Plant Daddies Everywhere: A Look Inside the Men Who Father Their Foliage

We aren't gonna beat around the bush here

I can't help but notice that Grindr is full of hungry creatures, reaching out to take whatever you can give. They're insatiable.

I'm talking about plants, to be clear. My Grindr grid is covered in plants: Monstera in the back of a butt pic; pothos

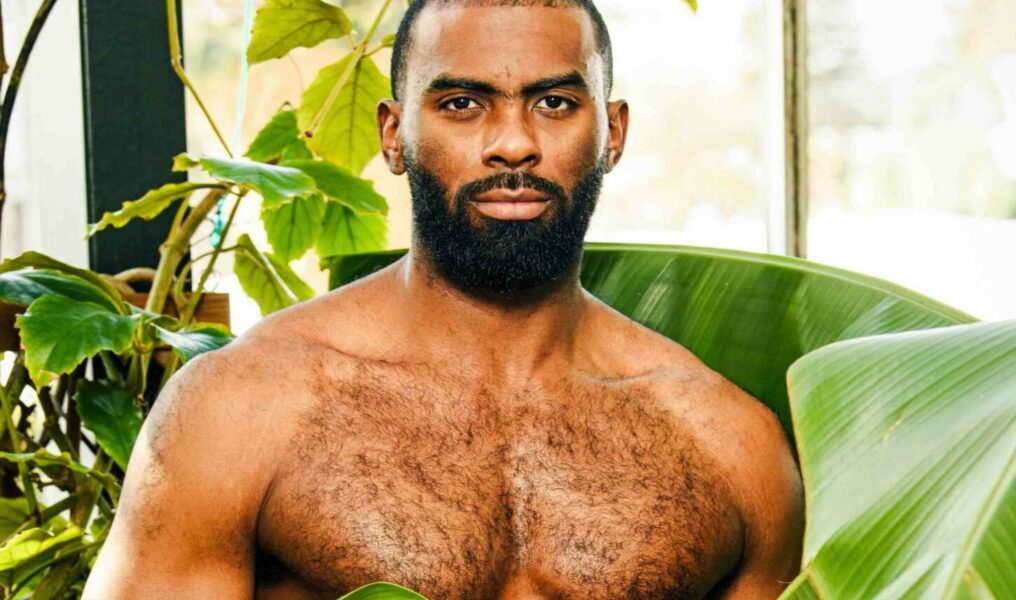

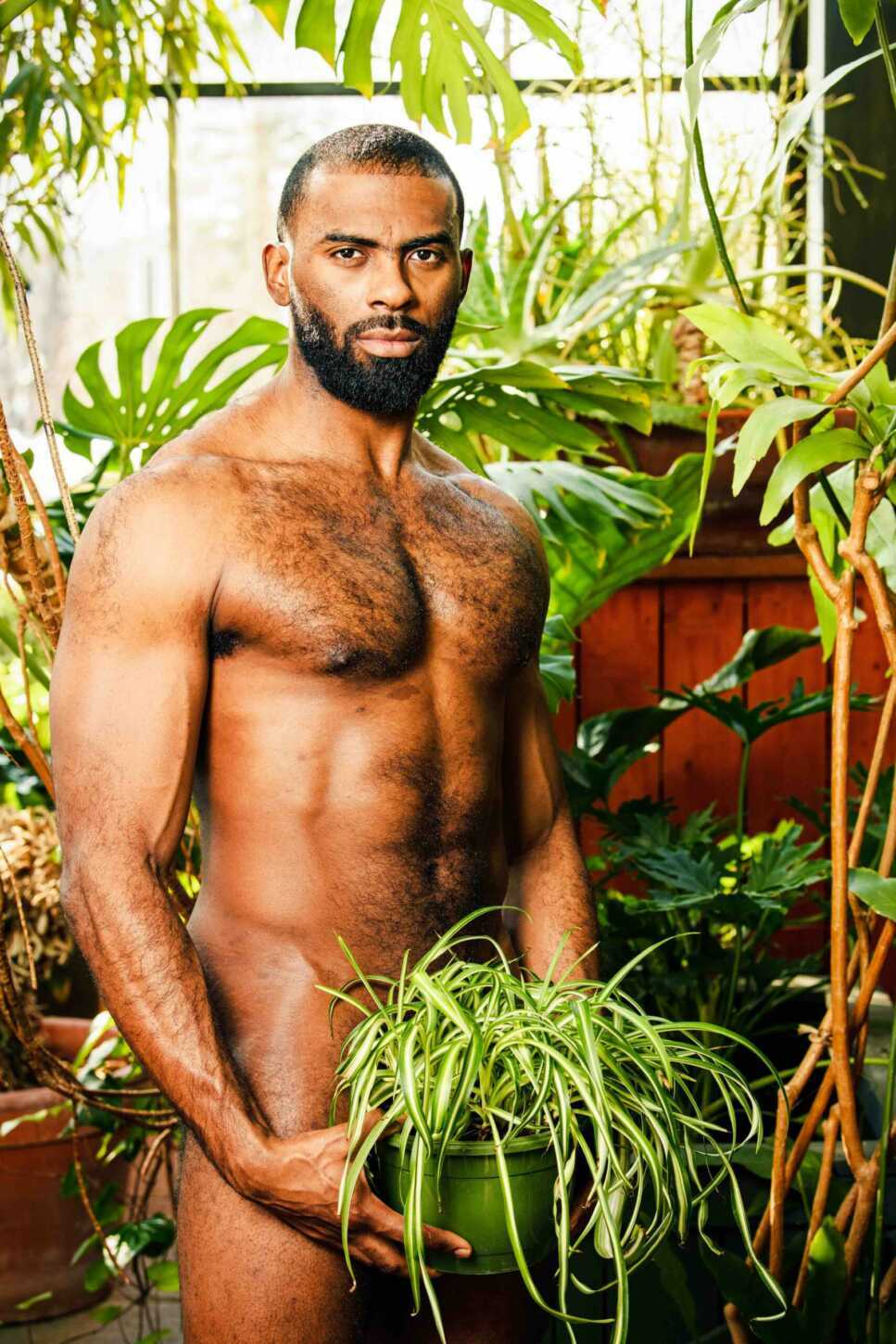

hanging out in a mirror selfie — the classic kind with a peace sign and a tongue stuck out. A few users come direct with screen names like "Plant Daddy." Plants, and especially house plants, are near or at the peak of fashion. Instagram accounts like @boyswithplants collect images of people posing charmingly, seductively, plants proudly on display. So it's no surprise that they're showing up in the spots where we find friendship, romance, or ahem.

But what does it mean when someone calls themselves a "plant daddy"? Do plants in a pic mean the user behind the screen is the image of zen and mindfulness? Or is it just an aesthetic thing? I spoke with a number of Grindr users, as well as some local friends who are on the apps and in the plant shops, to get some insight. As the social media cliché goes: It's complicated.

I messaged a number of Grindr users across Michigan with the decidedly unsexy line, "I'm writing a story about plants on Grindr and I see some plants in your profile photos. Can I ask you a few questions?" Most respondents admitted that they hadn't really noticed or thought about the plants I was seeing. Maybe the spider plant at the front of their photo was just there because it's a spot that gets good light — good for plants and selfies alike. Maybe they took the photo at a friend's house, never even noticed the plant in the first place.

