The Stonewall uprising had reverb.

Multiple nights of rioting against police in June 1969 sent shockwaves across the country and sparked gay organizing on a mass scale. A new, radical group in New York called itself the Gay Liberation Front, the "front" from the National Liberation Front, another name for the Viet Cong. Fervent demands for freedom supplanted polite pickets asking for rights.

The combustion of Stonewall was seemingly spontaneous, yet reflected a lot of pent-up rage. Many gay activists had already become emboldened by 1969. More militant ideas and feelings were already percolating.

They were volatile times. New Left rebellion, Black Power and a feminist resurgence were all in the air as opposition to the Vietnam War reached new heights.

In part a form of generational rebellion, in part a community coming out and into its own, Gay Liberation in Michigan left a lasting, largely untold legacy.

Michiganders now understood that under the rubric LGBTQ they felt galvanized to come out and to take action. Some were motivated by ire at the straight strictures of society, some wished to be honest, some understood visibility as a key to asserting political and social change.

Yet while the years from 1970 to roughly 1974 marked major transformation, the turning points and individuals that made a difference have too often been forgotten.

"I was typing up the Sunday church bulletin in December of 1969 and on the calendar, I see a note that says, 'Gay Meeting.' So, I go to the priest … and I said, 'Daddy-o, what is this gay meeting thing?' And he said, 'I don't know what it is. One of the guys in the draft resistance group said. 'Can we have a gay meeting here?' And I said, 'Well, whatever that is, if we can't have a gay meeting here we might as well shut this God Box down!'"

—Jim Toy interviewed for the OutWords Archives.

MSU Gay Liberation Movement. Photo from Greg Kamm.

Foundings

The origins of Gay Liberation in Michigan can be traced to a personal ad.

In October 1969, months after Stonewall and long before Grindr and other apps made meeting online a routine part of same-sex dating, a factory worker named Wayne King placed an ad in an anti-establishment newspaper called the Fifth Estate: "Gay radical, 27, wants to meet same 18 to 30. Masc. only. Box 631-A, Detroit, 48232."

Within weeks King changed the ad. "Those interested in forming a 'gay liberation' group write Box 631A…" An initial meeting was set for January 1970 at St. Joseph Episcopal Church.

Within a couple of months, according to minutes Jim Toy took as meeting secretary, 50 people on average were coming to meetings. Attendees reflected the city, multiracial, cross-cultural, co ed. Most were in their 20s. They initially called themselves the Detroit Gay Liberation Movement but soon decided on the Detroit Gay Liberation Front.

The statewide activism initiated by the Detroit GLF included raps, zaps, dances, a gay switchboard, newsletters, classroom outreach and a bail bond fund. It also came to encompass lobbying and old-fashioned electoral politics.

Gay Liberation in Michigan gained its strongest foothold in three main centers of gravity, Detroit, Ann Arbor and the Lansing area. GLFs also formed in Battle Creek, Kalamazoo and Port Huron.

In March, Toy and others decided to start a group in Ann Arbor and without qualm embraced the name Gay Liberation Front. Activists at Michigan State adopted a less antagonistic moniker, launching the Gay Liberation Movement in April 1970.

Campuses, in particular, became hotbeds of gay activism. Besides U-M and MSU, early campus organizing began in 1970 and 1971 at Central Michigan University, Eastern Michigan, Grand Valley State, Wayne State and Western Michigan.

At the same time, Gay Lib groups met with resistance from the highest levels of university administration. In May 1970, when the Ann Arbor GLF sought to hold a Midwest conference at U-M, university president Robben Fleming denied use of school facilities. Student leader Jerry DeGrieck, who had keys to the Student Activities Building, snuck GLF in and they held the conference anyway.

Two years later at MSU, university officials refused to allow the GLM to hang a banner at the Abbot Street entrance for Gay Pride Week. Word got back to the GLM that Vice President Jack Breslin did not want to advertise a club for men engaged in oral sex "on his campus," only his language was reportedly more offensive.

