A Kind of Defiance: In Lansing, an Overlooked – and Leading – History of Queer Activism

It’s only natural for a state capital to become a center for political activism. But in the case of Lansing, both local and state-level queer activism have taken on a remarkable variety of forms. From early flickers of visibility there in the 1950s and ‘60s to feminist-lesbian coalitional work rippling out from the 1970s across decades, the city’s history makes clear that the gains won last March, with LGBTQ+ protections being enshrined within the Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act, didn’t spring from nowhere.

As activists, historians, archivists and residents of the city have emphasized, these victories were the result of hard work — resulting in bits of progress that could, with some effort, be undone. Even so, the city (and state) have come a long way.

Of the city’s early history, Tim Retzloff, a Lansing resident, Pride Source contributor and queer historian at Michigan State University (MSU), observes that the climate for queer people (at least those we’d regard that way now) in the 1930s and '40s could be oppressive in Lansing (and next door in the smaller city of East Lansing, home to the university). Even within the insulated bubble of a campus environment, being out for most anyone proved an impossibility. While the city’s university presence attracted a mix of people — some queer and others open-minded — the visibility, prestige and the school’s state also made it a target for a sort of “clamping down," according to Retzloff.

“There were these kind of agents in society and of the state at the university — and certainly in the city of East Lansing and Lansing — that tried to tamp down any kind of nonconformity in terms of sexuality and gender,” Retzloff observes, citing the university’s concerns about reputational harm. But, at the same time, he suggests, “there were definitely people who were finding each other.”

As a result of these kinds of tensions, pre-1950s evidence of queer community in Lansing remains “fragmentary,” but still present, Retzloff says, describing the city’s queer people then as living in a kind of “defiance against social norms.”

Within both our Zoom conversation and his sweeping overview of the city’s LGBTQ+ history for the queer-owned publication Lansing City Pulse, he notes the quiet presence of Lucile Portwood and Evelyn Sanders, a lesbian couple who moved to the area in the early 1940s for school and became known, beyond their careers, for their successful entrants in dog shows. Around the same time, Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler, another couple, joined MSU’s art faculty and commissioned a Frank Lloyd Wright House in nearby Okemos. Retzloff notes that Albert Hakala, too — a gay man Retzloff interviewed

for City Pulse last summer — taught at Lansing’s Eastern High School alongside his partner and fellow educator, Bob Walker, who eventually became the school’s vice principal. The two had managed to meet despite a difficult climate during their studies at Northern Michigan University in the 1940s before pursuing master’s degrees at what is now MSU.

While these cases may have been exceptions in terms of their legibility today, attempts to build such connections seemed to become, as in many American cities, easier over time. The late 1950s and then 1960s gave rise to increasing openness within the growing local bar scene, with visible community emerging after Stonewall by the 1970s from all corners of the city — including among the manufacturing workers, many of them queer and lesbian women according to Retzloff, of its bustling automotive sector.

Even as the queer community blossomed into a newfound sense of visibility, though — with the founding of the Gay Liberation Movement (GLM) on MSU’s campus in 1970 and a march on the Capitol in December 1971, certain divisions remained in the community. With gay men and lesbian women each having long lived not just quietly but in a sense of isolation from one another, the two coalitions didn’t always feel a sense of common ground.

With the exception of moments of crisis (such as the AIDS epidemic in the years to come) or political solidarity (as in the march above), gay men and lesbian women often felt driven to find and grow their own separate spaces, with sexism and gendered tensions often creating a kind of wedge. It was within this context, then, that Lansing became not only a space for both queer men and women but an unlikely, enduring hub for lesbians nationally — and a driver for the broader national community.

A separatist moment

Within a climate rich in tensions — between heightened visibility and raised political consciousness, gendered divisions and queer solidarity — and a desire for stability as well as for change, Lansing established its own distinct gay and lesbian spaces. As Retzloff recounts, a gay community center opened its doors in 1972, with a constituency overlapping heavily with the GLM; meanwhile, the Helen Diner Memorial Women’s Center opened in East Lansing around the same time before moving to Lansing in 1975 after a dispute with their landlady. One of five lesbian centers nationally by 1978, it’s this second space that became a key community fixture not only for locals but for lesbians well beyond Lansing’s border.

For Paige Hodder, a lesbian-identifying automotive reporter at Crain’s Detroit Business, this history and practice remains an animating subject — so much so that she made it, along with a second, unaffiliated lesbian center quartered in Ann Arbor, the subject of her undergraduate thesis. While the weekly newsletter published from the Lansing center became one of her research’s primary concerns, a second, monthly publication gave Lansing’s center its broadest geographical reach.

