Where the Past Meets the Present: Capturing Pride 40 Years Ago

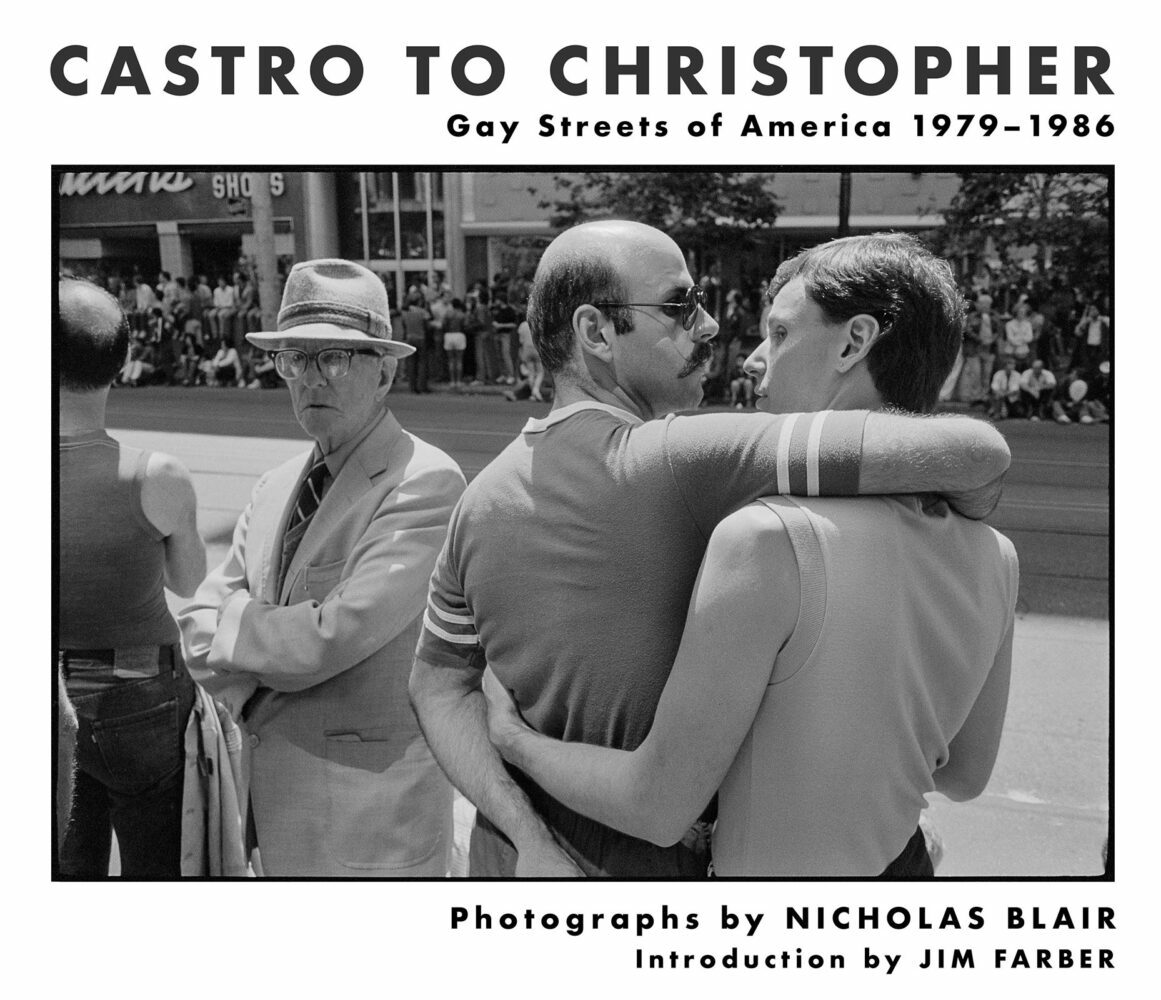

A new photography book is an echo from another time

Are we capturing history every day without even knowing it? Forty years ago, photographer Nicholas Blair wasn’t intentionally immortalizing a specific era of what we now call the LGBTQ+ community — he just felt compelled to take photos wherever he could find queer life. That included places where the queer experience was vibrant and loud, like San Francisco’s Castro district, New York’s West Village and the Christopher Street Pier, and Provincetown, Massachusetts. Many of Blair’s photos were taken during Pride festivals, where drag queens freely expressed themselves, a mother held up a sign that read “We love our lesbian daughter,” and queer couples shared tender and passionate affection. Through photos alone, the book emphasizes the point that, yes, history really does repeat itself (and I’m not only talking about all the queer boys in this book who can’t seem to find shorts that are short enough).

Shot during “the vanished world of gay life before AIDS,” many of those black-and-white images are featured in a new photography book called “Castro to Christopher: Gay Street of America 1979–1986.” Blair’s photos capture a queer revolution, both the quiet, intimately loving moments and loud, indignant determination to be seen and treated equally in a country that still, in many places currently, like Florida and Tennessee, does the very opposite.

In a recent interview with Blair, he spoke about what it was like to capture this era of LGBTQ+ people and places — and what has (and hasn’t) changed since then.

A ‘backyard’ cultural revolution

I dropped out of high school [in 1973] and hitchhiked through South America for about a year. When I came back to New York City, I had a lot of time to think about what I wanted to do. I thought I might try to go into film, but in New York a good friend gave me a Leica camera, a little camera to use. I went out to San Francisco, hitchhiked out there to be with my brother, and we ended up starting an arts commune called the Modern Lovers Commune, which was a loosely knit group of people, many of them who liked to travel as well, but who were all into art, and then eventually started Ancient Currents Gallery in that same space.

One of the trips that I took was in late 1977. I went away for a year to India on this super low-budget walkabout with my camera and my friend, just photographing through India, and actually Pakistan and Europe. When we came back to San Francisco, it was two weeks before the tragic assassinations of Harvey Milk and George Moscone. I was a hippie-type person; I'd been harassed at different times. But San Francisco seemed like a very safe space. I mean, we had gay people living in our group. It was very fluid and seemed very open and safe, and this was a big wake-up call.

