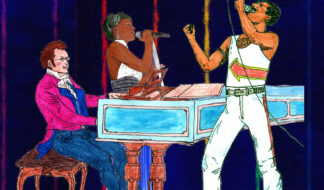

Madelyn Poirter, Dan Johnson and Greg Trzaskoma in "The Best of Enemies." Photo: UDM Theatre Company

Discussions of race and racism in modern-day America are fraught with danger, as emotion and passion often trump civility and reason, and political correctness and the fear of being called the dreaded "r-word" stifle an honest and open discourse. Even reviewing a play about racism is like stumbling onto a minefield, as my interpretation of the production might set off an explosive debate with other attendees whose personal experiences and biases might differ from mine.

But such is life.

Yet I suspect one area of agreement I'll have with others at the University of Detroit Mercy Theatre Company's opening night performance of "The Best of Enemies" is this: It was one heck of a thought-provoking night of theater.

Based on the true story of the "unlikely friendship" that emerged between a black activist and an exalted cyclops of the Klu Klux Klan, "The Best of Enemies" recalls the pain and division the residents of Durham, N.C. faced when the federal government came to town to force their schools to desegregate 17 years after Brown v. Board of Education became law of the land. And what playwright Mark St. Germain paints quite vividly is the humanity behind the tough exteriors of activist Ann Atwater and Klansman C.P. Ellis.

If you were Bill Riddick, a young, educated and black federal mediator from the Department of Education facing a near-impossible task in a Southern town guaranteed to be hostile toward you, what would be your primary plan of attack? Riddick's idea was ingenious: You pull together the two most vocal leaders of the opposing factions and convert them to working together on the same team. Easy, it wasn't; Atwater and Ellis were longtime enemies.

But as St. Germain shows, a funny thing can happen when fiercely opposing sides realize they have more in common than they previously thought.

And that, quite frankly, is the beauty of St. Germain's script. Neither Atwater nor Ellis are saints in his play; both have flaws and painful histories. But more important is his revelation that both sides feared change, but for different reasons. For Ellis and the low-educated whites of Durham, federal mediators and the northern activists flooding into the South were seen as aggressors who wanted to destroy their way of life; and while the black community wanted equal education, they didn't necessarily want it sitting next to white kids.

History tells us desegregation prevailed, of course. Yet amid their volatile clash of personalities, St. Germain peels away decades worth of prejudice and hate and reveals very human truths about Atwater and Ellis – and by extension, us. And he skillfully reminds us that history is neither as black nor as white as it often seems (or is portrayed) to be.

But words alone do not a play make. Insightful direction is needed here, and it's provided by Dr. Arthur J. Beer, who gives life and power to St. Germain's script. With characters who are far-more complicated than the audience initially realizes, Beer carefully uses the beats of the story to shred the stereotypes of the angry black woman and the racist redneck to give us people we can relate to – even identify with and care about.

Even the show's technical wizardry serves the script well. With scenic and costume designer Melinda Pacha and lighting designer and technical director Alan Devlin, Beer places the action on a mostly bare stage – but that stage is rather deceitful. Upon entry into the theater, one sees only a brown, wood-paneled wall on stage. In the center of the wall is a large screen that comes to life a few minutes prior to the start of the show with a slideshow that helps set the tone of the show with photos of the era. (Never seen a Klan meeting before? Or a "coloreds only" waiting room or restaurant? You will here!) Then, throughout the show, the projections set each scene, which keeps the production running smoothly while tables and chairs are quickly exchanged.

But the highlights of the show are the three longtime pros and one relative newcomer who take the written word of their characters and find much to bring them to life.

The "youngster" in the group, Dan Johnson, fully captures what Atwater sees as Riddick's arrogance. And a transition toward the end of show is well executed and fully believable.

Recent Wilde Award winner Linda Rabin Hammell tackles a role that would be easy to either overplay (shrew) or underplay (doormat) – that of Mary Ellis, C.P.'s wife. Mary's character helps shed light on her husband, but she also serves to represent the townspeople, many of whom might be ready to embrace change. And – like always – Hammell nails it with a nuanced performance that finds all the correct emotional beats handed her by the playwright.

Ultimately, the show's success rests on the believability of the actors who play Atwater and Ellis. We must buy into the stereotypes before they can be destroyed – and both Madelyn Porter and Greg Trzaskoma work hard to make that happen. And they succeed!

Trzaskoma's Ellis certainly looks like the stereotypical redneck Klansman – a bit disheveled, a protruding belly, and a vocabulary rich with the now-infamous "n-word." He's loud and abrasive – and he's used to being a powerful man respected by many and feared by others. But as his status, livelihood and home life change, Trzaskoma applies every "trick" of his craft to show us the ongoing toll it takes on Ellis through the use of gestures, stature and vocal techniques – some of which are ever-so-slight and tough to perceive. (Maybe it was just me sitting off to the side a bit, but I lost some of his early dialogue because of the thick accent. But that stopped not long into the play.)

Porter's appearance is especially notable. One of the gems of the Detroit theater community – and someone whose work I've regretted missing in recent times – Porter is highly skilled at discovering the heart of even the toughest character, imbuing them with humor and passion that many others would ignore or fail to find. That's especially important in a production such as this, given the seriousness of the highly volatile situation in which Atwater finds herself and the tightrope one walks when discussing issues of race in a mixed audience of differing viewpoints. Porter instinctively knows when to allow us to laugh (and when not to), which helps the audience relax and breathe when other emotions might otherwise come into play. And her facial expressions alone are worth the price of admission.

Important plays are rare; so too are important plays about race and racism that don't have an agenda that overtly (or even covertly) take one side's position over another. While St. Germain's script and Beer's production tackle head on the troubling topics of race and racism in America and frame them within the context of an historical event, both focus on our shared humanity and a desire for a better life rather than any particular political position or dogma. Sometimes the least-known incidents of history can be its best teacher.

REVIEW:

'The Best of Enemies'

UDM Theatre Company

At Marygrove Theatre

8425 McNichols Road, Detroit

8 p.m. Friday, Oct. 3

8 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 4

2 p.m. Sunday, Oct. 5.

Contains adult and potentially offensive language

$5-20

313-993-3270

http://theatre.udmercy.edu