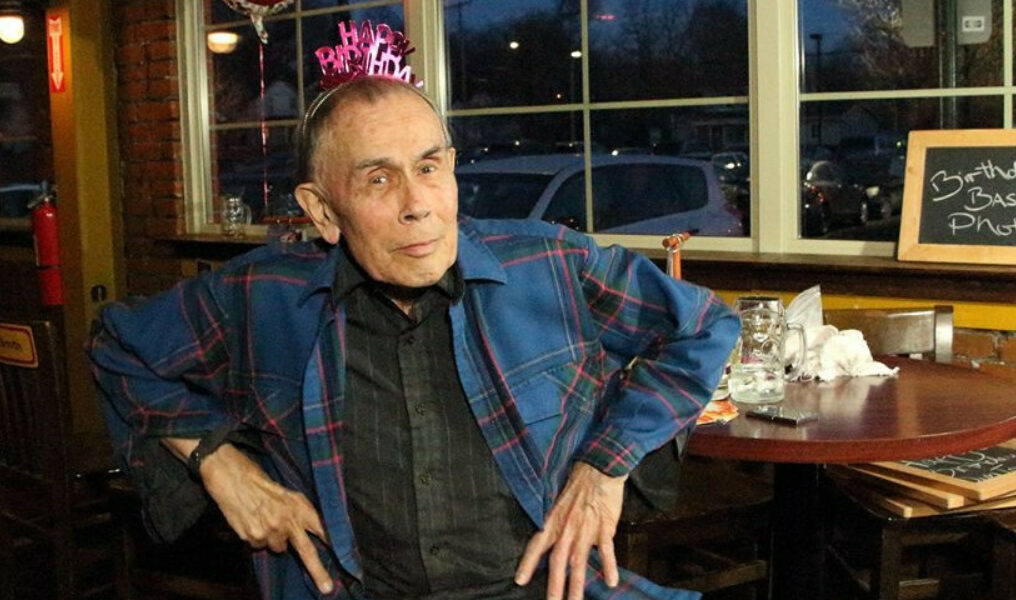

Gentlest But Most Unshakeable Campaigner' Jim Toy, Michigan LGBTQ+ Trailblazer and Icon, Dies at 91

On April 15, 1970, at a large demonstration held in Kennedy Square in downtown Detroit to protest the war in Vietnam, Jim Toy became perhaps the first person in Michigan to publicly come out as gay.

A year-and-a-half later, Toy co-founded what was then called the Human Sexuality Office at the University of Michigan, the first campus office in the United States that aimed to serve those we’ve come to call lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer.

At a time when LGBTQ+ people faced harsh attacks to their very being from legal, psychiatric, religious and educational authorities, Toy set an example for others to resist social animus, live honestly, and pursue justice. His life’s work continued in the decades that followed.

Jim Toy, tireless activist, advocate and gay force to be reckoned with for more than half a century, died on New Year’s Day at the Hillside Terrace Retirement Community in Ann Arbor.

He was 91 and had been living with dementia and declining health for many months. His close friend and caretaker Scott Dennis was at his side shortly before he passed.

Former Jim Toy Community Center board member Kerene Moore announced the news on one of Toy’s two Facebook pages.

James Willis Toy was born April 29, 1930 in New York City to James Toy and the former Imogen Hamblen. His mother, a missionary teacher of Scotch-Irish descent born in Japan, died soon after childbirth. His father, a World War I veteran of Chinese descent, worked as a chemist and had once been on a research team for famed inventor Thomas Edison, only to be fired when he and other assistants attempted to concoct some home brew in Edison’s laboratory.

In the early 1930s, young Toy moved in with his maternal grandparents in the small town of Granville in rural Ohio, 30 miles northeast of Columbus. During a TED Talk at the University of Michigan in 2012, Toy recounted growing up on a farm, joking that they had only candles and kerosine lamps. His father soon remarried and moved to Granville as well.

According to a biography Toy provided to the LGBTQ Religious Archives Network, the entry of the U.S. into World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor brought him face-to-face with racist harassment from high school classmates who responded negatively to his Chinese-American heritage. To protect himself from assault, he was compelled to don a cardboard placard around his neck to proclaim he was not Japanese.