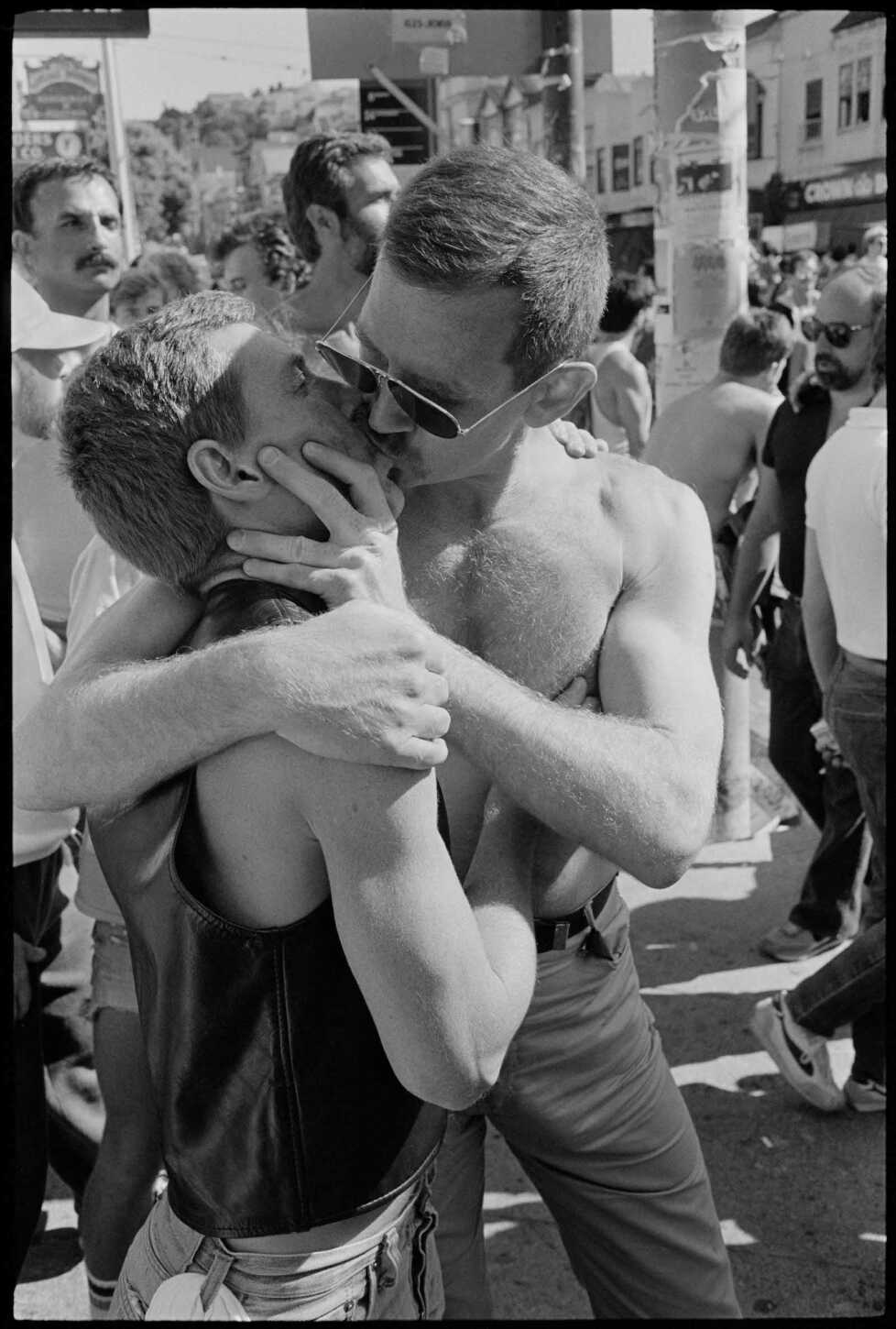

Castro Street Fair, San Francisco , 1983.

Perhaps beforehand I was a little naïve, but this idea that all of a sudden people were getting murdered, it took me a little while to get myself together after coming back, and then I went to some events, some political events in the gay community. I photographed pretty much all kinds of things going on in San Francisco, and I was really drawn to what was going on in a lot of ways. I had traveled before that and never had I seen anything like this.

It was a cultural revolution happening essentially in my backyard, and I was really just drawn to it organically. I mean, I would like to say, "Oh, I had this overarching political agenda to try to document the situation then." But it was just more like, "Wow, this is really interesting." There was a lot going on. You just didn't know what you might run into.

The beginnings of ‘Castro to Christopher Street’

My brother had been living in Brazil and Peru for almost two years. He was very interested in Tobias Schneebaum, an anthropologist who was gay. My brother interviewed him, wrote a big article on him, and sold it to The Advocate. They published it, and my brother saw that I had some of these pictures from Castro Street. He said, "Well, maybe you should send some to The Advocate." We were basically what you would call starving artists, trying to make a living any which way — a lot of house painting at that time. But so I sent some to The Advocate. They said, "Great, we love it." They published a full-page spread, and that of course got me even more interested, so I went down to the Bay Area Reporter office. They call it BAR now, which was a local San Francisco paper.

So I had just a stack of maybe 30 five-by-sevens. I walked into the office. I can't even remember who I talked to, but there was an editor there. He just looked at me and said, "Great. We'll run a weekly photograph. What do you want to call it?" I was just like, "Why don't we call it Castro to Christopher Street?"