Rivalries and differences of opinion led groups to fold and new groups to emerge over time. The Detroit GLF gave way to the Detroit Gay Activists. Political divisions eventually ruptured the DGA, with one faction focusing on the Gay Liberator newspaper and another forming the short-lived Motor City Alliance of Gays.

Lesbians on Their Own

The West Michigan Gay Alliance in Grand Rapids was notable for having lesbian leadership and strong female participation but was an exception among Gay Liberation groups in the state.

In other instances, women came out through feminism and many sought to organize on their own.

Trudi Sippola arrived at MSU from the Upper Peninsula in 1971, her first time away from home. In a recent phone interview, she explained how she found the campus Women's Center and became involved there despite being warned she'd "run into lesbians."

She thrived in the large consciousness-raising groups and from highly politicized dialogues, drafting political statements and developing lesbian-feminist theories to put into action. "I was in a pretty radical state of mind," she said.

At some point, Sippola realized she found some of the other women attractive.

She accepted an invitation to a lesbian gathering, where someone invited Sippola up to her bedroom.

"I didn't know you were gay," the woman said to her. "How long have you been out?"

"About 20 minutes," Sippola replied.

She soon moved into lesbian communes. In one small lesbian house she lived in, they displayed a large woman's symbol and fist as a taunt to the fraternity across the street.

Sippola was vaguely aware of Stonewall and had little interaction with the MSU GLM. For her, the early 1970s were important as a time for lesbians to get together on their own.

Organizations expressly for lesbians that emerged at the time included the Detroit Daughters of Bilitis, which met at Gay Whiteside's home in Dearborn Heights, the Radical Lesbians followed by the Gay Awareness Women's Kollective in Ann Arbor and the Purple Perils in Lansing.

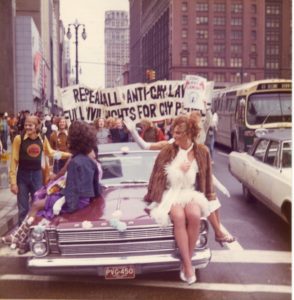

Christopher Street Detroit '72 march. Photo from the Gay Liberator.

New Visibility

Gay Liberation in Michigan and elsewhere entailed a new definition of coming out. As historian John D'Emilio notes, before Stonewall coming out meant coming out into the gay world. During Gay Lib, coming out came to mean coming out to everybody.

On April 15, 1970, at a large anti-Vietnam War rally in Detroit's Kennedy Square, Jim Toy became the first person to publicly come out as gay in Michigan.

As revealed by Detroit Red Squad files, a heated battle ensued during planning for the rally over whether to let someone from GLF speak.

Lincoln Park native and anti-war activist Kirk Essler was at the planning meeting. Speaking by phone last month, he recalled having told a few close friends he was gay, but GLF's demand for a speaking slot impressed Essler to the idea of gay politics. He soon met Detroit GLF member Ken Dudley and later became active in the Wayne State GLF, coming out in an op-ed in the South End.

Christopher Street Detroit '72, a week of events to commemorate the third anniversary of Stonewall in 1972, might be considered an act of collective daring. The celebration culminated with Detroit's and Michigan's first-ever Pride march. About 200 participants crowded a single lane of Woodward Avenue from Cass Park to Kennedy Square.

Susan Swope, who wrote for the Gay Liberator under the name Susan Williamson, was the sole woman to speak at the rally. Still heterosexually married while she increasingly embraced her lesbian self, she worried her in-laws would see her on television.

"I thought I just have to do it. It's important, and if that happens it happens. And I remember standing up there and delivering that speech and being really nervous," she said in a 2011 oral history. "But of course, in the event, what got on TV was the drag queens. That's who always gets on TV when you have a gay march."

There were television cameras that roved around. I do remember that they picked out this guy in elaborate drag, the full gown, the full bit. And, of course, they asked him first, "Are you willing to be interviewed?" He said, "Yes." So, the question came, "Tell us your name and where you work." And in this deep bass voice, he said, "My name is Charles Johnson and I work at Ford's." So, working-class gay men in Detroit were proud and assertive in a period when the gay movement was largely student based and often looked down on working people…

—Christopher Z. Hobson interviewed for the LGBTQ youth public radio program "Outcasting."

