How This Feminist Music Icon Gave Queer People Permission to Have Intense Emotional Feelings

ani difranco has inspired queer people of all generations by doing her own thing for over 30 years

Moments before a Zoom interview with revolutionary folk-rock singer-songwriter ani difranco, my computer dies. It just absolutely flatlines. Desperation chokes my heart, and I scramble for her manager’s phone number. Fortunately, professionalism trumps fangirl anxiety, and I’m assured ani will be in touch.

Shortly thereafter, my cell lights up with this incoming message: RIGHTEOUS BABE, BUFFALO, NY.

“Hi! This is ani calling!” the voice says. Aloud, I respond: “Oh Lord.” It’s go time.

Right away, I take care of some general journalist housecleaning. All good reporters start out with the simplest of questions: What’s your name and how do you spell it?

With a quick modification, and my tongue somewhat planted in my cheek, I ask: “Do you spell that with a lowercase or capital A?”

I know I wasn’t the first writer to ask this question. Things have evolved, though, since ani difranco first established herself as an influential artist in the early 1990s.

“I always write my name lowercase, but it’s not a rule or something,” she tells me. “I write everything lowercase. You can do as you wish, but the rest of the world tends to capitalize my name like theirs. It doesn’t matter to me, I guess.”

Taking notes during the interview, I type “ani difranco” into my laptop. It’s how she writes her name. I think of k.d. lang, who often pointed to her love of poet ee cummings in her use of nonstandard punctuation. I didn’t get a chance to ask ani why she doesn’t push back on people who insist on capitalizing her name, but can’t help thinking how societal arrogance and, perhaps, the patriarchy keeps the public from always seeing ani as she sees herself. But she’s polite. I can tell she picks her battles.

And, because I’ve been following her since 1991, I also know she’s never going to hold back.

Expect nothing less later this month when ani headlines the 46th annual Ann Arbor Folk Fest, slated for 6:30 p.m. Jan. 28 at Hill Auditorium. (The Folk Fest weekend will officially kick off Jan. 27 with the Friday Night Folk Banjofest, set for 8 p.m. at The Ark in Ann Arbor.) The festival returns this year after a two-year pandemic-related hiatus. And ani’s return is a homecoming of sorts, as she has performed at the festival several times since her first appearance in the mid-1990s.

Noting the break, we both agree the last two years have allowed for a social shift.

“I feel more and more people are waking up,” she says, referencing the uprising in 2020. “There is a critical mass of people who are now acknowledging the inherent inequality and entrenched oppression in our system, in our government, in our culture, in our country … so this is thrilling.”

Technological advances, including smartphones and the ability to livestream, have transformed how society accesses and absorbs information.

“I predate the smartphone, so I knew the world before,” she says, describing times when people would slip through the cracks and never make it to “your own private Idaho. But now you meet them. They are in your pocket.”

The first time I heard of ani difranco must’ve been back in 1991 when a Righteous Babe cassette made its way to Mount Pleasant, Michigan. I was a junior at Central Michigan University, and even though I wrote about my fluid orientation in a column for the student newspaper, back then there weren’t a lot of out gay role models.

During this time in college, I frequently met with a small group of queer gals. Together, we shared the latest music by powerful female musicians, turned the volume to 10 and daydreamed about which of those artists could possibly be gay. During one of these sessions, someone pulled out ani’s newly released “Not So Soft” album. “The Whole Night” was the first queer song I heard that hit me in the heart.

We can touch

Touch our girl cheeks

And we can hold hands

Like paper dolls

We can try

Try each other onIn the privacy

Within new york city's walls

Early in her career, ani’s lyrics about attractions without borders quickly gained a strong lesbian and bisexual fanbase. Her song “In or Out” — with lyrics “Some days the line I walk turns out to be straight/Other days the line tends to deviate” — became a bisexual anthem after its release on her 1992 album “Imperfectly.”

However, the interface of queerness and dominant culture and society has at times proven a challenge.

