Meet the Gay Latinx Actor Playing Alexander Hamilton in Detroit

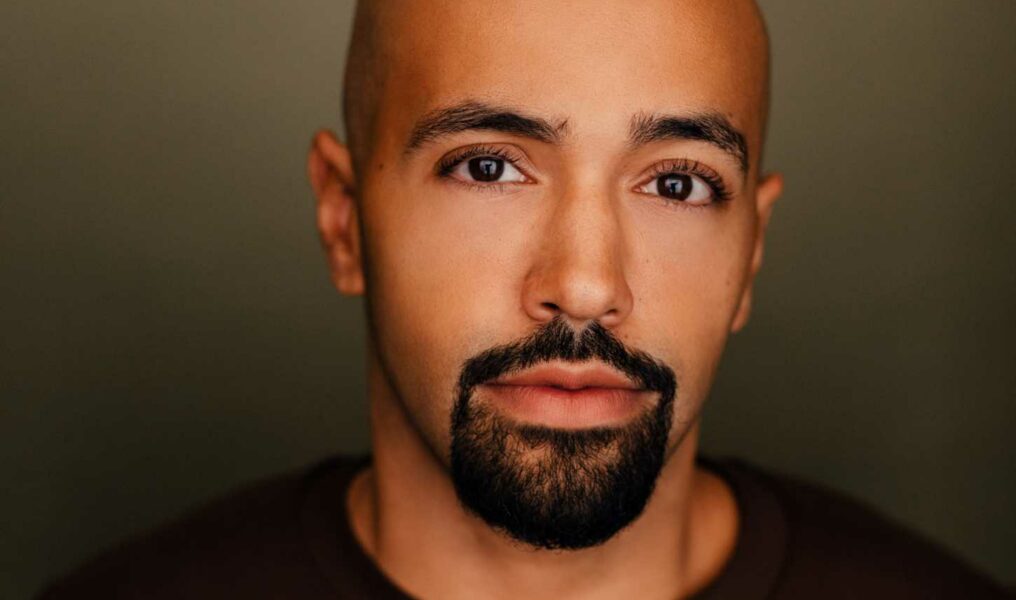

Pierre Jean Gonzalez on his journey to the spotlight and the life-altering impact of representation

In the musical bearing his name, Alexander Hamilton is a man all too aware of both his impermanence and his influence. There could never be enough time to do all that he dreams of doing, and he’s not about to “throw away his shot.” Pierre Jean Gonzalez, who plays Hamilton in the national North American touring cast, seems to be living a moment not dissimilar to the role he dreamed of playing.

“It’s a big spotlight,” Gonzalez tells Pride Source on a recent Zoom call. “And that’s why I’m not taking it for granted.”

Gonzalez knows full well that time in the spotlight can be fleeting. And while the spotlight is shining on him, he wants to do what he can to light up issues he feels have been obscured in darkness for too long. It’s why his t-shirt prominently displays the logo for his production company, DominiRican Productions, a passion project created with his work and life partner Cedric Leiba, Jr. And it’s why he tends to lead with his identity as a Latinx gay man as much as possible.

All that is not to say Gonzalez is unwilling to talk about his experience with the mind-blowingly popular musical (the Broadway production alone has grossed more than $1 billion), which will play the Fisher Theatre in Detroit Nov. 15-Dec. 4. “Let’s talk about ‘Hamilton,’” he says, flashing a hopelessly charming, 100-watt grin. “But at the same time, I’m also going to throw in my mission for this show. What this show represents is aligned to everything that I represent as an artist.”

“Everybody can have their opinions about ‘Hamilton.’ There shouldn’t just be one ‘Hamilton,’” he continues. “But this show gives opportunity for other playwrights of color, other queer, nonbinary, trans people, to see themselves in these roles and be like, ‘You know what? I can write something.’”

Playing Hamilton has been an exhilarating experience, he says, despite an ill-timed pandemic pause. Gonzalez was set to debut on March 27, 2020, but after a few delays and increasing chatter throughout his hometown, New York City, it became clear that “Hamilton” was going dark along with the rest of the arts world. It would be another 18 months before Gonzalez finally took his first official curtain call as Alexander Hamilton.