Media Breakthroughs

On local television, homosexuality was a novelty, an object of amusement, and something to garner ratings. Detroit GLFers Sunny King, Ray Warner, and Ken Dudley all appeared on The Lou Gordon Show, a program that relished controversial topics. Warner's family was so upset by his revealing his sexuality, that he began using Ray West as his movement name.

Alternative newspapers like the Fifth Estate, the Ann Arbor Sun, and Joint Issue in Lansing covered gay activities with more seriousness. The mainstream dailies took notice, too. In October 1970, the Detroit Free Press Magazine did a lengthy report on "The Homosexuals of Detroit." Four years later, in November 1974, the Free Press Magazine ran a feature "Gay Women of Detroit."

Gay Lib activism was all over student newspapers, from the Michigan Daily at U-M, the South End at WSU and the Lanthorn at GVSU to the Eastern Echo and the Oakland Forward.

Gay people began to produce publications of their own, as well, such as the Gay Liberator, Gayzette, and Gayscene. In Lansing, a gay newspaper called Sunflower lasted two issues. The Revolutionary Lesbians in Ann Arbor, for whom the Radicalesbians were not radical enough, published Spectre. It lasted six issues.

Starting in 1973, Gayly Speaking added gay and lesbian voices to the airwaves of WDET-FM.

Protests

The Ann Arbor GLF seemed most eager to take to the streets. In its first action, the group demonstrated in support of the campus Black Action movement. During the dispute with U-M president Fleming, burly GLF member Harry "Kitty" Kevorkian in drag crashed a formal tea held at the president's home.

An October 1970 FBI memorandum, later released under the Freedom of Information Act, outlined secret surveillance of the group.

"It is to be noted that the above-captioned organization is small in number and ineffectual," an unknown agent reported.

In November 1970, when the Ann Arbor GLF and the Detroit GLF demanded to address the Episcopal Dioceses convention about the eviction of the GLF from St. Joseph, church leaders gaveled the convention to an early close.

For the Detroit GLF, decades of police harassment of gay men provoked much of their attention. In January 1971, 25 GLFers staged a demonstration in 5-degree temperature at the Murphy Hall of Justice. In April 1971, the group picketed the Detroit Traffic Court to protest the arrest for alleged homosexual soliciting of Michael Fylstra, one of the few local gay men willing to challenge police entrapment.

Detroit Gay Activists demonstrated against Hudson's downtown and at Oakland Mall in January 1972 for colluding with police who apprehended men cruising the department store's restrooms.

In September 1972, the Ann Arbor GLF picketed the Flame Bar for excluding transsexuals. A month later, the Michigan Gay Confederation, a coalition of groups from around Michigan, marched on the state capitol against Traxler Bill, which would have decriminalized sodomy, because legislation would have made no change in laws against cross-dressing.

Perhaps most disruptive, the MSU GLM helped instigate shut down of Grand River Avenue in May 1972 to protest continued U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

As Leonard Graff recalled in a 1994 oral history interview, GLM member Don Gaudard pretended to drop a contact lens in the middle of the intersection, it was Grand River and M.A.C. Several people scurried to the ground pretending to look for the contact, stopping traffic.

"A small crowd got to be a bigger crowd. 'What's going on?' 'What's going on?' 'We're just looking for a contact lens,'" Graff explained. "'Then, 'OK, let's sit down. We're going to have a blockade.'"

The next thing you know, people are dashing off to get some friends and the streets were just filled with protesters. And we brought Michigan and Grand River to a stand-still for days. For days."

We must realize that although some of us feel comfortable and believe ourselves to be liberated, as long as we quietly allow "other homosexuals" in "other places" to be arrested for inviting someone to bed or for cross-dressing; as long as we ignore the lonely desperation of other gays who feel like degenerates because of the need to love; as long as we allow any gay anywhere to be oppressed or discriminated against in any way — that not only are we perpetuating gay oppression by our complacency, but we ourselves — no matter how safe we feel — are in jeopardy.

