Why Do All My GOP State Reps Support the Trans/Gay Panic Defense?

Party discipline is one thing, but what’s their objection? They won’t say why they support dehumanizing LGBTQ+ people.

Before I write about the trans/gay panic defense and how U.S. states are gradually passing laws against its use in court, and before I write about how Republicans in my home state of Michigan just voted unanimously to keep the practice legal, I have to tell you a story about my own life. I won’t take long, but I’ll tell you what … it’s hard to appreciate some issues without empathy, which in my opinion thrives best with personal storytelling.

I pushed away from Ken’s sour beer breath and BO. We were sitting on my bed in my Air Force training-school dorm room, both of us in our early 20s. He wiggled in closer. And closer. Pretty soon, his lips were almost brushing mine, again. I felt nauseated. I liked Ken, but he was seriously drunk, and I was seriously not attracted to him even when he smelled good and could string words together into actual sentences.

“Stop it!” I said. “You need to go home, OK? Just because I’m gay doesn’t mean I want to make out with every man in the universe.”

I politely walked him to the door and watched him bounce off walls toward his own room, keeping watch until I was sure he wasn’t headed outside into traffic or whatever.

Think I’ve made my point? I haven’t yet.

Flash back a couple weeks, and Ken (not his real name) was one of four or five people sitting around my best friend Mark’s dorm room — drinking, listening to music, solving all the problems of the world together like only young people can do. That room and those people would soon become very special to me, because I could be free to be me.

I had already come out as gay to Mark, alone.

Telling him opened up our friendship to a new, deeper meaning, and I craved more of that genuine honesty and trust. I was so tired of hiding. So, I decided that with Mark’s help, I would come out to our closest friends. That was a big deal then, and I was scared.

When the big night came, we lounged in Mark’s room passing around a bottle of single-malt scotch. He waggled his eyebrows at me a couple different times when the conversation lagged, and finally I cleared my throat and said, “Guys, I’ve got something really personal to talk about.”

I’ll spare you the boring details of my halting early-1980s coming-out speech, but I want to share reactions. Mark’s girlfriend jumped up and hugged me, whispering into my ear, “Nice job! And about time.”

A couple guys looked uncomfortable but stuttered out vaguely kind words, which I took as a win. Then an avalanche of questions started, the bottle started getting passed around again, and we all lightened up and had a good time.

Except for Ken, who had all but stopped talking.

He stood up at one point to change the music, and when the room went silent for a second, he said, “I don’t mind at all that you’re gay. Just don’t hit on me. I’d hate to have to beat the shit out of you.”

He laughed, hit a button, and AC/DC crashed into the gash he’d ripped in the air.

I turned to see Mark laughing too. His girlfriend shook her head almost imperceptibly at me, like she was saying, “I hear you, but leave it alone for now.”

She and I argued with Mark after everybody else left. “Come on, guys,” he said. “Ken wasn’t serious about beating anybody up, obviously, and you have to admit, a gay guy hitting on a straight guy is gross. You never know what might happen.”

Well.

I loved Mark like a brother for many years, but that was not his finest moment. It was the zeitgeist, though. Saying, “I’m fine that you’re gay as long as you don’t hit on me” was like some mandatory thing guys said.

All. The. Time.

Did it make me feel as low as gum stuck to the bottom of somebody’s shoe? Betcher ass. Like, being gay makes me presumptively unable to respect personal space and/or flirt appropriately? Being gay is so disgusting that if some dude asks you out by mistake, you reserve the right to get violent? What even is that?

Mark apologized a few days later after he’d had time to process because he was (is) a very thoughtful person. Not long after that was when Ken tried to kiss me, I felt grossed out and asked him to leave, and then I watched carefully to make sure he got home safe.

Now I’ve made my point.