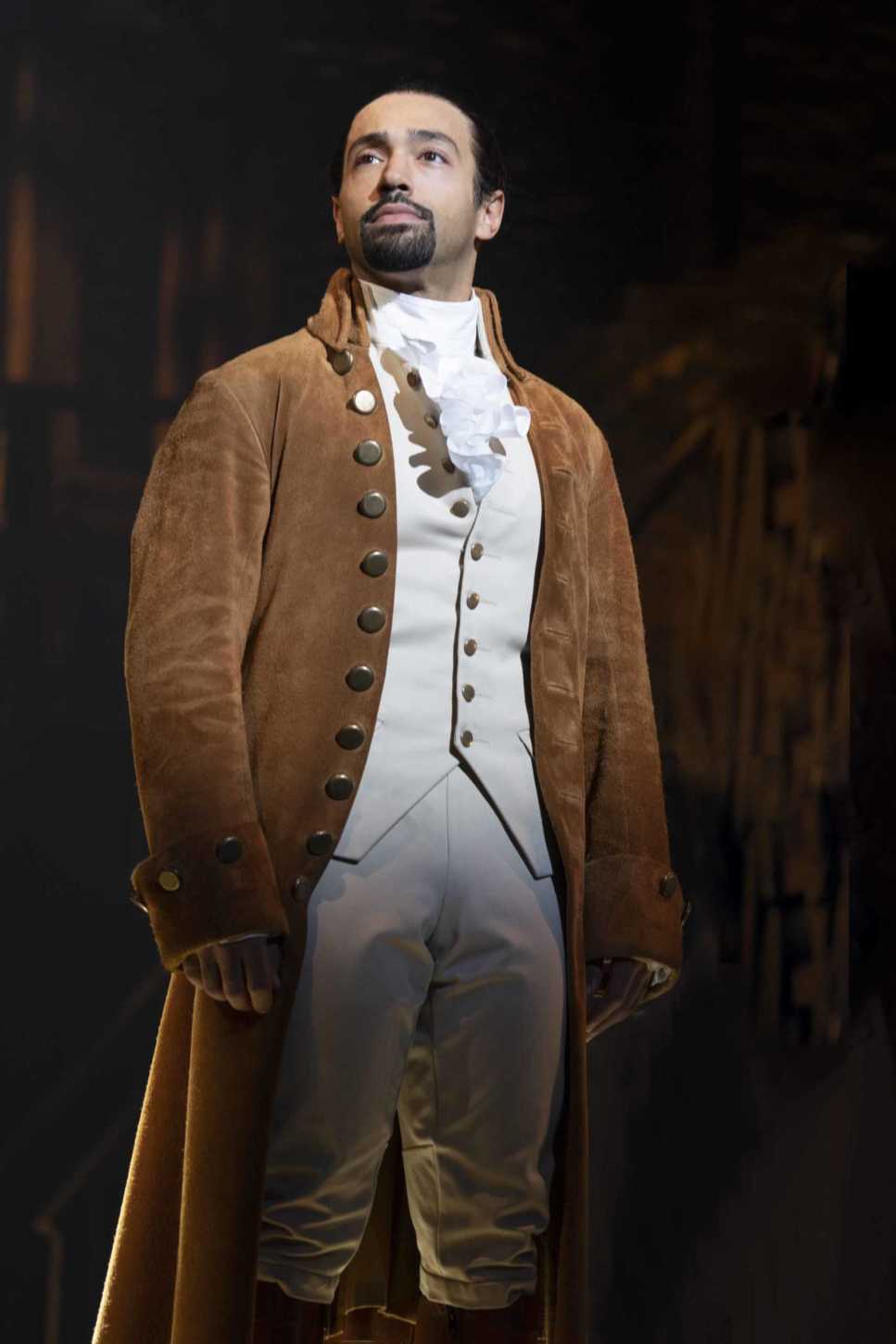

While many of us spent a significant portion of those 18 months hunkered down, counting the days until “normal” might return, Gonzalez doesn’t seem to run that way. Hamilton himself, composer Lin-Manuel Miranda tells us through song, was a prolific, frenetic author who wrote like he was “running out of time,” and when Gonzalez was given the gift of time he didn’t expect to have, he wasn’t about to waste it, either.

While the world lurched uncertainly, Gonzalez and Leiba considered where to devote their energies. What was most important? How could they make the most impact, together, even within the confines of pandemic limitations? Those conversations eventually birthed DominiRican Productions, a co-venture focused on increasing representation in media for overlooked stories — Afro-Latinx stories, in particular.

“I think it was a need at first to distract ourselves because of the craziness that was happening,” Gonzalez says. Not only was the couple coming to terms with the realities of what the pandemic shutdowns would mean for their livelihoods and day-to-day lives, but as 2020 unfolded, another reality was setting in: the growing protest movement around the George Floyd murder by police in Minneapolis.

“The country was coming to a reckoning of how we were treating black bodies,” he says. “And Cedric and I, we wanted to make a difference, or just have an effect on our community. A lot of Afro-Latinos are not represented in media, and also in our community, we still have issues with people who are darker, you know? [Darker] isn’t always seen as beautiful. That needs to change.”

COVID-19 logistics presented both challenges and opportunities for DominiRican’s early productions. “We could get people in the same space that wouldn’t be normally,” he recalls. Leiba and Gonzalez invited friends and families to an online screening of the first project, an experimental short, “release,” which would go on to win several filmmaking awards, including Best Experimental Film in the 13th annual Fargo-Moorhead LGBT Film Festival. The film, shot in the Bronx, where Gonzalez grew up, is centered on Leiba’s poem, also called “release,” which explores his inner artistic struggle in the face of outside pressures.

After the Zoom screening, friends started asking the couple to help film their own projects. Soon, Steven Luna joined the DominiRican team and the project took on a life of its own. “At the end of the day, I wanted to be able to create a space where my artist friends felt seen and were able to create work they can have ownership of,” he says. “Because in this industry, being queer, being Latinx, being Latina, it’s such a small pool of work that really talks to our experience. We’re all fighting for this one role, and I was just like, ‘I’m over it. I’m over it.’ We’re so much more vast than that.”