—West Michigan Gay Alliance newsletter.

Creating Community

Gay Liberation succeeded in fostering new, often lasting Institutions outside of bars and private friendship networks. Among these was the Metropolitan Community Church of Detroit, which came into being out of the Christian Caucus of the Detroit GLF.

MCC Detroit members chose not to take part in gay pride picnic in June 1972 for fear the FBI would be watching. However, in July 1973, under Pastor Tony Clemente, the congregation held a memorial service and benefit that raised $800 for victims of the arson attack on the Upstairs Lounge in New Orleans.

In November 1971, U-M hired Cyndi Gair from the Radicalesbians and Jim Toy from the Ann Arbor GLF as Human Sexuality Advocates, what today is the Spectrum Center, the first such office in the U.S.

In June of 1972, the Green Carnation Community Center opened at 660 Virginia Park in Detroit. Later that summer, activists in Lansing launched a community center in a rented house at 117 S. Pennsylvania and the West Michigan Gay Alliance began a community center at 129 Fulton S.E. in Grand Rapids.

Similarly, Geneva House at 97 Geneva St. in Highland Park, a commune originally begun as the Geneva Street Theater House until the last of the straight residents moved out, served as a sort of community center for Detroit's lesbian community into the mid-1970s.

However long- or short-lived these centers were, they embedded the idea of needing collective space to gather as a community, an idea that endured.

Internal Contention

From the earliest manifestations of Gay Liberation in Michigan, activists expressed genuine affinity and kinship. They sought solidarity and felt solidarity. Yet many did not always earn solidarity.

Those who fell short were not so sensitive to multiple forms of oppression, or the realities of discrimination targeted at people for being women, gender non-conforming, black, Chicano or Chicana and Native American.

The still familiar fault lines of race and gender took a toll.

The Detroit GLF picket of the Murphy Hall of Justice precipitated the exodus. Most of the Black Gay Caucus left the group in anger because the protest statement emphasized police homophobia while omitting police racism.

The upheaval left John Kavanaugh with a feeling of devastation.

"Their contention was: single issue. Let's deal only with gay questions. Well, that's a code word. What it means is let's deal only with white male gay issues. Blacks and women realized what was being said and walked out," recalled Kavanaugh in an oral history recorded in 1994. "I was chairing the meetings when they walked out. And frankly, these were friends that were walking out. It hurt very much"

Ken Dudley was the only person of color to address the Christopher Street Detroit '72 rally. His speech encapsulated the chasm and insult felt among many local gay African-Americans.

"There are many black gays who are not marching with us today," Dudley said. "That may be explained in part by the idea that black gay people march every day. If not by virtue of their gayness, then surely by virtue of their blackness."

The "masculine only" preference in Wayne King's original Fifth Estate personal ad reflected another fissure in the Michigan movement. In the Gay Liberator, A. Michael Weber repeatedly challenged negative attitudes toward transexuals, the term then in use.

"Other gay people should realize transexually-oriented people have long been the most isolated of all for most of their development," Weber wrote.

Sexism seemed particularly glaring and rarely acknowledged among gay men. Merrilee Melvin, who was hired to organize events for Christopher Street Detroit '72, felt detached working with them.

"I remember being in a room with a lot of gay men but sitting almost in the middle in this chair off by myself, trying to tell the men what it felt like being a woman working with them and not being heard, not being taken seriously, not being seen," Melvin shared in a 2011 oral history. "I remember being in tears. And I remember them looking puzzled at what everybody was talking about, too. It was hard. … Because it's like the gay men were my gay brothers."

Lesbian activists from around the state confronted their gay male counterparts about the sexual divide at a meeting of the Michigan Gay Confederation in September 1972.

The sisters from Ann Arbor, Lansing, East Lansing, Grand Rapids and Detroit are unified in their strong convictions about protecting women's rights within this Confederation. We are not going to allow the men to ignore our constituency. We can see no future in this Confederation as long as sexist attitudes continue to exist.