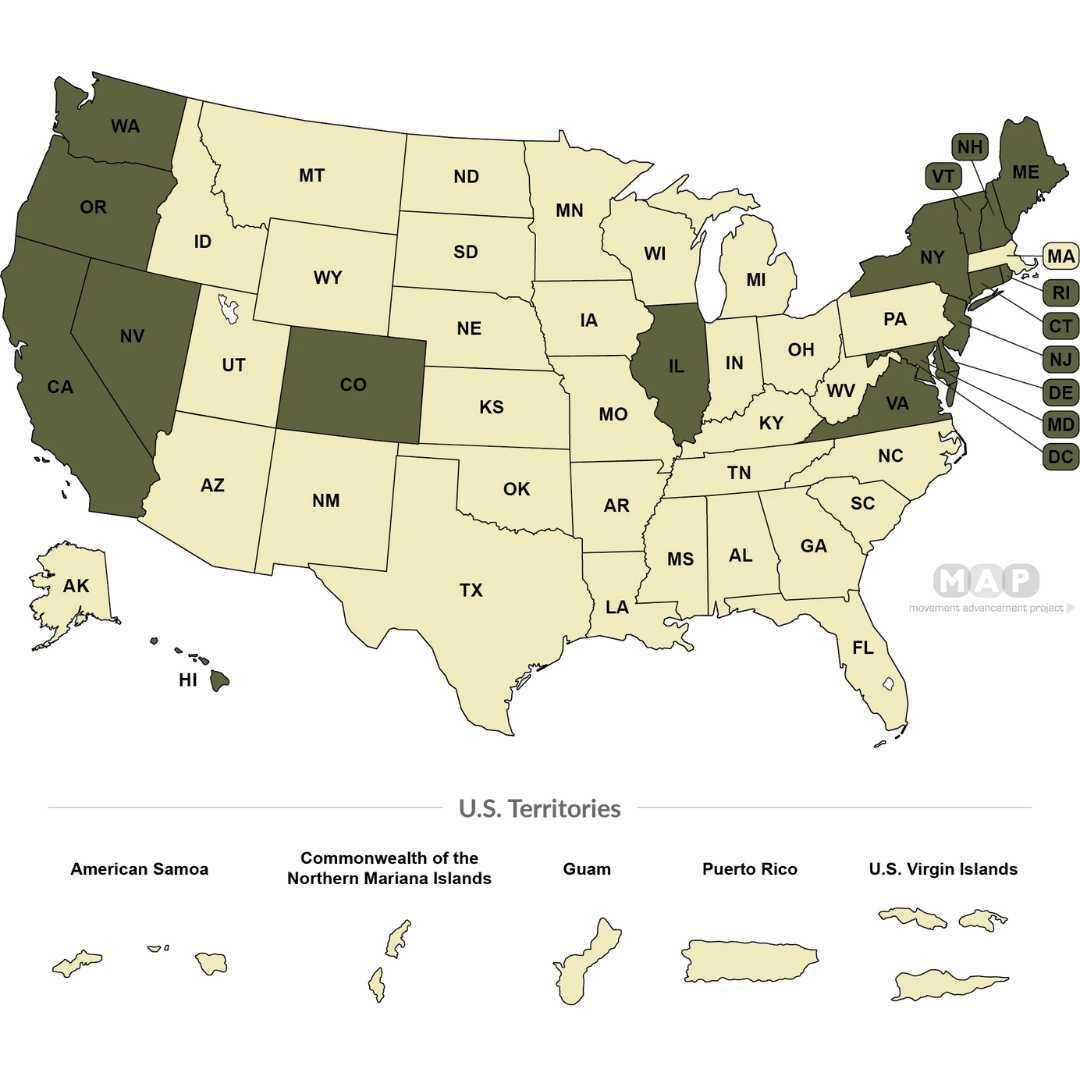

According to Movement Advancement Project, the states above in tan allow criminal defendants to argue for lighter sentences because their victims were trans or gay. The 17 states in green do not. My home state of Michigan may soon join those green states.

So, let’s talk about the so-called trans/gay “panic defense”

Haven’t heard of it? According to UpNorthLive, “The ‘gay/trans panic’ legal defense allows a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity to be used as a justification for why a defendant violently attacked their victim.”