In 1998, botanists James Wandersee and Elisabeth Schussler coined the term "plant blindness" to describe this phenomenon. It's a kind of inattention — like when you drive to the grocery store but upon arrival can't remember the trip. Some part of your mind was aware of the trip, but those memories are no longer conscious. Likewise, you might physically see a plant in a room but you may not actually notice it. In Western culture, plants are often backdrops and rarely the main event. We're acculturated to treat plants like wallpaper.

Consider anonymous Grindr profiles with profile pictures like these:

A user might choose these photos because they don't show anybody in particular. Maybe they indicate where the user went on vacation, or what kinds of weather they like, but they don't show the face of the human operating the account. For many people, some plants are nobody. You can contrast this to photos showing a dog or a cat, which might signal that the human in the shot is a “dog person” or a “cat person.” A profile picture of a tree doesn't make you a “tree person,” though.

For Grindr users who did notice the plants in their photos, the presence of plants could still be accidental. One user told me they just had too many plants to possibly take a picture in their apartment without a few green encroachments. For another user in Ann Arbor, the presence of plants coincides with their love of hiking. Plants are part of their outdoorsy nature, which a photo of them standing surrounded by sunflowers or drying wheat conveys. Plants don't always mean “nature,” though. One profile picture showed racks of cut plants drying upside-down. Naively, I thought they were garden herbs. I asked the user about his photo. He runs a commercial marijuana business and is, essentially, advertising his wares.