“For me, I’ve been consistently me. And other people can appreciate it or not,” ani says, noting a momentarily backlash when she began dating a man (she’s currently married to

producer Mike Napolitano, with whom she has two children). From the first page of her 2020 memoir “No Walls and the Recurring Dream”: “I remember once walking out in New York City to get some kind of queer award and getting booed … for not being queer enough … before I even reached the podium.”

This reaction proved confounding for ani, who had consistently presented her sexual orientation as fluid.

“In terms of resenting me for being me, not the me [that fans] would have prescribed me to be …. what can I even do about that?” she says, adding she realized a long time ago that she couldn’t please everyone all of the time. “Especially when there are so many in my type of work to make happy. Which of us can be what every other individual in the world expects or wants of us?”

ani recognizes the contradiction, and lives unapologetically.

“I try not to let all those pressures and judgements stop me, certainly, and I try not to let it get me down for very long,” she says. “It’s part of the gig. It’s a great, great gig.”

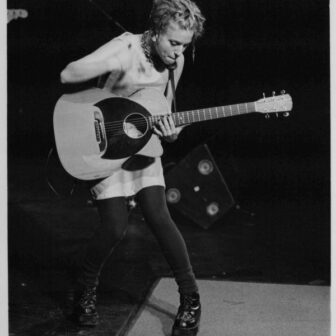

ani’s music label Righteous Babe Records describes her latest album “Revolutionary Love,” released in 2021, as proof of her “rare ability to give voice to our deepest frustrations and tensions, on both a personal and political level.” The 11-song collection gathers influences from myriad music genres, including blues (“Shrinking Violet”), R&B (“Bad Dream”) and jazz (“Do or Die”). And her trademark in-your-face fingerwork is front and center in the intro of folk-fusion song “Simultaneously,” which alludes to the shift of the world we live in.

I live in two world different worldsSimultaneouslyThe one where we are fracturedAnd the one where we are freeFreedom requires safetyYeah, freedom requires trustYeah, freedom requires balanceIn the equation of us

Identity has served a constant thread through ani’s music, from gender to sexuality to politics.

“I look at my kids. I have a teenager, and identity is like a weight that they have to carry. It’s a job they have to do daily. It’s a performance that they have to put on, and get right,” she says. “And especially in this new online existence, this social media living-through-screens that we are all drawn to now, it’s almost like you weaken your brand when you change. And grow.”

In this evolving culture, many people are trapped inside their own identities because of patriarchy, heterosexism and traditional culture. But new forces, ani notes, are at play too. “Ones that discourage change and fluidity and inhabit that natural state of flux that I think living things want to inhabit,” she says.

During the summer of 1996, I spent time on a tree farm in Poughkeepsie, New York, owned by “Sexual Politics” author and feminist pioneer Kate Millett, who coined the phrase “The personal is political.” The Farm, as it was called, was created as a lesbian collective that offered artist space in exchange for trimming the trees or updating structures on the property.

While painting The Farm’s Blue Barn, Natalie (a gal from Nova Scotia whom I was sweet on) slipped “Imperfectly” into a battered tape player. We played that tape over and over, allowing the words of “What If No One’s Watching” to define that sliver in time.

If my life were a movieI would light a cigaretteAnd the smoke would curl around my faceEverything I do would be interestingI'd play the good guyIn every sceneBut I always feel I have toTake a stand

After the sun set and fireflies lit up around us, Natalie and I talked about walking the line of unpopularity. And we recognized the rage in our bellies as ani’s music fueled the late-night discussion.

Decades later, I tell ani how her lyrics and music gave me permission to examine my intense reactions to the complicated world around me.

Reflecting on her career decades later, ani tells me she found ways to process her fury. “I found a release valve. In my music and in my songs. Most of my rage gets turned on myself, most of it turns into sadness and tears.”

ani oftentimes found she makes great sacrifices to care for people around her. “I’m really like many, many, many other women. I’m going to generalize and say women, because I think generality has a deep truth to it.”

ani writes these stories because she struggles in the exact same way.