That’s a pretty succinct definition of a phenomenon I’ve been hearing about all my life. Somebody beats up or kills an LGBTQ+ person, then their lawyer argues to a jury that they deserve a lighter sentence because of their supposed shock learning a potential sex partner was queer.

“That gay guy came onto me, and I was so freaked out I snapped. I’m sorry I lost it, but please take those mitigating circumstances into account.”

Or.

“When I realized she was a really a he, I was so disgusted I lost control of myself. I should not be held fully legally responsible for my actions.”

According to Michigan House Speaker Pro Tempore Laurie Pohutsky (a Democrat who identifies as bisexual), the defense is “usually used in conjunction with other defenses as a way to play on unfortunate prejudices in an effort to lead to lighter sentences.”

Michigan is one of 33 states that still allow the defense, and Pohutsky told UpNothLive that needs to change, specifying that the practice treats LGBTQ+ victims as fundamentally less deserving of justice: “The root of the matter, the whole defense is based in the thought that trans and LGBTQ folks are less human than other victims…”

She says the problem is a lot bigger than many people realize, because it’s used a lot more than people realize. She adds that the general public often don’t understand how vulnerable many queer people are. To illustrate, she says the defense is most common in Michigan in cases where Black trans women have been assaulted or killed.

Julisa Abad agrees. The director of Transgender Outreach and Advocacy at the nonprofit Fair Michigan, Abad identifies as Black, Hispanic and transgender. She’s been fighting for genuine justice in this area for many years.

Abad tells UpNorthLive, “African-American men rather love us in private and kill us in public than have anyone know of their association with trans women. It happens all the time, but it also happens because of the lack of education and how we villainize people as a community for being enamored with trans women.”

She adds that the defense is most often used when Black trans sex workers are attacked and adds that “I’m going to continue to live the good fight.”