Others find botanical connection on Grindr. One couple in Detroit, with more than 100 plants in their apartment, told me that they've networked with other plant collectors via the app. They've even met up and exchanged plant cuttings. If you didn't know, many plants can be grown by taking a living stem from the plant and placing it in moist soil. It doesn't work with every plant, but it can be an easy way to gift someone a plant without giving up your own.

Philosopher Michael Marder, who I spoke to for this essay, reminded me that plants often blur the boundaries between "the many and the one, life and death, the inside and the outside[...]" What seems like one plant can be turned into two. In response, two (or more) people who seem wholly separate might come together. Is that what's going on with the plant swappers in Detroit? I don't know. They didn't confide; I didn't pry. Leave something to the imagination.

For some, plants might signal safety or good behavior. One friend I spoke to opined that potential hookups might see plants in his Grindr pics and infer that he's a safe person to be around. Plants in this case are a stand-in for being caring or generally safe company. Maybe the plants don't signal "hot sex," but they also do not signal "axe murderer."

Another friend confided that after he gave up certain oral pleasures, he found himself collecting cactuses. Here were literal reminders of what he wasn't allowing himself. They were also reminders he had to keep alive — just like he kept that promise to himself alive. It was a replacement activity of sorts and he'd made those strong, proud columns much more daunting, more forbidding. Plants, after all, aren't always safe. Consider the Venus fly trap (Dionaea muscipula) which attracts insects into its “mouth” (actually leaves) scent and color. Some Euphorbias, a favorite houseplant of many, contain a milky sap which can cause blistering, vomiting or even temporary blindness. Then, there's the matter of how plants interact with one another. The black walnut (Juglans nigra) and tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) are just two species who practice allelopathy (literally "mutual suffering") — the secretion of soil chemicals to inhibit the growth of other plants around them, literally trying to starve out the competition.

All those plants in our profile photos can be taken as a sign that other things are going on. As Marder reminded me, "Plants can change sexes from season to season… they can engage in sexual foreplay with pollinating insects, seducing with their shapes, colors and aromas." What's surrounding us in our profile pics isn't a cadre of green, chaste tchotchkes. It's a bacchanal, and it has scandalized the world before.

In turn-of-the-century Germany, schools banned botany instruction for fear that children would be made aware of "so-called bisexual plants." According to Dr. Joela Jacobs, associate professor of German Studies at the University of Arizona, this coincided with the new discipline of sexology and the coining of the term "homosexuality." Plants, which unashamedly toss their genetic material up into the air over anyone who passes by (think tree pollen and dandelion seeds!), were part of the devious bits of nature from which children should be protected. Plants, especially flowers, meant something in particular. Victorians even had “flower language.” If a gentleman expressed interest in you, but your affections lay elsewhere, you might send him a yellow carnation as a gentle brush-off. The code was a nice idea, but as Dr. Jacobs explains, "It never actually worked because there were so many disparate codebooks." The meaning of plants is bold, if ambiguous.

After several days of Grindr chats about plants, I thought I knew what to expect. Then, I messaged a self-declared "Plant Daddy." He told me he grows plants commercially for landscaping. Then he told me about his other grower. Then he sent me a bunch of photos I didn't ask to see. When it took me a few minutes to reply, he began sending additional messages asking where I'd gone. I hadn't gone anywhere. I was just moving slowly.

I realized that this was probably how he messages everyone. I was as un-special as one of a million tulip bulbs he might plant. Not long after, someone reported my account for impersonation. I'd created a second Grindr account so that my plant chats could be separate from my personal DMs. Some plants, like aspen trees, are so good at cloning that what looks like a whole forest can actually be just one plant joined underground by a massive root structure. Someone on Grindr didn't think two accounts that looked like me could be connected, though. I lost most of my plant chats. It all felt very seasonal.

Plants themselves don't use Grindr, but I like to imagine what that could be like. Maybe, like "Plant Daddy," they'd send rapid-fire demands. "U got water? Water? You got water? Looking for water." Maybe, like ephemeral flowers, a plant would log on for one hour a year and then delete its account. Or like invasive kudzu, one profile picture would slowly take over the entire grid as your dating selection was narrowed down to one intellect operating an ever-growing number of bodies. Don't report them for impersonation, though. They're just writing an article.