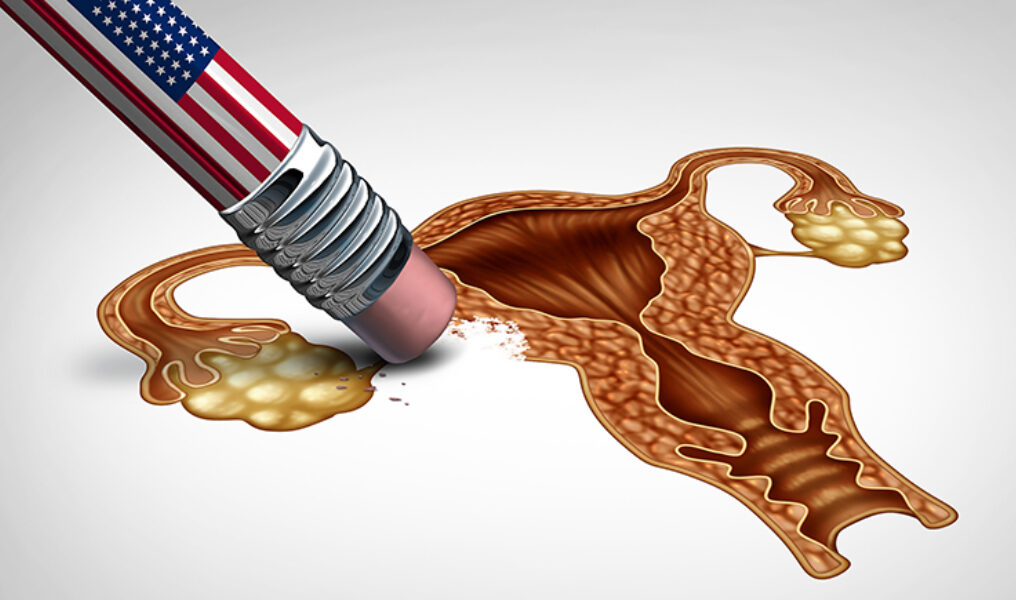

If Abortion Is Banned In Michigan, Is IVF Next?

Experts have more questions than answers about the future of assisted reproductive technologies

As of today, abortion is legal in Michigan. But after the Supreme Court so cruelly overturned Roe v. Wade, that right hangs in the balance.

Attorneys and lawmakers face mounting pressure to determine the extent of the fallout from the Court’s 6-3 decision on Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade. Among other potential issues, they question what an abortion ban means for the future of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Pride Source spoke with attorney Amanda Shelton, whose legal practice focuses on LGBTQ+ families.

“Right now, we're in a fortunate yet precarious situation,” said Shelton, who is also a married lesbian and a parent. “Because of the reversal of Roe, we have an automatic trigger back to our 1931 abortion law, which essentially prevents abortion without exception, but for the life of the mother. But it's very unclear what that really means.”

What “hovers” over us right now, says Shelton, is an injunction issued by Judge Elizabeth Gleicher in the Court of Claims, which essentially leaves Michigan at the status quo while awaiting a final decision from the Michigan Supreme Court that will determine whether the 1931 law is constitutional. Shelton sounds hopeful.

“We do have a more liberal majority than we have had in the last 40 years,” Shelton said, “so it feels fairly confident that we will get a good decision. But there's absolutely no guarantee of that. At the same time, we are working on the constitutional ballot initiative, and those signatures are due on July 11th.”

The Reproductive Freedom for All ballot initiative would add abortion rights to Michigan’s Constitution. Enough signatures have been collected, according to organizers; however, they will continue their efforts in order to ensure a strong defense against aggressive signature challenges.

As Michiganders navigate these uncharted waters, one of the many unknowns is the legal status of in vitro fertilization (IVF), a procedure which sometimes requires a selective reduction of embryos for viability or to protect the life of the pregnant person. It is, after all, a type of abortion. Destroying unneeded embryos could suddenly be problematic, too. And if that’s the case, existing frozen embryos might need to be stored indefinitely.

In IVF, sperm and eggs are combined in a lab to create embryos, one or more of which is placed in a person’s uterus. Patients often choose to store additional frozen embryos for future IVF cycles. Some experts believe that discarding extra or unneeded embryos is not affected by the abortion ban, but in some states, they question whether destroying embryos would be considered homicide under “personhood” laws. Michigan does not have such a law, though bills have been introduced in the past.

“I think it puts both women and doctors in a really precarious situation,” Shelton said, adding that doctors are forced to question whether they’re prepared to risk prosecution for performing a procedure. “The whole conversation between patients and doctors is incredibly hard. Weird, uncomfortable conversations. And it just shouldn't be that way.”

