Viewpoint

On Feb. 26 Trayvon Martin, a seventeen year old African American youth, went to the store to get a pack of skittles and an Arizona tea. He wasn't a bad kid. He'd never been in trouble. He was unarmed. He just went out for some snacks and never made it back home.

Trayvon was shot by a member of a neighborhood watch armed with a semiautomatic handgun. George Zimmerman described Martin as suspicious and "looking like he is up to no good."

Zimmerman, who is reportedly Hispanic and grew up in a multi-racial family, claimed self-defense, was not charged and was released by police.

In the aftermath of the shooting, there has been a groundswell of protest across the internet and country demanding an investigation of the shooting, an arrest of Zimmerman and drawing attention to the sad reality that, even now in 2012, there remains a bull's eye on the backs of young African American and Latino youth.

At the height of the protests, discussions and calls for justice, "Fox & Friends" commentator Geraldo Rivera urged parents of Black and Latino youngsters to "not let their children go out wearing hoodies" implying that the wearing of "hoodies" was somehow a contributing factor to the bounty on African American and Latino youth.

HOLD THE PRESSES!!!!!!!

As an African American I get it. I had had the talk with my son about dressing, walking, driving and living "while Black." I personally have been followed around stores by suspicious clerks or security for no apparent reason other than my skin color and had to "whiten up" my vocabulary to get or keep jobs.

It's fear – fear of the unknown, fear of the "other." It's stupid, unjustified but it is real – to some a black person in a hoodie at night is still code for "looking like he is up to no good" and subject to suspicion, surveillance and, in Trayvon's case, shooting. We may have overcome but we still have one hell of a way yet to go.

But as I listened to Rivera's remarks saying basically if only Black and Latino youth didn't wear hoodies they would somehow be safer, I once again found myself at that oft crossed intersection of human rights and LGBT equality.

I cannot tell you how many times while lobbying for anti-bullying legislation not just before federal and state legislators but at school boards, churches and various community groups, the argument against comprehensive, enumerated anti-bullying legislation was wrapped around the "if only" argument. – If only they didn't dress that way; if only they didn't want to openly express their sexuality or gender expression – If only they weren't Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual or Transgender.

What exactly is bullying? Miriam-Webster defines bullying as the "use of superior strength or influence to intimidate (someone), typically to force him/her to do what one wants."

But we don't need Webster to tell us about bullying. In lay terms it's more often "If only you behave, follow our rules, be what we want" – we'll leave you alone; let you keep your job and dream of equal rights.

Race, class, hate and fear all crashing at the intersection of civil rights, LGBT equality and our humanity.

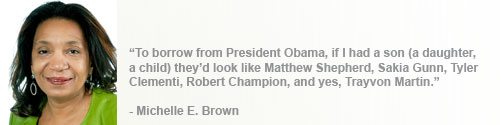

To borrow from President Obama, if I had a son (a daughter, a child) they'd look like Matthew Shepherd, Sakia Gunn, Tyler Clementi, Robert Champion, and yes, Trayvon Martin.

We must think about our own kids and ask what can we be that our children might see today? What kind of world are we leaving for them tomorrow?

"If Only" – two words at the heart of our fight to protect our families, our communities, and our youth. We don't need to change. We need to be the change.

If only we stand up against bullying, and stand for justice, we can be the change we want to see.