The Dark Side of Advocacy, According to This Leading Michigan Trans Advocate

For Julisa Abad, her life and work intersect in challenging ways most people don't consider

On July 31, 2021, I woke up feeling so grateful for another day, but this day was an especially important one. That night, I would be acknowledged with a Humanitarian of the Year award for the work I do, presented by Motown Honors. I’ve received many awards for the strides I've made for the LGBTQ+ community, but this one felt different — it felt like the first time I'd really been seen by my peers. That night at the awards ceremony, I wore a red dress and sat at a table with my colleagues and my best friend Ashia Davis, excited and a little nervous about the evening ahead of us — but let's go back a little to understand how I got here.

I was born into a middle-class Latin family, and I knew at 6 that I was different. I didn't know what that meant then, but by 15, I identified with being transgender. I had dreams of becoming a flight attendant or a fashion designer. At 18, I left home to be able to truly be my authentic self, and in 2016, I relocated to Detroit, specifically the Six Mile and Woodward area. After one week, I realized it was the concrete jungle, where all demographics and different identities do survival sex work, and that this part of Detroit is known for crime. Like many trans people, particularly trans women of color, I couldn't gain employment anywhere due to the social stigmas — at the time, gender identity and sexual orientation were not protected by the Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act.

Later that year, when I saw our prosecutor Kym Worthy and our now attorney general Dana Nessel on TV forming the Fair Michigan project, which combats crimes against the LGBTQ+ community, I knew I wanted to be involved. We started in Wayne County in 2016.

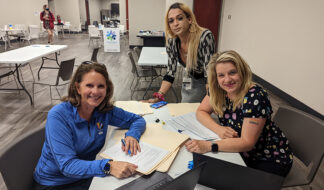

At this point, we have prosecuted more than 41 capital cases with a 100% conviction rate. We have expanded to Oakland, Washtenaw and Ingham counties, and we are the first in the nation to have a trans inclusion policy. Myself and our special prosecutor Kam Towns have trained several police precincts in Detroit on cultural competency. I have trained the Wayne County Sheriff's office on how they house trans individuals. I’ve also spearheaded a name change program for trans people through Ford, GM and the Dykema law firm. To date, we have helped 321 trans people living in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb County legally change their name with no cost to them. We have partnerships with the University of Michigan where we run a program helping people access legal services and a trauma-informed program focused on trans women of color.

I'm so humble and grateful for my role and what I've been able to accomplish, but there is another side to advocacy work that we never discuss — a darker side.

Like most trans people, I ultimately had to leave home to be able to be my authentic self. For 15 years, my father didn't speak to me. I moved to Detroit to start a new life, not knowing what my calling would be. I started advocating because of the lack of respect, resources and opportunities for myself, but also for my community.

Today in 2024, we are so much more progressive than when I started this job, but the reality is that in 2016, there weren’t many opportunities for trans women. My advocacy propelled me onto TV, launching me to the forefront of the trans advocacy movement and presenting me as a pillar of my community. But it’s important to remember that for all the people who love me because of the work I do, there are just as many trans women you don’t see because of reasons we don’t often consider — opportunities, colorism, classism, passability or simply the fact that sometimes there's only space for one person, which creates a rift in my community.

When you’re placed on a pedestal, you’re held to a higher standard. I always have to be “on.” I can never have a bad day because I'm in the public eye, and every event I'm at is always publicized, which gives me the worst anxiety.

I work with more than seven partnerships and have a hard time saying no, even when I'm depleted because I know this work has to get done, and if not by me, then who? I do not get to go home and turn it off, unlike a lot of my colleagues. I’m part of this community; I see my fellow community members in my free time, and they call me as a point of contact. It’s constant. If I want to go out and get my hair done, my experience is different because I'm Julisa the Advocate.

Maybe most difficult of all, the work hasn’t allowed me the time to grieve properly after losing the first person I was ever in love with to a murder in the Palmer Park area in 2016 — the same year six other trans women of color were murdered. Though things are different today and we have made strides, the epidemic of violence against trans women of color continues. On June 1, 2023, the first day of Pride, Ashia Davis, my best friend of 10 years, was murdered in her Highland Park hotel room. The killer is still on the loose.

When people see me now, they often focus on what seems like the finished product — my stable job and nice purses, the image of me on TV and in the courtroom doing advocacy work as Michigan’s leading trans advocate. What they often forget is the homelessness, survival sex work and the struggles I once faced trying to find stability, employment and medical insurance. There is not a day that goes by that certain facts don’t cross my mind: Every Civil Rights person I admire or who has made astronomical changes for the Black and Brown community has been murdered. And, according to some studies, the life expectancy for a trans woman of color is 35 years old.

I'm so proud and grateful for the strides we have made and will continue my work, but the next time you see a community advocate, please stop and give them a hug. You never know what we are internally going through — the things we don't allow our community to see.