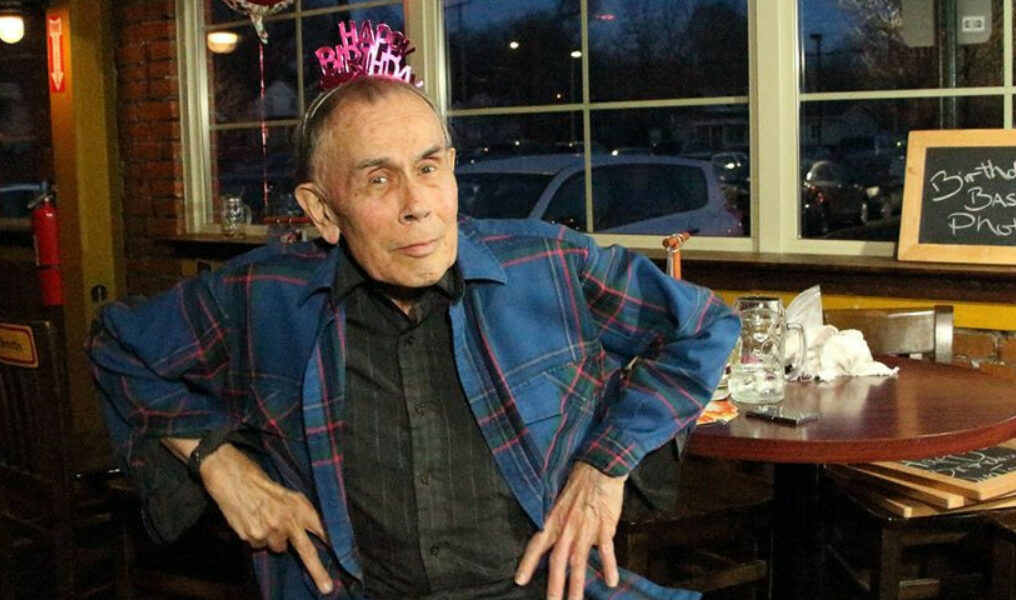

Toy excelled in his studies, graduating with the class of 1947 from Granville High School and being named valedictorian after a year at Licking County Joint Vocational School. He went on to earn his B.A. in Music and French in 1951 from Denison University, where one of his classmates was actor Hal Holbrook.

After a stint teaching high school English in France for the French National Government, Toy worked as a clerk for a hospital blood bank in New York City. The job fulfilled his alternate service requirement as a conscientious objector in lieu of serving in the U.S. military.

It was in New York that Toy faced inklings that he might be homosexual. “Growing up in a time when sexual orientation was not discussed, I felt confusion, isolation, shame, despair,” he told Between The Lines, Pride Source’s print publication, in 1998. “I didn’t know that I was anything but a suicidally unhappy heterosexual person. A gay man in Manhattan took me under his wing and began helping me understand that I was in a closet.”

In 1957, Toy moved to Detroit to take a job as organist and choir leader for St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church. A year later he became heterosexually married to a woman named Janet.

They divorced after seven years, though remained friends.

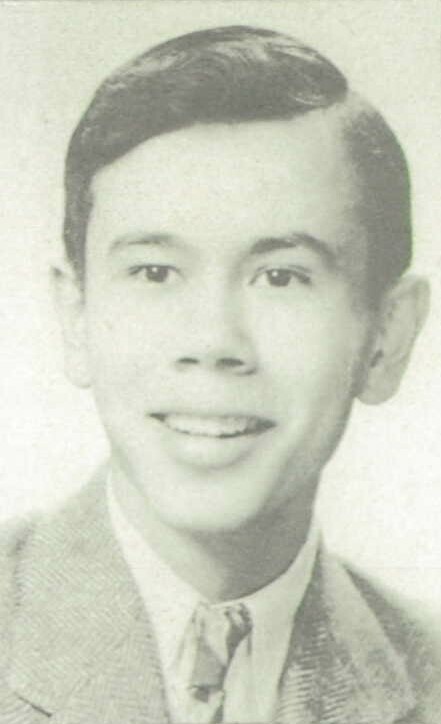

Toy enrolled in the School of Music at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in 1960 to pursue a Ph.D. in musicology. He formally achieved candidacy in 1970 but did not complete the degree. “It was clear I had no vocation to continue a musicology program,” he said in a WRAP newsletter profile in 2005.