“So, sometimes it seems bitterly ironic that I should be able to liberate so many and not necessarily myself. But in other ways, it seems like that’s exactly,” she says, drifting mid-thought. “I hope I’m in line somewhere. I’m gonna get to me any day now.”

The music industry has completely revolutionized during ani’s lifetime, and yet it hasn't changed at all. Gigging as a teen, ani shopped homemade demo tapes to coffeehouses and bars to land stage time. Going from directly pitching herself to negotiating with corporate record companies, she was faced with a multitude of challenges.

“The old analog system: The record companies, the radio stations, the TV … was a very exclusive game,” she says. “And you had to get into that game to succeed. Until someone like me came along and proved otherwise.”

Instead of waiting on other people to make something of her, she created her own label — Righteous Babe Records — in 1990. The goal was to escape the clutches of the corporate music industry and independently release and control her own songs.

And while the music industry has transformed in many ways, artists today face just as many hurdles.

“When I was starting out, it was not any easier for artists, just different,” she says. “These days with the streaming platform, it’s no less exploitative.”

“The old model of the record company, at least when they got behind you, they got behind you. They would support you in certain ways while they exploited you. Now, [streaming services] say, ‘Just give me your shit, we’re not gonna help you make it at all, we’re not gonna help you promote it, we’re just going to exploit it more than ever.’”

Technology has allowed artists more access to people, the ability to self-record, even create a self-promoting YouTube channel.

“You can go from your bedroom to the world,” ani says. But in terms of the industry, and parlaying that into a career, she doesn’t see it as less abusive.

Righteous Babe Records rejects all of this. Its mission statement is “a people-friendly, sub-corporate, woman-informed, queer-happy small business that puts music before rock stardom and ideology before profit.”

The label currently represents almost a dozen artists. It also considers at least 17 as alumni, including the late Utah Phillips, a folksinger and ani’s former touring partner. And her personal catalog rises above 20 albums plus several live recordings and compilations.

With her music, ani has made a career out of living unapologetically on her terms. Early on, she even devised a three-year curriculum in high school so she could graduate a year earlier. Describing this move as rogue and genius, I tell her if she would have stuck to the four-year plan, she and I would have graduated the same year. (We were both born in 1970.)

Seemingly, out of nowhere, ani abruptly changes the subject.

“Ya know what’s funny? We’re both the same age … menopause!”

“It’s a thing that all people with ovaries go through, individually in the dark with no information, because that’s how patriarchy works,” she says. “I have been out there and trying to engage anyone and everyone about this thing that has now entered my life. This huge seismic thing that no one talks about that that no one seems to understand.”

Patriarchal powers have morphed dialogue about menopause into a negative experience, she says.

“I actually have found that I am asking menopausal people at every opportunity, do you experience feeling liberated from the 24/7 job of taking care of others? I feel a little bit freer to not feel with every ongoing heartache and stressor. Menopause made me able to breathe through it. I have been chemically, biologically released by mother earth from having to feel all other beings before me. It’s such a relief.”

Historically, menstruation has been shrouded in mystery, shame and mental illness.

"I’m sure to people without reproductive systems we seemed crazy. Why you got to react so much to things all the time? Well, that’s what it means to be an agent of creation,” she says, adding the transition to menopause has dramatically changed how she experiences the world.

And it has opened up a path to grounding her energy. At her home in New Orleans, ani spends a lot of time in her garden. “It literally brings me back to the earth.”

In recent years, she started a vegetable garden, and has added fruit trees.

“I have a mini-urban farm going. I grow hardy vegetables because I’m back to touring. They need to be able to sustain themselves when I travel. So, the hardy survive.”

ani also keeps her fingers in non-music creative projects, including writing children’s books and dramatic works. Her kids picture book “The Knowing,” which explores individual power and collective responsibility, is slated for release in March 2023. “I’ve been branching out like everybody in the pandemic, trying to figure out how to continue to exist in the new paradigm.”

After a lifetime of activism, and that cumulative perspective, ani pauses to contemplate the future.

“It’s very hopeful," she says, "if you can squint your eyes in the right direction.”