay can be something that could be celebrated, something positive in our community. And when I think about that, I think, ‘Wow, that’s really great.’”

Chin feels many young LGBTQ+ people today don’t realize what it was like to come out in an era like the ’80s, when, he says, it could feel like a death sentence. “For older people like me, we still remember those time periods when gays were not accepted, when you could lose your job because of your sexual orientation or go to jail,” he says. “I think the way that we’re processing some of the stuff happening today might be different from the way [younger people] are. It could be good for them to read this and see that perspective.”

At certain points, Chin remembers, he assumed he’d never make it to the age of 30 because dying from AIDS seemed inevitable. “I did not see myself having a very long life — it’s a driving point in the book because I didn’t want to go to college because I didn’t understand the point of sitting in a classroom for four years when I would probably be dead by the next decade.”

Ultimately, Chin did attend college at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor after deciding that four years wasn’t actually a lot, given that his parents had sacrificed their “whole lives” for their children. Since then, he’s established a career based in New York City, where he co-founded the Asian American Writers’ Workshop; in Hollywood, he’s spent years writing for network and cable television and writing and directing social justice documentaries. An essay he wrote that appeared in Bon Appetit magazine, “Detroit’s Chinatown and Gayborhood Felt Like Two Separate Worlds. Then They Collided,” was selected for the Best Food Writing in America 2023 award.

Looking ahead, Chin isn’t sure what will — or should — happen to Detroit, especially now that the heart of what was once a thriving Chinatown community is effectively gone. Recently, the city opted to tear down a community center that had stood in the neighborhood for decades, discarding a unanimous city council vote in favor of halting the demolition for 30 days so a study could be conducted to determine if the building had historical value. “You’d think they would want to respect that history a little bit more, so that part makes me a little sad, but I don’t know,” he says. “I mean, I do want this city to move forward, but I don’t want them to completely forget the past.”

In the meantime, Chin will keep memories alive of a childhood in Detroit that he says he wouldn’t trade for “anything in the world.”

Visit curtisfromdetroit.com for details about Chin's book tour, which will visit Southeast Michigan in early November.