He earned his Master’s in Clinical Social Work in 1981.

Retired librarian James Kangas met Toy not long after Kangas started at the Music School in 1966. At first somewhat casual friends, their friendship grew over time even when Kangas moved to Chicago and later to Flint. The two bonded over music and culture, attending University Musical Society concerts, playing together in a chamber music quartet with Toy on violin, and traveling to Stratford, Ontario to see plays.

“He was very possibly the most brilliant man I’ve ever known and a great eccentric,” Kangas shared in with Pride Source. Kangas got to know a more intimate, playful side of Toy, albeit still guarded. “He would crack witticisms, as it were,” Kangas said.

Most people, however, knew only Toy’s public side and that public side emerged from his longtime activism.

As Toy often observed, the 1960s were “radical times” and he was deeply influenced by the multiple movements that emerged from the social tumult.

Six months after the 1969 Stonewall Uprising in New York, while typing the church bulletin, Toy learned about a “gay meeting” to be held at St. Joseph in January 1970. Toy attended the initial meeting of the Detroit Gay Liberation Front and volunteered to serve as its secretary.

That March, he became a founder of the Ann Arbor Gay Liberation Front.

A month later he spoke on behalf of GLF in solidarity with the burgeoning anti-war movement at a large rally in Detroit. According to FBI surveillance documents and Detroit Red Squad files released through the Freedom of Information Act, some of the organizers resisted allowing a gay speaker, but GLF persisted and so prevailed in being included in the program.

“I can remember that being a very scary experience for me. I can remember being hot, literally hot and cold at the same time,” Jim remembered in a 1994 oral history interview.

“But I got up there and said what I had to say.”

As recorded in a surviving draft of the speech, Toy called on gay people to “join in the struggle to end this war.” He urged the others gathered to “put an end to sexual chauvinism and to support our movement for gay liberation.”

Toy called attention to linkages between sexual and gender freedom and other fights for social justice. He also challenged the hiddenness and silence that defined so much of queer life up to that time. When most of society still considered homosexuality criminal, sinful and sick, the speech was an act of courage, and it marked a major turning point for gay visibility in Michigan.

In the ensuing months, Toy and other Gay Lib activists challenged some of the highest echelons of society. The Ann Arbor GLF demonstrated against UM president Robben Fleming in June 1970 for refusing to permit use of campus buildings for a gay student conference.

Then, after Bishop Richard Emrich evicted the Detroit GLF from St. Joseph’s, activists disrupted the annual Episcopal Diocesan convention in November 1970. Toy was denied an opportunity to speak to the assembly as Emrich gaveled the meeting to an early close. However controversial, GLF's actions may nonetheless have impacted Emrich because the bishop subsequently appointed Toy a founding member of the Diocesan Commission on Homosexuality, a group that went on to issue a landmark 1973 report, one of the earliest U.S. church documents in support of queer people.

In November 1971, members of the Ann Arbor GLF pressed the UM Office of Student Services to hire paid advocates to serve gay and lesbian students similar to paid staff the university had for Black, Chicano and women constituencies. In turn, Toy co-founded, with Cyndi Gair, what is now the Spectrum Center, the first campus office for LGBTQ+ affairs in the country.

The hiring of Toy and Gair as UM’s human sexuality advocates attracted national attention.Conservative writer Russell Kirk decried the new office as catering to the “farthest shores of lust.”

Far less about lust, the office pioneered educational outreach, counseling and programming for queer students that persists through to today.

Toy was a constant gadfly within the wider institution, helping to foster a 20-year effort to amend Regent Bylaw 14.06 to include sexual orientation as a category within the university’s non-discrimination protections.

