Did Southeast Michigan’s LGBTQ+ Community Fail Fallen Leader as New Doc Alleges?

Sorting out LGBTQ+ activist Jeff Montgomery’s sometimes troubled legacy

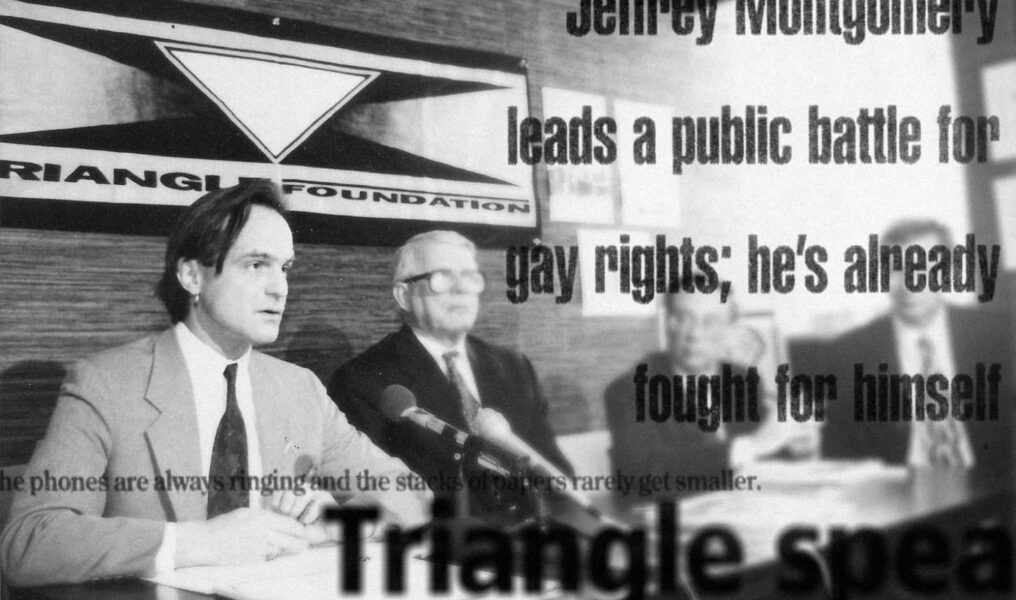

There is a lot to be gleaned from the new Jeffrey Montgomery documentary “America, You Kill Me.” Viewers learn of his early days, the death of his lover, the creation of the Detroit-based Triangle Foundation and Montgomery’s many years at the forefront in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. But the documentary also depicts Montgomery’s fall from grace and talks about when, after being sober for nearly two decades, he fell off the wagon and left the agency he helped build in disgrace.

In the film, some of Montgomery’s closest friends and associates allege that the LGBTQ+ community abandoned the fallen leader at this time. In the years after his departure from Triangle, Montgomery endured — in addition to his quest to regain sobriety — long term health problems (he had polyarteritis nodosa, a painful necrotizing inflammation of blood vessels), eviction from his home and the nagging sense that he had been forgotten.

“We had really drained as much out of him as we possibly could, and then we weren’t particularly interested in taking care of him after that,” former Triangle staff member Greg Varnum says in the film. “And, I think, it’s probably the most shameful thing our movement has done.”

James Lessenberry, Montgomery’s friend and longtime Triangle board member, even takes it a step further, accusing Dr. Henry Messer, Triangle co-founder and a mentor to Montgomery, of turning his back on the man he chose to lead the agency.

“Henry abandoned him, both personally and professionally, and worked very actively to have him removed from the organization,” Lessenberry says.

These are allegations that have hitherto now not been discussed or journalistically examined. Did Michigan’s LGBTQ+ community fail to honor its debt to Montgomery in his final years? Should he have been better taken care of, more looked after or, simply, more revered?

Montgomery, Messer and John Monahan are credited as being the three co-founders of Triangle. Messer was especially important to the creation of the agency. A brain surgeon, Messer had the money and connections to get Triangle off the ground. For many years, Messer was Montgomery’s biggest fan. But after 16 years of working together, Messer grew to have no tolerance for Montgomery’s drinking.

“Henry didn’t understand alcoholism as a disease,” John Montgomery, Jeff’s brother and a producer of the film, tells Pride Source. “He thought it more of a weakness. And he didn’t want to be involved in any part of that.”

Once he was out at Triangle, Montgomery, according to the film, became something of a pariah in the community. “He would reach out to people and often they wouldn’t call him back,” says Ricci Levy of the Woodhull Freedom Foundation in the film. “And that hurt him. He was a really sensitive person, and he knew it was personal, and he knew he had screwed up and he just couldn’t figure out how to get his credibility back.”

In 2014, seven years after resigning his post at Triangle, Montgomery said in the film he was invited back to tour the old office, known since 2010 as Equality Michigan. But after being invited, the film says, Montgomery’s phone calls to make plans for the visit went unreturned for six months.

Finally, Montgomery announces a visit and sets a time with current agency staff. One minute prior to the time of the meeting, then Equality Michigan Executive Director Emily Dievendorf texts Montgomery to say she won’t be in the office. The staff member who eventually lets Montgomery into the building does not even know who he is.

Sean Kosofsky was Triangle’s director of policy and Montgomery’s number two man. It was he who confronted Montgomery about his drinking. When Montgomery confirmed he’d been back to drinking for almost the past year, Kosofsky knew the agency had a problem.

“Jeff was my boss and my best friend,” Kosofsky tells Pride Source. “I didn’t know anything about alcoholism. But I did know that this was going to be a big problem.”

As the depth of Montgomery’s issues came to the fore, the agency’s board and staff fell into two different camps. There were those who just wanted to get him dried out and to protect him. Then there were those who felt he was damaging Triangle’s reputation and had to go.

“I believe Henry was in the camp of ‘Jeff needs recovery, not just to be dry,’” says Kosofsky, who actually attended Al-Anon meetings to better understand what had happened with the Montgomery situation. “He was financing a lot of the organization. Henry was a pretty sizable donor and he felt he needed to have confidence in the leadership.”

Having diametrically opposed camps at the organization made things difficult, but Montgomery’s drinking was always the root of the problem. “One thing I learned from Al-Anon is you can’t make an alcoholic not drink,” Kosofsky says. “They have to want to. And Jeff’s own alcoholic behavior pushed people away.”

Kosofsky said that everyone was trying to support Montgomery in any way that they could. Triangle, he said, basically paid Montgomery to try to dry out for two years before he ultimately left.

“The movement was willing to walk away from Jeff, but those of us on the inside were trying to help in our way. James, Henry, everyone was trying to do what, within our tools, was the best thing to do to make our hero better. It was very painful.”

When Montgomery died in 2016, at age 63, he was regaled at his memorial service, attended by 150 people, as a pioneer and a legend. Nothing was said of his fall from grace, only of his triumphs. Today, Equality Michigan Executive Director Erin Knott says Montgomery’s picture hung in the office until the building was sold last year.

“I think that we wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for his legacy and the work that he did on behalf of the community,” Knott says. “He founded Equality Michigan and he put his blood, sweat and tears into helping victims, and today we have a department of victim services that is still doing the work that he started.”