It just sort of evolved. I covered Pride San Francisco twice, and New York once, and I think I covered Halloween a few times in San Francisco. It was such a fun event, just so different then, both Pride and Halloween. I mean, Pride, you could just walk out in the street.

I liked to photograph the bystanders, not really so much just documenting the floats and what's going on in the parade. But with The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence [the same charitable drag group that dress up as nuns that the Dodgers recently honored, then dishonored, then re-honored after a Catholic uproar], for example, you feel like, "Oh, they're coming down the street. I'll just walk out in the middle of the street and hang out and photograph them.”

Landing on a cover photo

Well, I did have some help from some friends looking through images, and tried different ones. I guess what I liked about that is the strong formal nature and the tension of the way the image is laid out and captured, the way the two guys are looking at each other in this. I wouldn't say adoring, but admiring. They're so close; they're almost pulling their heads back just a little so that they can see each other better.

And the love. I'm very attracted to just outward displays of affection, in the gay community or really with anybody. It's just something that's an eye-catcher. But then this older guy… I like this ambiguity in photographs. I like to say there are truths in a lie. Because they're a truth, because optically it's showing you what's going on. But you really don't know. You could say those two guys are gay, but maybe they're just friends. You really can't say for sure, and you don't know what's outside their frame, what's inside their frame. My thinking is that this might just be an older gay guy who's come out.

Looking back to make the book

In trying to complete the book, there was a question of how to do it. It took a long time to kind of organize the material. "Am I going to do it ontologically? Am I going to do it just all Pride, or how is it going to be arranged?" So of course I wanted the strongest images, but it also felt like I have to flush out certain topics specifically, which are kind of pivotal on the gay calendar or in the gay community. I didn't label the chapters, but some are what I would call sort of everyday life, and then there's Pride San Francisco, Pride New York. There's, of course, the AIDS crisis, Halloween and the Pier.

Castro Street, San Francisco, 1984. Photo: Nicholas Blair

Capturing history without knowing it

I think in retrospect, this is what I noticed: At the time it seemed just like, "Oh, this is a normal course of events." But now, 40 years later, it really seems like this is the inception of something that I believe is going to go on for hundreds of years. Of course it goes back to probably Stonewall, 10 years before these images were taken.

I wish I had started earlier, but I could not see the importance from a historical perspective at that time. I mean, I wish I was that astute to be able to say, "Wow, this is the beginning of a cultural revolution. I've just got to get out there and photograph and cover this," because there's so many things I wish I would have covered that I didn't cover. I think I was [making] $15 per photograph from BAR. So I guess it's really become more of a document than I imagined at the time. But in retrospect, I think it is a very historic time.

Putting the book in public schools

I was thinking of just writing the biggest high school in Texas a letter. Let's just start with 50 of them. I mean, this is still a little bit of a pipe dream, but just saying, "I would be happy to donate a copy of my book to your high school." See what's the response. My friend was like, "Oh my god, what if you're going to have to donate hundreds?" I was like, "Well, maybe that would be a great thing, you know?" And these are places where they're actually getting rid of books and they don't want to have these books. And so for somebody to be able to run a library, who tends to be queer and just say, "Hey, here's a photo book." I'm going to try it, just because it's so easy. I picked Texas. It could be any number of states.

What has changed in San Francisco since 1979–1986

I go out there occasionally. I'll be out there this summer. When you're down in that area, you can just feel that it’s sort of a gay area, but it's not like it was. Even the Pier, it’s common to see a photo of somebody just lying around, sunning themselves on a towel, and even the garbage… the wood is rotting, and now that's all gone. And I see people just walking around all over town now. It's not that uncommon in New York City to see a same-sex couple holding hands. I still look at them and I say, "More power to you." But you know, my mother is a Holocaust survivor and I'd still be afraid to go around with a Magen David hanging around my neck, I'll be honest with you. I admire people that can do that and feel free.