What Every LGBTQ+ Person Needs to Know About the Threat to Abortion Access in Michigan

The intersection of reproductive justice and LGBTQ+ rights is too great to ignore

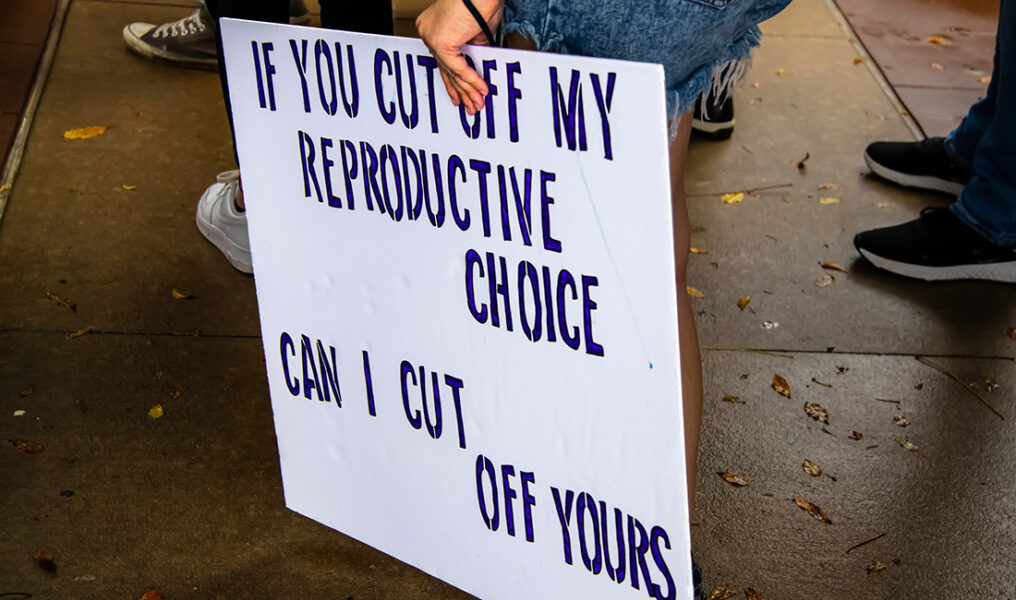

For anyone who values reproductive freedom, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

In what’s widely considered the most consequential Supreme Court case regarding abortion in decades, a majority of justices appear poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that established a Constitutional right to abortion. A decision on the case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, is expected to be handed down this summer.

“If Roe gets gutted completely, then it will become an issue where it is decided by the state,” explained Lara Chelian, director of advocacy and development at Northland Family Planning Centers, whose clinics provide abortion care at three locations in metro Detroit. “And that is probably the most dire issue because then it becomes based on your ZIP code where you live [as to] your access to abortion.”

The state of Michigan would revert to a 1931 law that has until now been superseded by the Roe decision. The law states that, with the exception of saving the life of the mother, providers who carry out abortions would be guilty of manslaughter.

In response, a ballot initiative is currently in the works that would amend the state Constitution to protect the right to abortion. “Our goal in this ballot initiative is to protect abortion access so that people don't have to cross state lines to access reproductive health care when they choose to seek it,” Chelian said.

A WDIV/Detroit News poll conducted in January 2022 found 67.3 percent of Michigan voters want Roe. v. Wade left in place, including 54.7 percent who strongly feel this way.

Not surprisingly, some of the most passionate voices in the debate, like Chelian’s, are from those who work in the abortion care field. Pride Source spoke with Fitz, a patient care advocate at a clinic in Michigan that provides abortion care. Fitz asked that we only use his first name.

“It's upsetting,” Fitz said, in regard to the Dobbs case. “That's really my feeling about it. We talked about it a lot at work. We are working on the ballot initiative and petition drive which we're going to be getting out soon, which I'm very excited about.”

A gay, transgender man, Fitz began at his place of work by volunteering to help shield patients from protesters outside the clinic, commonly known as clinic escorting. When a patient advocate position became available, Fitz opted for a career change after experiencing burnout at his previous work in nonprofits and in the social work field.

“Immediately, I started loving it,” Fitz said. “Like, as soon as I got hired. I was extremely happy. I love my job.”

The fight to keep abortion safe and accessible is personal for Fitz. But that’s not to say he had an abortion. When Fitz was 19, he gave birth to a child that he placed for adoption. He stressed he was fully aware of the options and made the decision freely. He stays in contact with the family.

“They've been incredibly accepting throughout my transition,” Fitz said. “But the big thing about that choice, and when it came in my life, was that it did offer me a choice. Previous to that, I'd been very depressed; things in my life had not been going great.

“I was kind of questioning myself a lot,” he continued. “And while I didn't transition or really even know I was trans until a couple of years later, that pregnancy and that choice — and knowing that I had a choice — was a big, huge life-changing moment for me.”

Fitz felt confident that all options were available to him. Yet access includes more than whether or not an option is legal. When it comes to abortion access, LGBTQ+ people often face barriers to a greater degree than the general population. That can be as basic as the health care setting.

“When I have to go to the gynecologist, I really don't feel great about it,” Fitz said. And even if the practice has a reputation for being LGBTQ-friendly, “I go in and I'm the only man in the waiting room. Instantly, everybody either is suspicious of me or knows what I am. So even just getting over that hurdle to make it to the appointment is a big challenge.”

Chelian explained they go to great lengths to provide a comfortable and supportive environment where she works. It starts with simple things like using the term “pregnant people” instead of “pregnant women.”

“[In] our clinics, we work to ensure that LGBTQ-identified people feel safe, comfortable, and are welcomed as who they are,” Chelian said. “So anyone [who] has a uterus and needs access to abortion care, they can come and not fear any judgment or fear any stereotypes. And I think it's something that doesn't get talked about enough.”

Setting foot in a clinic is one challenge. The cost of an abortion is another.

“I would say price is probably the biggest barrier for a lot of people,” said Fitz, “and, you know, a lot of the LGBTQ population that would need to access those services are predominantly poor. And if they do have insurance, it’s state insurance which, by state law, [is] not permitted to cover anything regarding abortion services.”

Without insurance or the assistance of abortion funds, an in-clinic medication abortion (abortion pills) or a first trimester surgical abortion both cost $500 on average. Later in a pregnancy, a surgical abortion can cost several thousand dollars. Then consider that poverty affects 22 percent of LGBTQ+ people in the U.S., compared with 16 percent of the general population. The highest rates of poverty are experienced among transgender people and cisgender bisexual women.

“Intersectionality is always kind of a bitch,” Fitz said, speaking of the obstacles LGBTQ+ people might face when seeking abortion care.

As they wait for the Supreme Court decision, both Fitz and Chelian are confident that in the fight for bodily autonomy, the reproductive justice community and the LGBTQ+ community are natural allies. In Fitz’s experience, the two communities go hand in hand or are so closely aligned as to be one and the same.

“Almost every LGBTQ person that I know is a staunch, reproductive rights advocate, and vice versa,” Fitz said. “I think that discovering yourself and making those hard introspective choices…about yourself is really kind of the core of what it's about."

Chelian said she can see the two groups banding together even more, because the intersection of all of their issues is too great to ignore. "We're all fighting the same thing," Chelian said. "We all want to live our own lives, from of judgment, free of impositions [on access to the] healthcare we see fit for our lives."