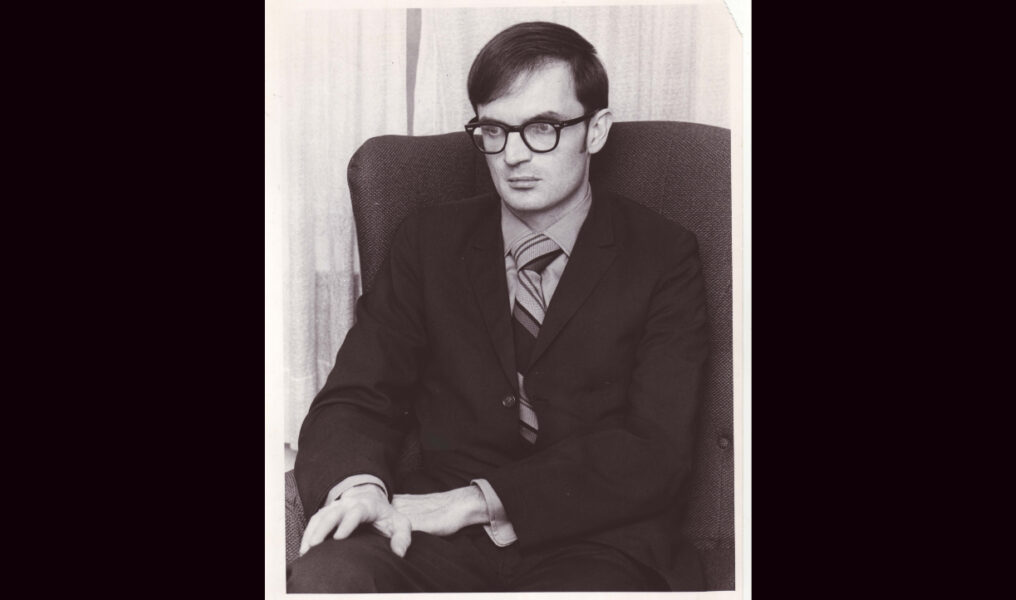

Remembering John Kavanaugh: An Unabashed Hellraiser Leaves One Helluva Legacy

Memorial set for Feb. 19 for pioneering Detroit LGBTQ+ activist

Early coordinator of the Detroit Gay Liberation Front, a founder of the Metropolitan Community Church of Detroit, and a constant gadfly for change within the Episcopal Church, John Kavanaugh died Dec. 17 at age 82. He had been in declining health for several years.

A memorial for the pioneering Detroit LGBTQ+ activist will be held at 2 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 19 at Zion Lutheran Church in Ferndale.

The retired autoworker dated his coming out as gay to a Saturday in 1970 when he stood nervously outside the flagship Hudson’s Department Store in downtown Detroit hawking a publication called the Gay Liberator.

He deliberately arrived a half hour late so he wouldn’t be the first activist there. “Everybody else was an hour late,” he recalled in a 1994 oral history interview. After waiting 15 minutes, he got up the nerve to start waving the newspaper to potential customers on his own. “I pulled a paper out of my bag and froze up against Hudson’s wall. And somebody came along, took the paper, put a quarter in my other hand, I put a quarter in the pocket, reached into the bag and froze up against the wall again,” he said. “Weeks later I was hollering, ‘Read all about it!’”

Kavanaugh was an unabashed hellraiser and a tireless champion of sexual and racial justice for more than five decades.

His legacy lives on in the form of numerous organizations he took part in or helped found, including the MCC Detroit, which marks its 50th anniversary as a sanctioned church in 2022. Meetings of the Detroit GLF Christian Caucus held at Kavanaugh’s apartment beginning in December 1970 led to the formation of MCC Detroit.

John Lawrence Kavanaugh was born Feb. 22, 1939 to Marian Kavanaugh, a homemaker, and Paul Kavanaugh, an electrical engineer with the Detroit Edison Company. He grew up in Dearborn and graduated with the class of 1957 from St. Alphonso High School. That following January he professed his vows with Brothers of Holy Cross, a religious order within the Roman Catholic Church.

After leaving the Brothers in 1965, Kavanaugh taught at Divine Child High School in Dearborn while pursuing his Masters at the University of Detroit. One evening he was walking in downtown Detroit with another teacher from school and the colleague pointed out with disdain a gay bar down a side street. “I was back there the next night,” Kavanaugh later recalled.