At first quarter-time, the gay male and lesbian advocate positions were made half-time in 1977 and, with the hiring of Billie Edwards, full-time in 1987.

In a 1990 Ann Arbor Observer profile of Toy, his cherished friend Billi Gordon marveled that he survived so long on a part-time salary, living in an efficiency apartment and wearing second-hand clothes. “With the talents he has, if he were more selfish, he could be off in a large mansion someplace with boats and cars,” Gordon said. “Instead, he chose to serve others.”

While Toy helped make inroads over time, UM Law School alum Bill Dobbs suggests the creation of the office may have also muted oppositional energy that might have spurred sooner change. Dobbs met Toy in the mid-1970s when both were active in GLF and involved in Ann Arbors first gay community center. “He was a central figure in LGBT matters for decades,” Dobbs said of Toy. “At the same time Jim was very conscious that he was on the payroll of the University of Michigan and he played cards close to his chest.”

Toy held his job with the office until 1994, when UM administration reorganized what was then known as the Lesbian and Gay Programs under a single director with Dr. Ronni Sanlo hired for the position. Toy moved into a staff position with the university’s Affirmative Action Office.

He retired from UM in 2008.

His mantra was “Keep misbehaving.” From the 1970s onward Toy remained a dedicated instigator beyond UM as well. When Ann Arbor became the first city in the country to formally recognize Gay Pride Week in June 1972, Toy co-authored the proclamation.

A month later, with Human Rights Party council members Jerry DeGrieck and Nancy Wechsler, Toy helped draft Ann Arbor’s landmark ordinance that prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation. Though pioneering, the ordinance might have gone further in its protections. As the Ann Arbor Sun reported at the time, Democrats joined with Republicans to “deny transvestites and transexuals equal protections.”

Undeterred, Toy and others would continue the push to safeguard the rights of transgender citizens for the next 27 years. In 1999, he and Sandra Cole succeeded in securing a revised ordinance that included gender identity as a protected category.

His history of actions included a “zap” of the Rubaiyat nightclub to protest the bar’s ban on same-sex dancing and a picket of the American Psychiatric Association convention to demand it remove homosexuality from its list of mental disorders.

Strategic in his activism, Toy’s career as a gay organizer aligned with milestones of the Michigan LGBTQ+ past in the last half century, with Toy always involved, if not front and center then taking part in the rear guard.

Issues of faith held a special place for Toy. Along with serving on the commission for the Episcopal Diocese of Michigan, he worked with Bishop H. Coleman McGehee to achieve greater inclusion within the church. Decades later, Toy helped begin Oasis TBLG Outreach Ministries, a project of the Diocese initially housed at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Ann Arbor.

The Reverend Joe Summers, currently vicar of the Episcopal Church of Incarnation, served as staff person for Oasis from 2007 to 2018. He witnessed a shift in attitude toward Toy within the church, given that he’d “stirred up so much controversy early on.” By the 2010s, Toy was heralded for his commitment to inclusion and to racial justice.

“Jim was always looking at the intersections of different kinds of oppression,” Summers said, noting that it was Toy who insisted that transgender people be foregrounded in the TBLG in the ministry’s name.

As more mainstream churches have become more accepting, Toy’s work with Oasis has been carried on by Inclusive Justice, a statewide interdenominational coalition of faith communities. Toy served on its board until his death.

Toy participated in the founding convention in 1977 of the Michigan Organization for Human Rights, established in response to fears that Anita Bryant would bring her anti-gay “Save Our Children” crusade to Michigan. MOHR was precursor to the Triangle Foundation, which later merged with Michigan Equality to form Equality Michigan.

He served on the ACLU Committee on Lesbian Women and Gay Men, which in 1979 successfully prodded the administration of Republican Governor William Milliken to rescind Michigan’s liquor regulation that prohibited bars that were “rendezvous for homosexuals.”

When the AIDS pandemic emerged as a mortal threat to gay and bisexual men, Toy in 1986 helped launch the Huron Valley Chapter of Wellness Networks, later the HIV/AIDS Resource Center.

