Do We Still Need Gay Bars? This Author’s Book Tackles Why They’re Dying — and Why We Shouldn’t Let Them

Greggor Mattson traveled to 39 states to write his new book on our endangered queer bar spaces

When The Woodward caught fire and subsequently closed in 2022, Metro Detroit lost not only a central gathering place for LGBTQ+ residents, but a crucial site of queer history. But even if it hadn’t come to an untimely demise, its status as a bar that catered to a primarily Black clientele was always endangered.

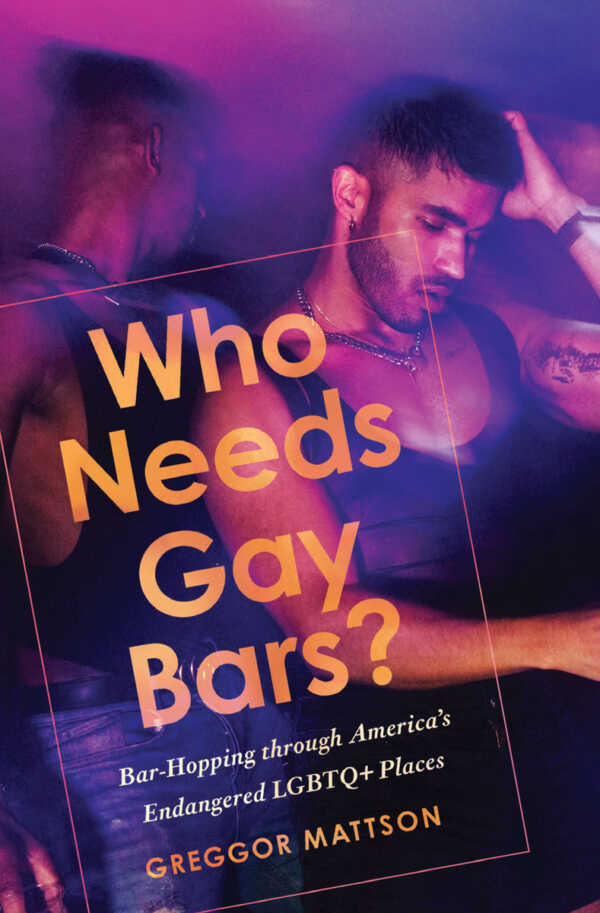

“The fastest declining types of gay bars have been bars serving people of color and bars serving men’s kink communities,” says Greggor Mattson, an Oberlin College professor and author of “Who Needs Gay Bars? Bar-Hopping Through America’s Endangered LGBTQ+ Places.”

One could also point to the former R&R Saloon, a leather bar in Southwest Detroit that closed in the 2010s and has had some false starts of revival since. Is it that Detroit doesn’t have room for these kinds of bars, or is there something to be said at large about gay bars?

Mattson tackles the latter question in his book, in which he details hitting the road across America — 39 states and 10,000 miles on his car — and visiting every gay bar he could. Small towns. Midsize metros. Big cities. Mattson noticed at least one commonality everywhere: Every bar was vital to the queer community because it was their community, particularly in smaller places where being out isn’t always tolerated.

But Mattson also noticed that gay bars varied across how they treated patrons of color, how they treated older gay men and how they treated straight patrons. Some — like The Woodward, which Mattson cites as a standout gay bar — do well with race and other identifiers, but many don’t take into consideration anyone other than “white, cisgender, middle-class men,” Mattson says.

“I think owners are increasingly recognizing that they need all of us in order to survive financially, and I think it’s incumbent on those of us in the community with privilege to encourage our owners and staff to look around the room and see how we can make this place represent all of us, and be there for all of us,” Mattson says.

That’s why places like The Woodward were crucial, Mattson said, because it was a safe space for Black gay men. Mattson, who is white, details a story in one chapter about how he and his partner, who is Black, were out at a gay bar in northeastern Ohio. It’s one of the few places that Mattson feels comfortable as a “middle-aged” gay, but “some of the old, white, cis guys are creeps” when it comes to his partner.

“Who Needs Gay Bars?” wrestles with that conundrum and other paradoxes throughout the book. On one hand, gay bars are a necessity because of their historic role as sites for organizing the fight for civil rights and their role as fundraisers for various marginalized communities beyond their own. But Mattson also calls into question who is responsible for the slowly declining number of gay bars.

If kink bars are disappearing, Mattson argues, some of that can be attributed to intra-community judgment of those who don’t fit a more heteronormative — and socially acceptable — ideal of queerness.

“Today when people say that there’s too much kink in bars or too much kink at Pride, they are part of a long but ultimately losing tradition of trying to boundary keep who gets to be in the community and who gets to be deemed respectable,” Mattson said, noting that in his research he found fewer than 60 “back rooms,” bear bars and kink bars open across the entire country.

Kink or no, all interactions at gay bars must be treated with respect. A realization during his research was that Mattson was violated in several ways while frequenting gay bars, as the bar for consent around touching has shifted in recent years.

“The number of times that someone has tweaked my nipple and it has caused pain have been many, and it really was from my students that they were like, ‘That’s nonconsensual.’ I was like, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa, isn’t that putting too heavy a word on it?’ But no, we can teach consent in small ways.”

Gay bars can get to their North Star, Mattson says, by remembering their roles as not just providers of safe spaces, but by understanding how money flows through the community. As many readers might learn as they read Mattson, “the fetish and kink community is probably the second largest fundraising part of our community in terms of raising money for charities.” That’s second only to drag queens, who Mattson notes are unsung heroines in their role in getting people to pony up.

In some cities, gay bars are embedded enough into the community at large where fundraising can go beyond LGBTQ+ concerns. Should they be lost, a well of funding for causes would dry up and drag queens would be out of a job.

As Mattson was writing, drag queens have already been mainstreamed outside the queer community, and this factors into the finished product. But he didn’t foresee the current attacks on drag-themed events or critics referring to them and trans individuals as groomers.

“One of the most significant things about the attacks on drag and trans people is that it’s happening at a time of unprecedented visibility. They’re targeting the fact that drag and transness is now everywhere, and they’re trying to put the genie back into the bottle — and it’s not gonna work.”

That’s where gay bars are positioned to become places of activism in addition to entertainment. The Stonewall Inn in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village is, of course, the granddaddy of queer civil rights sites. In the decades since, gay bars across America have continued to be on the front lines of the fight, which is sometimes just a fight to exist.

“What activism looks like is very different in a small town in Texas or Indiana than it is in a big city like Detroit or Los Angeles. So in some of these smaller cities, just merely being an open place is radical, providing a place for LGBTQ folks to gather together,” Mattson says.

One could argue that gay bars aren’t needed anymore as acceptance has become more widespread on topics like the ballroom movement, drag going mainstream, gay marriage being upheld, the rise of gay apps and straight people becoming better allies. Maybe gays should just start bringing their boyfriends and friend groups to straight bars, the argument goes.

It’s an argument Mattson is ready to have.

“I wonder whether straight places will be as resolute in the face of political attacks, whether they have the resources to do that, and I also wonder whether they are able to cater to the breadth and depth of our community,” Mattson says. “It’s dangerous to over idealize gay bars because they haven’t always included all of us, and at the end of the day they are small businesses that need to pay their bills. But it’s equally dangerous to dismiss them, given the important and life-saving role they play for so many of us at some point in our lives.”