Before “Hamilton,” Gonzalez racked up credits on TV dramas like “NCIS” and “Quantico,” often portraying gritty characters in trouble. The more direct line to “Hamilton” may be between his earliest work as a classically trained actor at Rutgers University, which included training through Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London. These days, he’s moved away from taking on roles that perpetuate stereotypes or don’t accurately reflect his ethnicity.

“We’re not just thugs,” he says, tearing up. “We’re beautiful. We’re kind. We’re smart. We are people in power. We are people — you know what I mean? We’re everywhere. I just really wanted to make sure that we showed not just the trauma of what we are, but the beauty that comes out of that trauma.”

Gonzalez acknowledges that right now, in the 2022 U.S. political climate, for him, merely existing is a form of activism. “I am a gay Latinx man playing the lead of this show. And people are watching me, and they’re accepting me in this role. I never dared dreamed this reality,” he says. “I crippled my own dreams. I would, like, stop myself and be like, ‘That’s not going to happen for you, Pierre. You’re gay, so nobody is going to believe that you’re playing this role or that role.’ And that was the reality for me, even five or six years ago.”

Gonzalez can’t pinpoint an exact moment when his mindset shifted, but there came a point when he’d simply had enough. “I made a conscious choice with my agents, and when Cedric and I had conversations about what makes us happy and what roles we want to choose, I stopped.” He told his agents that he was done playing roles that weren’t based on who he is — a Dominican Puerto Rican man from New York.

“I was going in for these Mexican American roles, Salvadorian, Brazilian, and finally I was like ‘I’m not doing this anymore.’ There are way too many Mexican American actors, way too many Cuban actors waiting for the opportunity. You want to see me? I’m a Dominican Puerto Rican man. If you want to shift the character, if that can easily be shifted, absolutely. But otherwise, go find actual Mexican Americans.”

“The minute I started leading with that and stating that and being authentically myself, that’s when things started to kind of shift. I started to demand the respect, and you get to see me for who I am,” he says. “And the minute I started doing that, that’s when everything started to align. I stopped trying to hide who I was, my queerness, my New York-ness, all of it.”

Gonzalez notes that there’s still plenty of work to do on the representation front, but projects like the rom-com “Bros” give him hope. “It was an epic thing,” he says, “and not just because Cedric was in it.” (Leiba plays Harness Guy — if you know, you know). The fact that “Bros” was backed by a major motion picture studio is huge, he says. “That doesn’t happen for us. And it doesn’t matter that it’s following white men. We’re working toward something. And if we don’t show up for the work, if we don’t buy the tickets, if we don’t click, if we don’t do the views, then they’re not going to back our stories.”

It’s almost impossible to imagine that only a handful of years ago, Gonzalez wasn’t fully standing in his truth. Like many queer people, his coming out story was not the magical tale of acceptance and love. As a teenager attending a Catholic high school in the Bronx, queerness was not exactly a badge of honor. At one point, he says, he internalized the idea that there wasn’t going to be a time when he could ever come out. “I had accepted that I was just going to live a lie,” he remembers. “I stopped myself from experiencing so much, and I wasn’t out until I was outed — I was forced out of the closet —[and] it was a very traumatic, really scary, horrible time for me.”

“But I’m so grateful that I got through it,” he adds.

Even after the trauma of being outed as a teenager in a toxic, non-inclusive environment, Gonzalez says it took several more years before he entirely accepted himself. Now, when he spots a fellow underrepresented actor in the wild trying to make it on the merits of who they are, Gonzalez reaches out a hand.

“This is not a competition for our community anymore. We can’t compete with each other,” he says. “We don’t even know what we’re capable of yet, because we were never given the opportunity.”

Today, Gonzalez draws a great deal of inspiration from Generation Z’s matter-of-fact approach to identity and sexuality. Faith in the upcoming generation helps to keep him focused on the positive at a tumultuous time in history for the LGBTQ+ community. “I just want to be part of the solution. How can we fix this? How can we resolve this? How do we create a conversation? How can we keep it positive? Am I pissed off all the time about what I’m seeing? I’m heated. Livid. But I can’t live my life like that.”

And so, whether he’s promoting DominiRican Productions or doing press for “Hamilton,” Gonzalez puts his queerness and his ethnicity front and center. “I think that’s our job as the queer community at this stage, at this place. That’s just our burden that we have to carry.”

Gonzalez says he and Leiba often talk about how queer media is evolving. In many ways, he says, it’s about sharing knowledge outside the community. “It’s part of our job to educate and to push our narrative and to teach people our experience,” he says “And it’s the kids’ job to live through it and enjoy it in a different way. We can’t put our burdens onto them.”

“It’s not perfect,” he adds. “It’s never going to be perfect. And I don’t think we’re going to see a world where our queerness is going to be represented perfectly. That’s for the future. Our job now is to really educate and to push our stories out there. That’s our job right now.”

“Hamilton” runs Nov. 15-Dec. 4 at the Fisher Theatre in Detroit. Tickets available through ticketmaster.com.