He was also a key co-founder in 1995 of the Washtenaw Rainbow Action Project. WRAP changed its name to the Jim Toy Community Center in his honor in 2010.

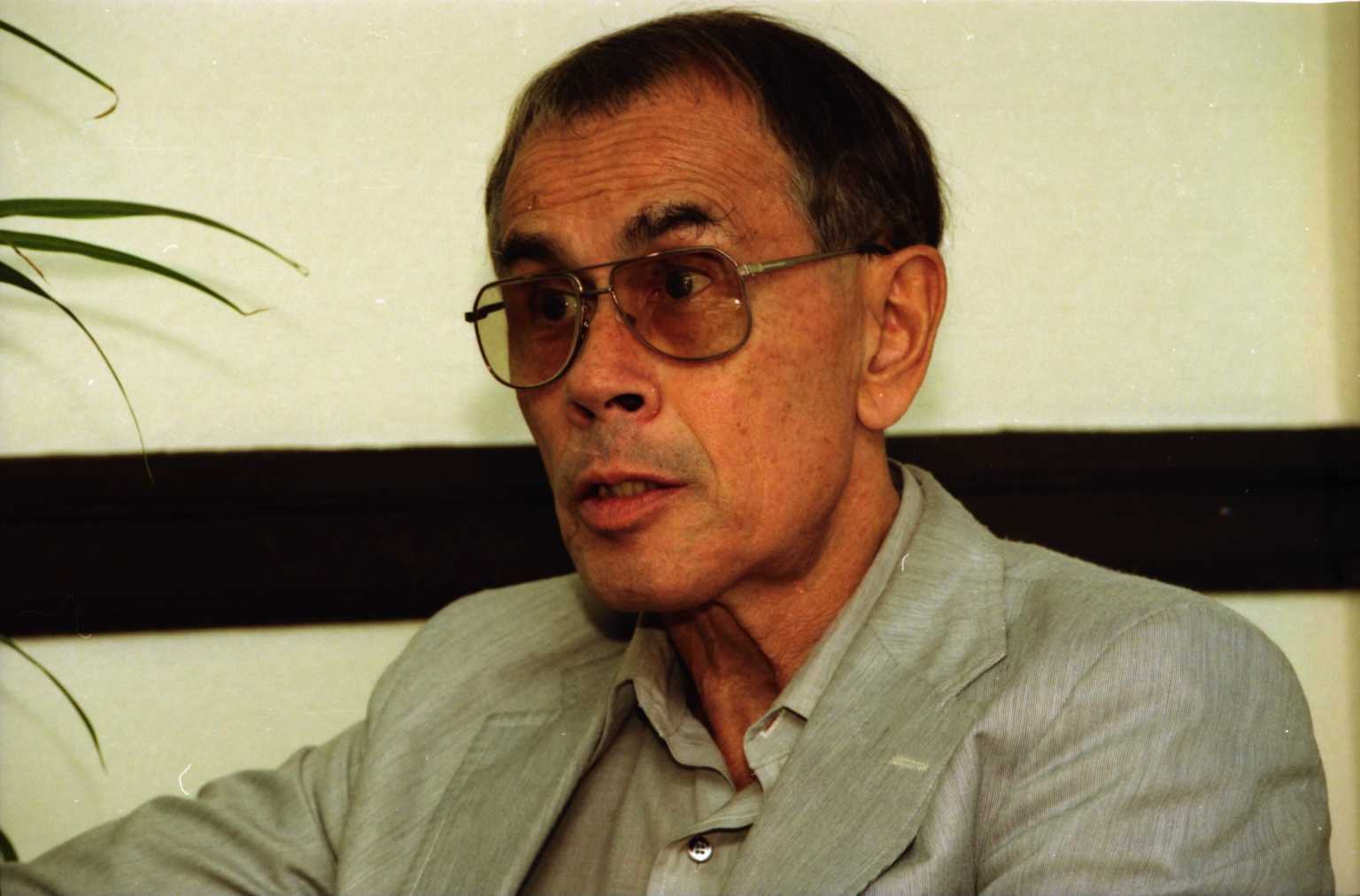

Wearing a yellow hardhat, a rainbow boa and tinted glasses, he was on hand in Braun Court holding court outside the center for the celebration following the 2015 Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges that legalized same-sex marriage nationwide.