The bar was the Ten Eleven, one of the mainstays of local gay nightlife of the 1950s and ‘60s, where Kavanaugh found entrée into his community.

In July 1967, he moved into the northern part of the Virginia Park neighborhood, the same day as a police raid of a blind pig sparked the Detroit rebellion. The area, as he remembered it, consisted of homes owned by African American families, interspersed with apartment buildings with many of the units rented to white gay tenants like himself. The nearby Diplomat Lounge, operated by Bookie Stewart, became a regular hangout for Kavanaugh.

Around the same time, Kavanaugh took a job at Chevrolet Gear and Axle and worked on the assembly line for 25 years before taking an early retirement. He also discovered the city’s sole gay organization in existence in the late 1960s, ONE in Detroit, which offered support and fellowship to closeted men.

When the Detroit Gay Liberation Front (GLF) began in January 1970, inspired by the Stonewall Riots six months prior, Kavanaugh was an early attendee. He soon became coordinator and beside selling the Gay Liberator at Hudson’s, joined in demonstrations against the Episcopal Church and the Detroit Police Department.

Kavanaugh was pained by the exodus of people of color and lesbians when a majority of members voted to focus addressing only gay concerns. “Their contention was, single issue, let’s deal only with gay questions. Well, that’s a code word. What it means is let’s deal only with white male gay issues… Blacks, women realized what was being said and walked out,” he explained in the 1994 oral history. “These were friends that were walking out. It hurt very much.”

After GLF unraveled, he became involved with its successor group the Detroit Gay Activists. He and Ray Warner carried the banner for the DGA as marchers paraded down Woodward Avenue as part of Christopher Street Detroit ’72, the state’s first-ever Pride celebration in June 1972.

The following year, Kavanaugh was part of an entourage that took candidate Maryann Mahaffey on a campaign tour of gay bars in her first run for Detroit City Council, a seat she held for more than three decades.

Also in the early 1970s, Kavanaugh served as lay leader MCC Detroit during its formative years as a mission church, when it moved from his apartment to the finished basement of one of the members. “By the second meeting I was chosen to be their spokesperson, the term that we used, because I was out of the closet. Nobody else was,” he explained in a 2011 interview. Serving as the young congregation’s public face, he was interviewed by name in an article in the Detroit Free Press and appeared on Windsor television station CKLW to discuss MCC Detroit’s pathbreaking outreach to the local gay community.

In 1974, when a gay bar called Tiffany’s refused to serve John Pierre Adams, a Black friend who was serving as president of ONE in Detroit, Kavanaugh urged Gay Liberator readers to drink elsewhere.

“We are an outgrowth of Black Lib and of Women’s Lib. And when the gains of any are threatened, we all are,” he wrote. “When we ourselves do the threatening, then we are damn fools.”

A decade later, Kavanaugh became active in the Detroit chapter of Black and White Men Together. Through the years he remained an unyielding nag to church leaders in the Episcopal Diocese, offering critiques and pushing for change through an irregular personal newsletter called the Bead Reader.

By the early 1990s, he became close with Jeffrey Montgomery and volunteered with the Triangle Foundation, predecessor to Equality Michigan. He later shared his thoughts about Montgomery on film for the forthcoming documentary “America, You Kill Me.”

Kavanaugh remained politically and socially engaged. At age 65, he authored and published his first book, “Welcome to the Gay Age,” which drew linkages between laws against interracial marriage and laws against same-sex marriage. Kavanaugh believed people in intimate queer relationships that bridged racial boundaries offered expansive opportunities to liberate faith and society.

In 2018, Kavanaugh donated his home at 135 Hazelwood Street to the Ruth Ellis Center to serve as a haven for lesbians and queer women and girls. At Kavanaugh’s request, the new venue was named Kofi House in honor of activist, clinical psychologist, and REC co-founder Dr. Kofi Adoma.

As an activist and thinker, Kavanaugh could be idiosyncratic and insistent. In many ways, as his body grew frail in his later years, his sass only grew stronger.

Many who knew him personally or knew him from any number of meetings bore witness to his salty language. As he said in a letter to Metra magazine in 1985, “I am my mother’s mind and my father’s cuss words!”