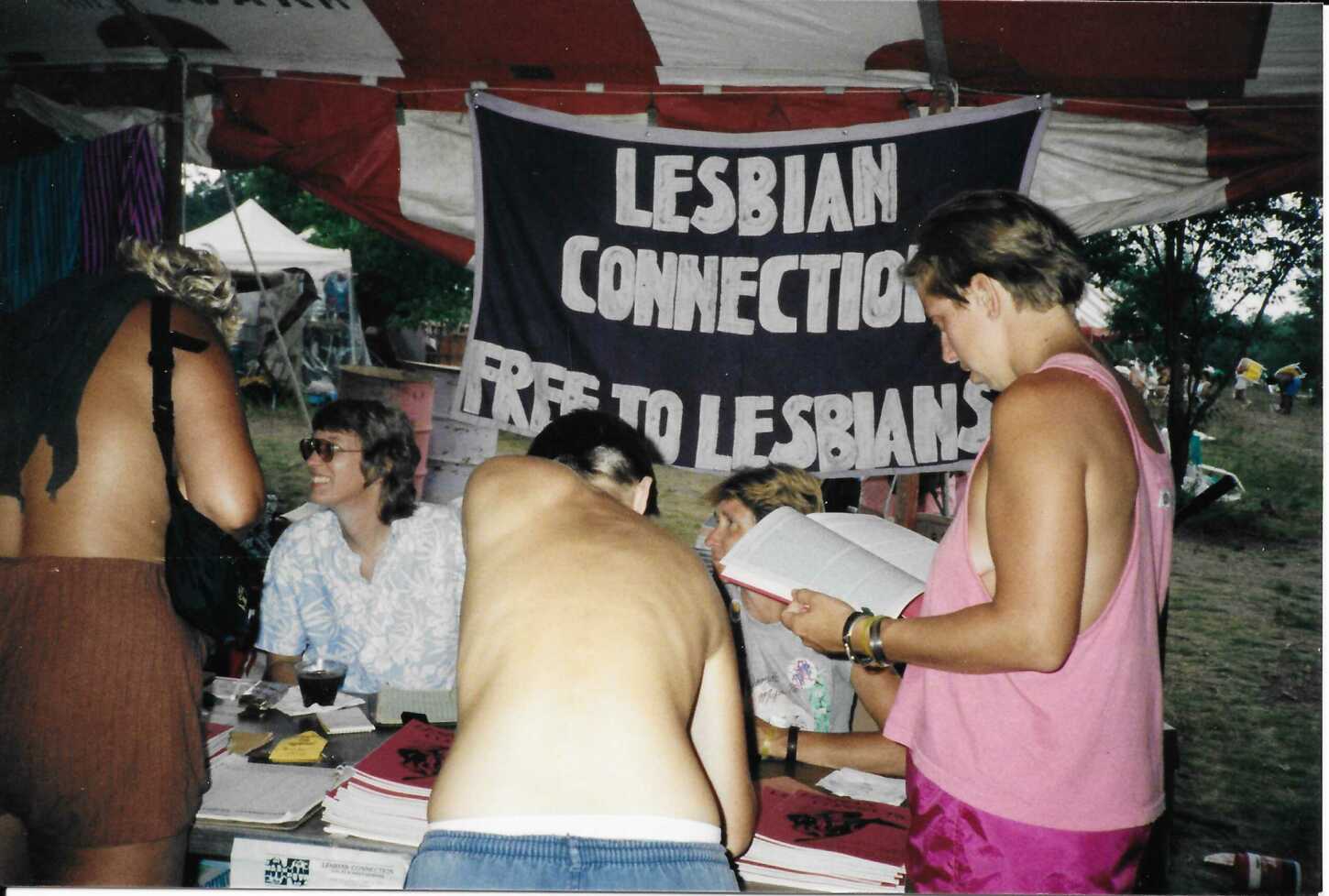

Hodder describes this second publication, The Lesbian Connection, as a “massive magazine, sort of filled out by contributors across the country. They would collate it all and self-print it, literally in the basement of their community center, and then send it out across the country. By the end of the 1970s, it was probably one of the biggest and most-read national, lesbian-specific publications.”

But despite this reach, the emphasis at the Center itself, suggests Hodder, was less on outward-facing political change than a feminist ethic of care, support and mutuality enacted locally — even as visibility remained a key driver.

“My thesis really focused on ‘internal activism,’ if that makes sense: how these communities were working to support each other,” says Hodder. “They were certainly focused on legislative action and stuff like that… But at the same time, they were focused on helping each other fill in the little things. They would bring in a hairdresser, sometimes, who would volunteer to do more gender neutral or butch haircuts that would have been difficult for women to get elsewhere.”