We are here today to voice our opinions and plans of action as women and Lesbians. Our primary aim is to end sexist attitudes, especially here in the gay community. In order to support this Confederation, you must join in our struggle to end this sexism.

—Statement to the Michigan Gay Confederation as published in Her-Self. MGC unraveled shortly thereafter.

Kathy Kozachenko. Photo from the Ann Arbor Sun.

Lasting Achievement

Despite tumult and burnout, Gay Liberation in Michigan yielded some significant accomplishments.

In March 1972, East Lansing barred discrimination against gay people in city hiring. In July 1972, the Ann Arbor City Council enacted an ordinance prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment, housing, and public accommodations. In May, East Lansing followed suit with its own ordinance, though its did not cover housing. In November 1973, Detroit voters approved a new city charter that prohibited discrimination city-wide based on sexual orientation.

Gay Lib activists instigated these reforms, putting Ann Arbor, East Lansing and Detroit among the national gay vanguard, models for other cities.

The years to come would show whether these were true achievements or gestures of begrudging tolerance.

Elective office, too, suggested slowly evolving attitudes.

In 1972, Don Gaudard ran as an openly gay candidate for the East Lansing School Board. A year later, Connie McConnohie ran as an out lesbian for the Detroit City Council. Both lost. McConnohie's rift with local Gay Lib activists, her prison record, and her campaign slogan "Put a Real Man in Common Council" likely contributed to her loss. Gaudard and McConnohie nonetheless set an example.

Nancy Weschler and Jerry DeGrieck hold the distinction of being the first openly gay elected officials in the country. They weren't out when they were elected to the Ann Arbor City Council in April 1972 on the Human Rights Party ticket. Rather, they came out at an October 1973 council meeting when their colleagues refused to act on complaints that the Rubaiyat disco refused to allow women to dance together.

Human Rights Party candidate Kathy Kozachenko, in April 1974, became the first openly gay candidate to be elected official in the U.S. when voters from Ann Arbor's Second Ward elected her to the council. It was a game changer. On election night, she told her supporters, "Many people's attitudes about gayness are still far from healthy, but my campaign forced some people at least to re-examine their prejudices and stereotypes."

Coming out, telling people you were gay, was a hard thing to do in 1973. We lived in a society that still considered gays to be sick. Being openly gay meant risking your job and perhaps losing friends. It often meant harassment by the local police, being excluded from public accommodations, or being physically assaulted. When Jerry and I revealed that we were gay, it caused a stir on the Council and in the city. The other Councilors became more hostile. The mayor told Jerry he was 'sick' and he told me that I 'took the cake.'

—Nancy Weschler quoted in the book "Radicals in Power."

With the end of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, and President Richard Nixon's resignation from Watergate, political fervor began to wane after 1974.

In terms of gay and lesbian activism in Michigan, Brian McNaught, Sappho Sisters Rising, Lesbian Connection and the Leaping Lesbian, the Association of Suburban People, Metro Gay News, Nancy Wilson at MCC Detroit, the founding of the Michigan Organization for Human Rights in response to Anita Bryant, the Lansing Association for Human Rights, Moonrise in Flint, Lavender Morning in Kalamazoo, various chapters of Dignity and the Gay Community Services Center in Ann Arbor all took the movement in new directions.

Emerging from the shockwaves of Stonewall, Gay Liberation in Michigan, in turn, had reverb of its own.

© Tim Retzloff

Tim Retzloff teaches history and LGBTQ studies at Michigan State University. He is nearing completion of his first book, Metro Gay: City, Suburb, and the Changing Map of Queer Detroit.

Dr. Retzloff will be discussing Gay Liberation in Michigan at three upcoming public talks:

Saturday, June 22 – 6 p.m.

Ann Arbor District Library, Westgate Branch

2503 Jackson Road, Ann Arbor

Tuesday, July 10 – 6:30 p.m.

Salus Center

408 S. Washington Square, Lansing

Thursday, Aug. 15 – 6 p.m.

Detroit Historical Museum

5401 Woodward Ave., Detroit