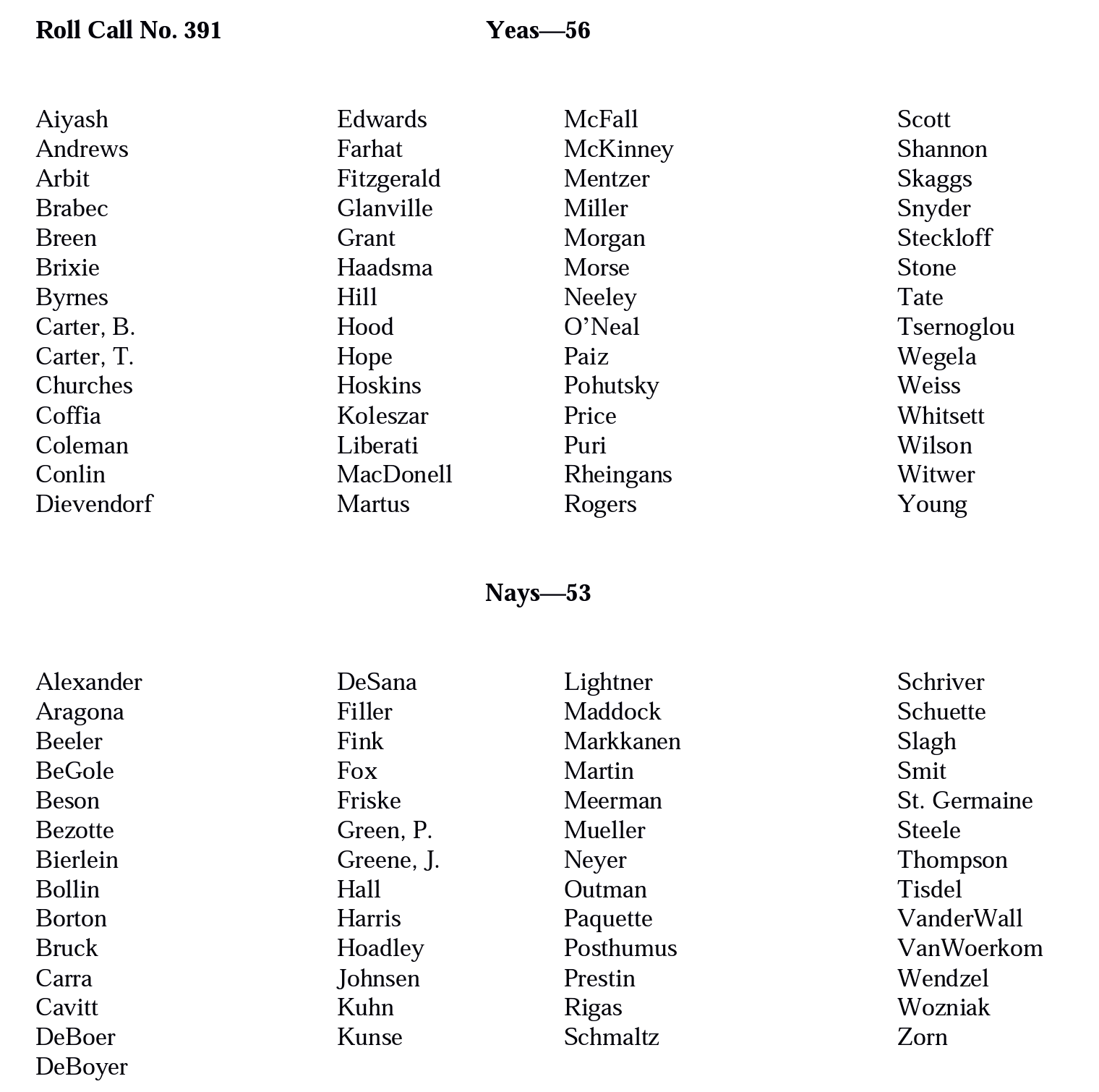

It looks like she’s about to celebrate quite a victory. The Michigan House voted last week to approve a bill banning the defense outright, and with a Democratic majority in the Senate and a Democratic governor, the bill is seen as likely to become law this year. Still — I’m puzzled and saddened by total Republican opposition.

When the bill passed on Oct. 19, every Democrat in the House voted for it, and every Republican voted against it. Most puzzling is that the Michigan GOP hasn’t released a statement explaining why and neither has any individual Republican lawmaker. In fact, Speaker Pohutsky says “several” Republican lawmakers have told her privately they support the bill’s aims, but they still wouldn’t vote for it.

Does that make me feel less than human, as Pohutsky suggests? Sure it does. I think back to that night with Ken. He didn’t touch me. He didn’t assault me, sexually or otherwise. He was an obnoxious, sloppy drunk who had obviously been repressing his own gay or bisexual attractions, and his unwanted advances repulsed me.

What if I’d punched him? I’d have had no excuse for violence, right? I think that’s obvious.

But what if he really HAD kissed me against my will or groped me? What if I’d punched him under those circumstances? What kind of legal defense should I have used? Would a gay panic defense have been appropriate?

Not only would that defense have been dehumanizing, I wouldn’t have needed it! I could have just told a jury the truth: that Ken sexually assaulted me and I was defending myself. “Please take the sexual assault he committed into consideration when assessing my guilt or deciding how to sentence me.”

Any defendant can make an argument like that when the facts support them. After the Michigan panic defense ban passes (if it does), any defendant could STILL make an argument that they deserve mitigation because they were assaulted, if they were assaulted.

What they won’t be able to do is say they should be treated extra leniently because their victim is transgender or gay. Doesn’t that seem entirely fair? Shouldn’t all criminal defendants be judged by the same standard, regardless of their victim’s gender identity or sexual orientation? Shouldn’t all victims be afforded equal protection under the law?

To me, Laurie Pohutsky, Julisa Abad and every Democrat in the Michigan House, that just seems obvious. I guess it’s not obvious to the Michigan GOP, and I wish I knew why.

I’d like to think it’s not because of the reflexive opposition to LGBTQ+ equality that’s been exploding around the U.S. since Donald Trump was elected in 2016. Honestly, though, I can’t think of any other reason that defendants convicted of violent assaults should be able to argue for a lighter sentence because their victim is queer.

Can you? Asking for a friend.

This article was reprinted from Medium.com with permission from the author.