In addition to the Center’s publishing work, other activities, Hodder remembers, included carpools, potlucks, dance parties and coffee houses. The aim, she says, was to “fill the gaps” left by the familial and other supportive networks so many of the women had lost — providing even legal and financial resources in the spaces and moments they were most needed.

One central fixture among Lansing women’s spaces was the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, which ran from 1976-2015 in nearby Hart, Michigan, and was founded by three women. According to Eli Landaverde, the librarian for MSU’s LGBTQ+ collection,

the festival became a haven for women well outside Lansing, and even Michigan.

“The incentive was to do a kind of Woodstock thing, just for women; that was the background of it. And it really caught on,” Landaverde observes. “The festival was not meant to be only for lesbians — that was not the main idea.”

A similar separatist ethic seemed to drive the concurrent, continuing success of Goldenrod Music, founded in 1974 by Terry Grant. Like the festival, Goldenrod’s mission was informed, according to musicologist Lauron Kehrer, by the lesbian and radical feminist thinker Marilyn Frye, who advocated for the exclusion of men and the problems they brought with them from as many spaces as seemed “feasible” within women’s lives.

But the festival became, along with the Lesbian Connection, Goldenrod and the adjacency of the state Capitol, an animating force despite this, drawing women to relocate to Lansing for its sense of community. Lesbians would come, notes Landaverde, from “all over” to attend the festival, often straining to make arrangements and depending on the hospitality and support of like-minded local hosts.

Landaverde says there’s a kind of “chicken-and-egg” question regarding the origins of Lansing’s sturdy lesbian institutions of the time. With Lansing’s status as a capital city, the pull of MSU and a range of lesbian organizations all strengthening the community, it’s hard to single one out as an initial driving force or cause.

Lesbians lead the charge

For Cheryl VanDeKerkhove, a lesbian activist and longtime resident who moved up to Lansing after visiting in 1982, the robust sense of community was palpable years after these institutions’ foundings — outstripping what was available for queer women even in her then home of Metro Detroit.

“This is more than just bars – it’s literally a community up here,” recalls VanDeKerkhove of her experience of Lansing at the time. “If you were into sports, they had pretty much all the sports. If you were into politics, definitely a lot of political stuff going on. If you were into, you know, sewing, there's a sewing circle… Whatever you wanted to do with other lesbians, you had a chance to do it here.”

For VanDeKerkhove, community participation eventually evolved into work on the Lesbian Connection newsletter alongside DJing dances and other work at the Center more broadly. The sense, says VanDeKerkhove, was of more robust engagement and mutuality than the hook-up mentality and romantic orientation that undergirded so much of queer bar life.

“In the Detroit area, it felt like you could go to a bar, and you could see other lesbians. And they'll charge you five or ten bucks for the privilege to get in — but that was it,” she remembers. “Whereas in Lansing, you could go out, meet people — and then you could take that to another level and actually socialize outside of a bar, and do things together that are fun; be there for each other and get involved in actions and do nonprofit work. There were things to do with your time and energy in community, as opposed to going to a bar to drink and find a partner.”

While creating distinct spaces did much to promote the flourishing of Lansing’s lesbian community, the separatist ethos, even while carving out a space for women, was one whose enactment often failed to make everyone feel welcome. Speaking to these stakes as they stood in the late ’70s, Hodder explains that the approach modeled by Frye and enacted in so many ways locally encountered opposition both often and early from varying fronts.

“They didn't want just equality; they wanted to center their lives entirely around women — which was entirely disruptive to the gender binary and the family system. At the same time, these groups also faced a lot of criticism from feminists of color, from gender-nonconforming queer people, from trans people, because a lot of their ambitions [aims] were primarily championed by the work they did — centered around mostly white, middle-class, lesbian goals and experiences.”

Evolving beyond LGB

For Rachel Crandall-Crocker, the co-founder of Transgender Michigan along with her wife Susan Crocker, these concerns persisted in both social and activist spaces over her decades spent in Lansing beginning in 1978. After starting to come out in 1993, she became closely involved with Lansing Association for Human Rights (LAHR) around 1998, eventually going on to found Transgender Day of Visibility in 2009, an experience informed by the frictions involved in her ongoing experience of activist work.

“Very few people had ever met a transgender person. And there I was at their table all of a sudden — and people were not crazy about it,” she recalls, describing participation in Lansing’s queer community throughout the 1990s as “an uphill climb.”

“I had to do an awful lot of education,” Crocker remarks, speaking to her experience on boards for LGBTQ+ organizations. “That’s what Transgender Michigan was all about; it was really about education and support.”

With time and effort (and no shortage of conflicts), the broader community became more understanding of Crocker’s concerns, though an essentialist strain of thought in Lansing’s feminist community and history made it harder to roll advocacy efforts into broader queer organizations. The Womyn’s Music Festival, for instance, declined to feature transgender-centric panels, and local Pride organizers often didn’t see a space for trans people in their work.