Shelton stressed the tremendous impact a ban on IVF would have on LGBTQ+ people, in particular, as the procedure is a very common method of forming families for many in the community. Twelve years ago, that’s the method Heidi Smith — who is a strong ally to the community — used when she wanted to have children but suffered from infertility.

“I have polycystic ovarian syndrome,” Smith explained, “which can cause the eggs not to release, basically, or grow enough. So, you have to go through treatment and lots of monitoring to monitor your follicles for egg growth and whatnot.” Smith said the process involved multiple medications including injectables, “tons” of doctor’s appointments and cost a significant amount of money.

After three rounds of treatment, Smith had a positive pregnancy test, and her doctor thought she might be carrying multiples. Indeed she was — five babies in all. At that point, the doctors looked concerned, Smith said.

“They said, ‘This is not good. This is, like, extremely risky,’” Smith said. “’We do not recommend that you go through with this pregnancy.’ They just said this right away. They said, ‘let's go talk about it.’ So we went back to the doctor's office and she immediately started going over all kinds of statistics about my health or you know, the chance of death in this process.”

They discussed the statistics of all five babies surviving and the chances of severe disabilities. Smith was sent to a doctor who specializes in high-risk pregnancies, then another. They discussed options. She was referred to a doctor who had developed a new procedure intended to increase the likelihood of the babies’ survival, as well as Smith’s life.

“Emotionally, could we handle carrying them all and losing them or [face] the risk to my own life?” Smith asked. “So ultimately, it just seemed like with all of our doctors, all the different specialists we talked to, and we did different testings, all kinds of stuff to see what would be the best decision for us, and we decided to go with the reduction to twins”

Smith underwent the procedure. She carried the twins until 17 weeks, when one of their water broke. In the end, she lost both of the remaining twins. For those who look down on her decision to reduce, Smith has a message.

“When you see people say that people don't value life, like, I totally value life,” said Smith, whose daughter was born at 26 weeks. “I've seen it before my eyes. I've seen the different stages and the fragility. And I've watched my daughter fight for her life outside my body. But I just don't think it's fair, the situation that we're in, because nobody would choose to go through painful things. Does that make sense?”

The day the abortion ruling was no longer a promise but a done deal, Rep. Samantha Steckloff and her staff began work on legislation that would ensure IVF treatment stays legal.

“We're in this interesting limbo,” said Steckloff, echoing Shelton. “If not for this injunction, we would have no idea. This law, this 1931 law, was written in the 1800s, well before any medical advances. And then you add in Roe, which was 1973. And then the first IVF was in the '80s. So nothing's been looked at since this technology became prevalent. And the only reason I have a feeling this is an issue and why I'm aware of it is because I've been working on IVF for some time.”

Steckloff was diagnosed with cancer in 2015. Facing the loss of her fertility as a result of chemotherapy, she went through treatment and had the eggs frozen. Had they been frozen embryos, it would have complicated matters because Steckloff is no longer with her partner from that time.

“That was the first time I started understanding that the legal ramifications in general of an embryo are very weird,” Steckloff said. “You would have to get permission. I would've had to get permission from my ex-boyfriend to use [the embryos]. And if he said no, and all my chances were in embryos, then I would've completely lost any chance for having a child. So moving forward, I have been trying to figure out personally what my journey is.”

IVF is increasingly common, emphasized Steckloff, who said she has many millennial-age friends who have sought treatment. In fact, 55,000 births occur annually via assisted reproductive technologies (ART), of which IVF is the most common. According to CDC data, in 2019, ART was responsible for 2.1 percent of all births in the United States. One third of Americans say either they or someone they know has undergone infertility treatment.

Steckloff also mentioned surrogacy, not only common for cancer survivors but also for LGBTQ+ people trying to conceive. However, Michigan is one of two states where the practice is illegal. Steckloff has been pushing a surrogacy bill for two years.

“I remember being in a conversation in a representative's office, a Republican representative, and their chief of staff was there talking about how they went through IVF,” Steckloff said. “And we started talking about why Right to Life and the Catholic Conference is so against surrogacy. And it predominantly has to do with the embryos. So that's why I know this embryo situation is already an issue. So that's how I came about looking into codifying a law.”

Shelton advises clients — or anyone — considering IVF to have very clear conversations with their doctors about what their intentions and expectations are in forming their family. Patients must be assured doctors will adhere to their wishes. It’s critical to discuss contingency plans in the event that things go awry.

Personally, Shelton said she was experiencing anger, fear and grief.

“Although we saw the train coming, it's still shocking that it hit us,” said Shelton, referring to the Dobbs decision. “I am mourning for my clients who are now racing to me. I have gotten 10 calls in the last two business days about trying to rush through second parent adoptions because people are terrified that if same sex marriage is overturned, they're gonna lose rights to their kids. People are panicking. They're panicking. It's heart-breaking.”