Ann Arbor realtor and former Toy Center board president Sandi Smith was on hand for the occasion. “There was so much emotion that day,” Smith recalled to Pride Source.

“I always felt we were standing on his shoulders. None of this would have happened if he hadn’t taken those first brave steps.”

Smith’s wife Linda Lombardini, also a former Toy Center board president, concurred. “He always was a hero,” Lombardini said.

The memory that sticks in Smith’s mind of first meeting Toy as a first-year student at UM in 1981 when she made her way to the Lesbian-Gay Male Programs Office, was seeing an “impossible number of books and papers.”

Indeed, Toy was a packrat. Lombardini recalled the indelible image of Toy with his plastic bag with him wherever he went. The materials he collected were a legacy in themselves. In 1997, Toy placed his amassment of files with the Bentley Historical Library. Additional materials were transferred in 2020 when health necessitated him leaving his apartment to live at Hillside Terrace.

Contacted via email, Bentley Director Terrence McDonald shared these thoughts:

"Jim Toy was a model for us all both in how he lived and what he left. In life he was the gentlest but most unshakeable campaigner for what was right in so many areas; in death his legacy has been preserved in his magnificent collection at the Bentley Historical Library which is not only frequently used but has served as a magnet for other collections involving LGBTQ individuals. In this way, just as he was a pioneer in the LGBTQ cause in life, he has helped open a whole new understanding of that cause in the archives after his death."

In later life, Toy took to his role as gay elder with a sense of gusto and renewal. As ever, he was a gifted public speaker, precise with his language. In explaining to “Stateside” host April Baer on Michigan Radio in 2020 why he continued his activism into his ’90s, he said, “I’m stubborn. I’m committed to making as much trouble as I can to create and maintain justice.”

Over the past several years, accolades poured in. In 2016, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Association of Social Workers-Michigan. In 2017, Toy served as Grand Marshal of the Ann Arbor 4th of July Parade. In 2019 at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in Detroit, the Michigan Diocese named him a Canon Honorary, the highest position that the Episcopal Church bestows on a lay person. And in May 2021, the University of Michigan presented him with an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters.

As impressive as his public achievements, Toy’s greatest impact may have been on the personal level, in the lessons he left with those he affected on an individual basis.

In a comment on Toy’s Facebook wall early last year, friend Jay Aiken recounted the “royal waves” tutorials that Toy would give: “There’s the windshield wiper. The come hither (or beckon). And the classic screwing in the lightbulb.” Just one example of his regal poise and his gentle camp humor.

Toy was also a major fan of classic Hollywood cinema and was especially obsessed with screen icon Marlene Dietrich. In his younger years, usually in more private settings, he would don drag and perform as Marloona. One of his last and most public performances was for a Gender Bender Revue in the early 2000s held in the University Club in the Michigan Union.

Jim Toy is survived by his half-siblings Nancy Young and David Toy, along with two nieces, three grandnephews, and grandniece. Other survivors include longtime dear friends James Kangas, Scott Dennis, Jim Etzkorn, Jay Aiken and Tom Nickey, all who attended to his needs in his last year, as well as too many friends to count.

“When I was a kid, I was told, ‘We don’t talk about sex or politics or religion,’” Toy said addressing the Ann Arbor Pride celebration in 2018. “So, what are we going to talk about?

We’re going to talk about love and justice and higher ideals.”

Forty-six years earlier, Toy spoke to participants of Christopher Street Detroit ’72, Michigan’s first-ever Pride event. “I know that gay stands for love, and that gay stands for life,” he told the rally from the same podium in Kennedy Square where he’d come out publicly in 1970.

“Maybe that’s all I know, but that is all I need to know, and that is allyou need to know.So, I ask you to come out — come out for Love, come out for life.”

Plans for Jim Toy’s memorial celebration are in the works and will be announced at a later date.