“There was a lot of discussion,” Crocker recalls. “Why doesn’t an LGB organization focus on their rights and come back for us? However, I did not like that idea.”

While advocating for that stance, she worked in the meantime to create solidaristic spaces of her own, some beginning modestly, including a gender-nonconformist group that met at El Azteco, an East Lansing Mexican restaurant, and a Transgender Picnic event which followed her through her eventual relocation back to Metro Detroit.

Increasingly, due to these and other persistent efforts, cross-coalitional solidarity became a kind of prevailing model both at both a local and a broader level: one which VanDeKerkhove, who’d found fulfillment in the more separatist models of queer community mentioned previously, worked to embody in her own activism and ongoing work. By co-founding the Real World Emporium in Lansing’s Old Town (both then and now a particularly visible queer neighborhood within Lansing) in 1994, she worked to address longstanding rifts within the local queer community.

Even in LAHR, she recalls, an organization founded by two women, none were present in leadership roles by the late 1980s; in terms of racial diversity, too, she remembers only “a little drop of color in there, on occasion,” demonstrating an imbalance she sought to amend. “Our intent with the bookstore all along was to make it LGBT, because what we saw with the lesbian bookstores that had come prior is they couldn’t sustain themselves. And so we wanted to have something that the community could access — and hopefully that would make a large enough customer base to keep a store like that going in Michigan.”

As not just a business but a responsive form of both political and communitarian work, the store — until facing the twin blows of a divorce with her partner and co-founder, along with construction obscuring foot traffic at a key moments for retail in the late 1990s — proved successful, making it a cross-coalitional anchor for the queer community until its closure in 1998. By this time, LAHR and other local institutions increasingly reflected similar, cross-coalitional models.

Modern LGBTQ+ community-building

Today, this cross-coalitional work seems to color local understanding not only of activist work but of the city’s geography as a whole.

Benny Vasquez, one of several directors at Lansing Pride and a nearly lifelong area resident, remembered that after a brief movey to Houston for work, she felt acutely conscious of her identity — and need for safety — there, in a way she never had at home in Lansing.

“That said more to me about Lansing than it did about Texas because that made it very, very obvious to me how caring Lansing was. And how little I had to worry about,” Vasquez said.

“Realistically, I don't think there are queer neighborhoods. I think there are straight neighborhoods. I think there are neighborhoods [where] the rich folk have gathered, and they're all at least presenting as straight,” she remarked. “And so those are the anomaly; anywhere else I go, I see Pride flags… it’s less about pockets of non-straight people than pockets of straight people.”

One memorable exception to this, at least by the mid-1990s, was an east side neighborhood known as Dyke Heights, a space VanDeKerkhove for years called home, and which, as a home to a dense population of lesbian women, evoked some flavor of the area’s longtime separatist models.

“I lived on Holmes Street with Cindy, my wife at the time. And one morning at 6:00 a.m. we heard a woman screaming outside. So we ran out with a baseball bat, out of our front door, to go see what was going on and tried to help, only to see, probably, a dozen other lesbians from all the different houses on the street, also running out in their bathrobes with their baseball bats to try to find out why there was a woman screaming. It was just us, it was all lesbians, but we ran out to see what we could do to help. And you know, if that's not an example of an experience of community, I don't know what is.”

The scream, said VanDeKerkhove, was caused by an aspiring purse thief – and the culprit fled when her posse of defenders made their presence known. Their effort at achieving solidarity had worked. Today, MSU’s Gender and Sexuality Center offers tours of the area and other queer local landmarks — though it’s less clear if they know or discuss this particular event.

Looking ahead

While the coalitions — and battles — have shifted over time, constant work and a readiness to fight remain the rule in Lansing’s queer activism, which stands as. It is a continuing source of life for the community. Even in the wake of recent gains, complacency seems not to be an option.

“It’s not necessarily relief or anything like that,” said Vasquez of the atmosphere locally after the ELCRA amendment. “But this place — our corner of the world — feels a little bit safer. Because we know that level of backing is there.”

Given queer representation’s growth at both local and state levels — with lesbian attorney general Dana Nessel, an openly gay city clerk in Chris Swope and an ally in the governor’s mansion — that sense of governmental backing has seemed, with work, to grow. As of this past election, too, much of Lansing can call claim Emily Dievendorf, who is looking out for the local LGBTQ+ community as a queer, nonbinary person, as there new state representative. Dievendorf even has a downtown bookstore of their own.

“It’s representation at its basic level, right?” said Vasquez. “With politicians, the fact that they can be where they are, and open – and not have to hide or downplay the part that they play in the LGBTQIA community – that means that we don’t have to, either.”