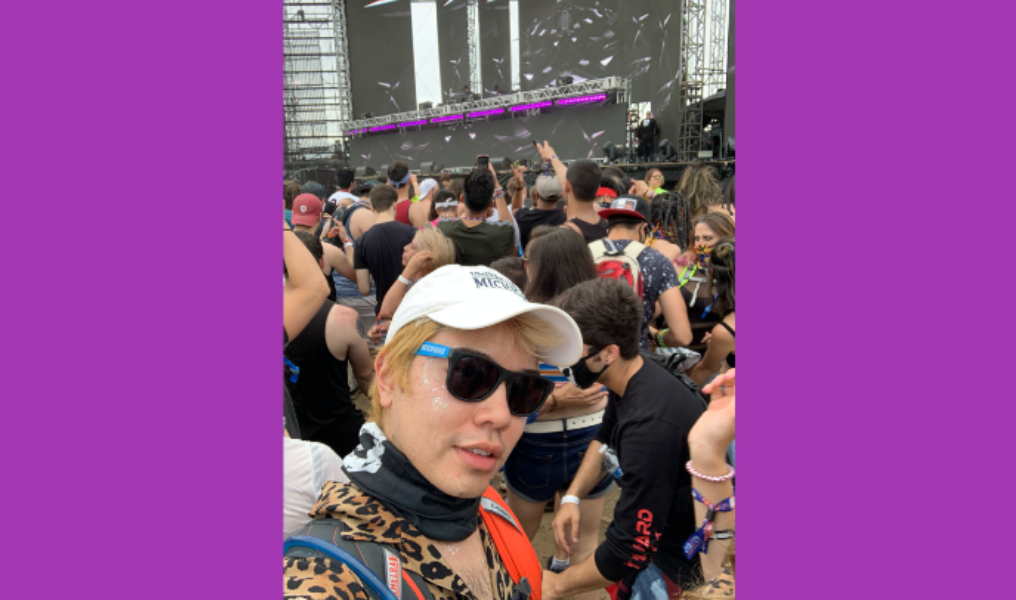

Colin Thanh is used to raving under extreme conditions. Pouring rain or searing hot, it doesn't matter: Thanh is there among the drugs and sweat.

After many hours of soaked dancing in the mud at this year's Lollapalooza Festival, Thanh and his friends went back to their hotel room where, he says, "we put the music on, and we had our own little mini rave within our friend group."

Thanh is part of a group driving the rave renaissance, according to Plan A Magazine. But this new wave is different — it's no longer about the middle-class white ravers of the '90s. Modern rave events in recent years have been steadily full of Asian faces. In fact, Subtle Asian Ravers (SAR), a Facebook group for Asian ravers, had 97,000 members at press time. Though Asians have always partaken in the rave scene, the increase in Asian participation in contemporary electronic dance music (EDM) festivals and events is something of a phenomenon. One factor that seems to be influencing this trend is the fact that the roots of the EDM scene have their origins in queer subcultures shaped by marginalization and resistance — something queer Asians understand fundamentally.

Sitting at the confluence of raving queer resistance and the modern Asian rave scene, these partygoers find community, joy and acceptance in the scene, which, for the queer Asian demographic, is a communal experience that harks back to collectivist cultures that highly value group gatherings. At events, Asian ravers can be spotted in groups of "rave families," with the term "rave mom" or "rave dad" designating the raver who introduced the others to the scene and to the family. There is also often one raver there to support the rest of the group, offering small fans to keep them cool and water for hydration.

For Thanh, a gay Vietnamese-American raver from Ann Arbor, the sense of community within the rave scene helped him be comfortable with his sexuality and come out. He went to his first rave at 18, "shocked by the way people dressed," he recalls.

"I didn't come out when I was 18," he says. "I was still exploring all the options, and raves were definitely a big change. I worried about how people would perceive me. Now I'm totally open, and I don't care what people think about me when I'm at a rave."

Thanh's main obstacle to being fully out was body image. As a teenager, he struggled with how he looked. But he found the rave community to be a safe and supportive space to be Asian and queer. "I saw how everybody was so comfortable with their bodies and with their outfits at all these raves and concerts. It made me realize that no one's here to judge on how you look," he says. "That had a big impact on how I perceived myself, how I learned to love who I am and not to take any crap from anybody else."

Even Thanh's style changed. It was bolder, and the makeup he wore and the glitter on his skin reflected his true self. Then he started sharing beauty tips with fellow ravers. "Now I'm totally OK with going up to someone and saying, 'I really love your makeup; how'd you do that?' It was definitely challenging at first; it's not easy to go up to some random person and just start talking to them," he says. "But now, after having many years of going out and raving, it's second nature to me."

Kate Moo.

A bisexual Chinese-Singaporean raver from Rochester, Kate Moo could only accept herself once she immersed herself in the rave scene. "I've known I was attracted to girls for a really, really long time. But I was always a bit in denial about it. I thought this was just a phase," she explains.

Moo's mother is a devout Christian who refused to acknowledge the existence of queer attraction. She felt invalidated by her mother and suppressed her attraction to women for many years. "I thought I was not supposed to feel like that. My mother and father told me that it wasn't real, that you're not supposed to have these feelings and thoughts," she explains.

But then Moo started going to raves as a teenager. She says she was around 15 years old when she found herself surrounded by queer students and students of color at International Academy, a public high school in Bloomfield Hills. "When I met all these new people, I started going to concert raves and hanging out with them," she says. "I was exposed to way more diverse perspectives. It was a very racially diverse school." Under the bright strobe lights and away from the watchful gaze of her parents, Moo felt free. It made her realize she wasn't alone with her experiences.

Similarly to Thanh, Moo felt accepted and embraced just by watching queer ravers in rainbow gear with Pride flags. It was then that she gradually came out. She started telling her friends about her queerness and attending Pride events around a year after she started raving. Now at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, she feels comfortable casually mentioning her sexual orientation in conversation.

Kareem Khubchandani, an author and researcher who specializes in queer Asian nightlife, isn't surprised that so many queer Asians have been able to find a home within the rave community. "For a lot of people, nightlife is their initiation into queer community. It's a space for people who are exploring their identity and looking for an alternative to the kind of heteronormative life they live," he says. "But for a lot of queer Asians, showing up in a gay neighborhood or a gay bar means often finding themselves in a white space. So there's been a lot of organizing to create alternative spaces for queer Asian folks."

According to Khubchandani, the queer Asian organizers who put on these events tend to plan with more intent around the specific crowd they're hosting. This intentionality is reflected

in who is on the guest list, the identities of the night's performers, and the kinds of music being played. Organizers might decide to make an event exclusive to queer Asians and put Bollywood or K-pop on the set list. It allows queer Asians to have a space that is just for them in a world that is dominated by whiteness and heteronormativity.

For Moo, her rave family in high school had a distinct routine every time they went to a rave. Since they were underage and could not go to clubs in Detroit, they would all gather at a friend's place and pregame before driving out to the event. On their way back, they would all go to an IHOP before heading back to Rochester.

Though COVID-19, meant Moo and other queer Asian ravers had to gather together virtually during the pandemic, she's already looking forward to clubbing at Electricity in Pontiac and attending Electric Forest at Sherwood Forest in Rothbury, Michigan. "It sounds like the coolest venue because they hang lights, decorations and artwork from trees," she says. "They're lit up 24/7 during all the weekends of the festival."

Thanh remembers when he went to Movement in Detroit before the pandemic with his rave family and they hung out and bonded on the riverfront. Together with his friends, they watched other queer Asian ravers dance. That alone, he says, was a powerful thing.